For those of us with New York FOMO (so many great exhibitions this month!) here’s Holland Cotter’s words on Agnes Martin’s retrospective at Guggenheim. For anyone who has a friend or relative who “doesn’t get” abstract painting, send them here. Read Cotter in partial below, in full via New York Times.

To be honest, I wonder what a lot of people see in abstract painting. I love it, the idea of it and the experience of it, because it’s been in my life for decades. But what if you don’t have that information? How do you approach an art empty of figures and evident narratives? How do you find out what, if anything, is in it for you? What do you do to make it your own?

“You go there and sit and look.”

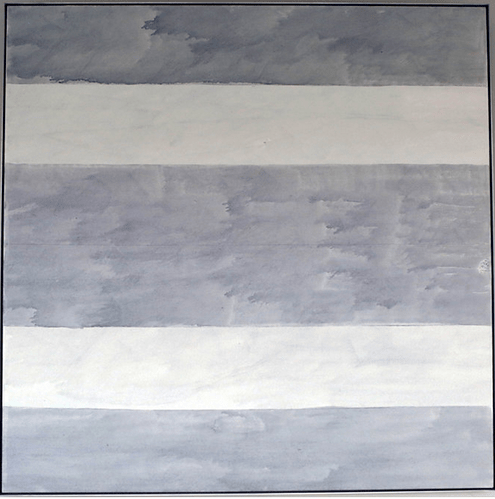

That was the terse advice that the painter Agnes Martin gave to anyone coming to her paintings, more than 100 of which are now floating up the ramps of the Guggenheim Museum rotunda in the most out-of-this-world-beautiful retrospective I’ve seen in this space in years. Her art is as abstract as abstract gets, yet her presence in it is palpable. So is her story, once you know how to read it.

Martin, who died in 2004, was right about learning by sitting and looking, though, in the case of her work, standing is even better, because you can move around and take it in from different perspectives. View her paintings from several feet away, and their surfaces — whitish, pinkish, grayish, brownish — look hazily blank, as if they needed a dusting or a buffing. Move closer, and complicated, eye-tricking, self-erasing textures come in and out of focus. Move in very close, and you find that the surfaces are marked with hand-drawn lines, often faint but always firm, and regularly spaced, like the lines of a musical staff, or an accounting ledger, or a school notebook.

These are the basic elements of Martin’s art, and it took time, about 45 years, for her to find and refine them. She was born in 1912 in rural Saskatchewan, Canada (“the land of no opportunity,” she called it). Her father, a wheat farmer, died when she was 2. Her mother, harsh but resourceful, supported the family, though, by Martin’s account, it was her maternal grandfather who gave her a childhood. A gentle Calvinist, he read inspirational books to her, among them “The Pilgrim’s Progress.” Its tale of determination, despondency and hard-won reward set her path.

The path, which took her away from home early, was peppered with byways, detours and emergency stops. Martin once wrote, in her Palmer-method cursive, a long list of jobs she’d worked since her youth, among them playground director, tennis coach, baker’s helper, ice cream packer, receptionist, janitor, dishwasher (three times), waitress (many times), warden to “criminal boys,” and manager of “five Hindus baling hay.” Somewhere in the summing-up there is, no doubt, a mention of art instructor, because that’s what she studied to be in 1941 at Teachers College, Columbia University, in New York City. A year later, at 30, she decided not just to teach art, but also to make it, to be an artist.

*Image: An untitled work from 2004 from Agnes Martin. Credit 2016 Agnes Martin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Hiroko Masuike/The New York Times