In honor of Prince’s untimely passing, here’s the one and only Hilton Als on Prince and black queer sexuality. Originally published in 2012, the whole, very entertaining read is available via Harper’s archive, with an excerpt below.

Being enthralled—or, more accurately, frightened and turned on by Prince and what his various looks said about an aspect of black male sexuality—was that something only comedians could talk about? And when they did, did Prince’s weirdness have to be the butt of the joke, so to speak, along with colored queerness? For the most part, I wasn’t interested in the Prince who produced 1999 and Purple Rain and Around the World in a Day and at least half of Sign “O” the Times (all released between 1982 and 1987). Those felt like self-consciously “white” pop albums to me, a craven desire on The Artist’s part to belong to the world outside the colored queens I had known growing up, who called Prince “Miss.” Why did he want to leave us for that non-world of convention he seemed to aspire to, where “she” got married to a woman who looked like her, then, to make matters worse, dressed as Miles Davis had while on tour promoting his rock-jazz fusion album Bitches Brew? Why did he want to betray the colored queer in himself?

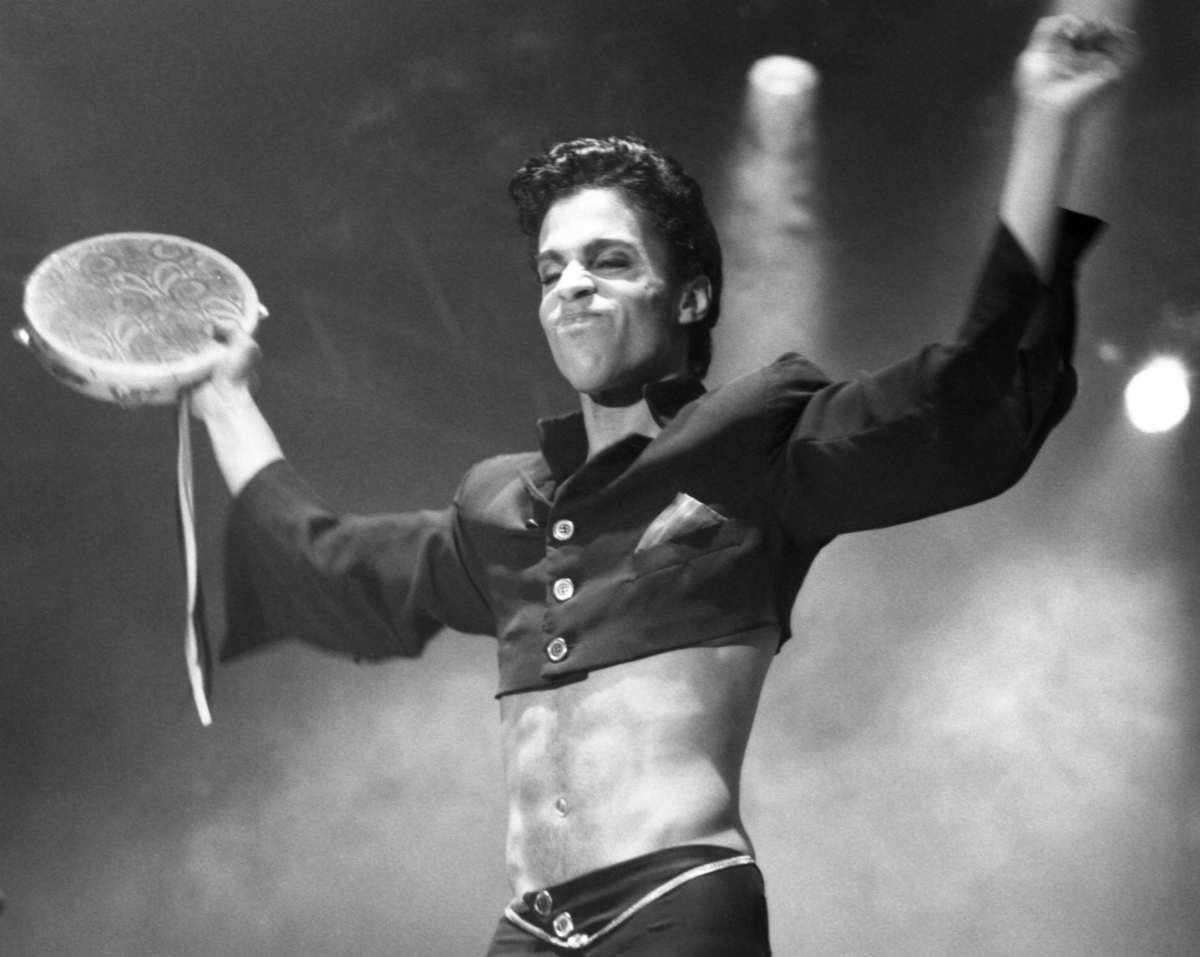

At parties in New York, uptown and down, I stopped dancing when white frat boys pumped their fists in the air to “1999,” or slid across the floor when “Kiss” came on, or grabbed their obliging girlfriends—girls unlike the fierce dykes who sang and played backup for Prince in his early years—and twirled them around to “Raspberry Beret.” They didn’t know what he meant by any of it, and I did, but I no longer mattered; what mattered was Prince’s acquisition of a larger audience, those people who purchased records and filled concert halls, not the black queens who lip-synched to “Sister” while voguing near the Hudson River in the clear light of night. But in 1988, Prince redeemed himself—somewhat. That year, he released Lovesexy. It was as if Lazarus had risen from some strange frat-boy-populated cave. The cover told us everything: it was Prince, naked, his hair feathered. The album featured another female doppelgänger—Cat, a dancer and singer who looked like Prince insofar as anyone could look like Prince. She was spectacular in ways that Prince had toned down by then. You could see it in the music videos. He performed, but Cat worked. But he was still too much the showman and the Boss Man not to upstage her.

Cat was beautiful. She had a big ass. She posed on the Thunderbird that Prince and his cohort partied on at the end of the show. With her long, curly hair and well-toned biceps, Cat was the girl Prince had been before he stopped being a girl: outrageous and demanding. She rapped to the audience. She got right in our collective face; you could see her eyeliner. Prince smiled behind his guitar, behind his own shimmering ass as Cat became him and sang his lyrics: a twinning for the ages. Cat was not only Prince, she was Cynthia and Rosie from Sly’s Family Stone, Betty Davis without Miles. I longed for that twinning. I longed to be the Prince to someone’s Cat, and the other way around, too. Like a figure in a Platonic dialogue, I had always longed to meet my other half, my Prince half. If Prince had his twin, why couldn’t I? But twinship did not come easily. In time I would find my Prince, but when I did it was complicated. He wanted Dorothy Parker, and I was not Dorothy Parker.

*Image of Prince via Huffington Post