In the LA Review of Books, Melissa Dinsman talks to Franco Moretti about what exactly the “digital humanities”—a sprawling assemblage of tools and approaches, reviled by some and lauded by others—is. Moretti begins by pointing out the inadequacy of the very term “digital humanities.” An excerpt:

At this point in your career, how would you describe the role that the digital plays in your work? You’ve used the phrase “digital humanities.” Do you think of your work as part of the digital humanities or is it something much larger?

No. First of all the term “digital humanities” means nothing. Computational criticism has more meaning, but now we all use the term “digital humanities” — me included. I would say that DH occupies about 50 percent of my work. You can’t possibly know this, but when my last two books were going to be published — Distant Reading and The Bourgeois — I convinced my publisher (and it took some convincing) to have them come out on the same day because they were for me two sides of the coin of the work I tried to do. And what I find potentially interesting is that the two sides don’t add up to a whole. I do things in the mode of Distant Reading that I could never do in the mode of The Bourgeois. But it also works the other way around. When I write a book with zero digital humanities content, or very little, like The Bourgeois, I find myself doing things that I cannot do with the other approach. Exactly what things are available in the one and in the other and are they mutually exclusive, I still haven’t figured out how to think about this. But for me, this is going to be the problem for the years to come because I don’t want to give up any of these two realities. They are equally dear to me.

So there hasn’t been a sort of natural blending then into some sort of whole. It is still very much separate.

It is. I am loosely planning a book on tragic form, which occasionally I try to conceive as a unification of the two. Who knows. This is planning. It is easy to plan. Doing is a different thing.

Are there any digital or media subfields in particular that you think yield the most benefit to the humanities and why?

I don’t see a special area. What I would be very interested in reflecting upon is the different fates, the different destinies, so far of the digital approach in literature, history, and art history, because DH has clearly functioned very differently in those three fields. And why has it functioned so differently? Many of your questions have to do with the humanities in general and this would be an interesting way to try to figure out why this DH approach is much more productive in literature than in the two other cases. Not that we’ve done anything earth-shattering, but it’s clear that English departments have done more than the others in this field. In fact, as you know, I am currently in Switzerland, and there are several universities here that are beginning to think in these terms by organizing discussions between historians, literary critics, and art historians. I think this kind of enlarging of the panorama will be more fruitful, rather than splitting hairs within the literary digital humanities. We need it. It’s a little claustrophobic in our field.

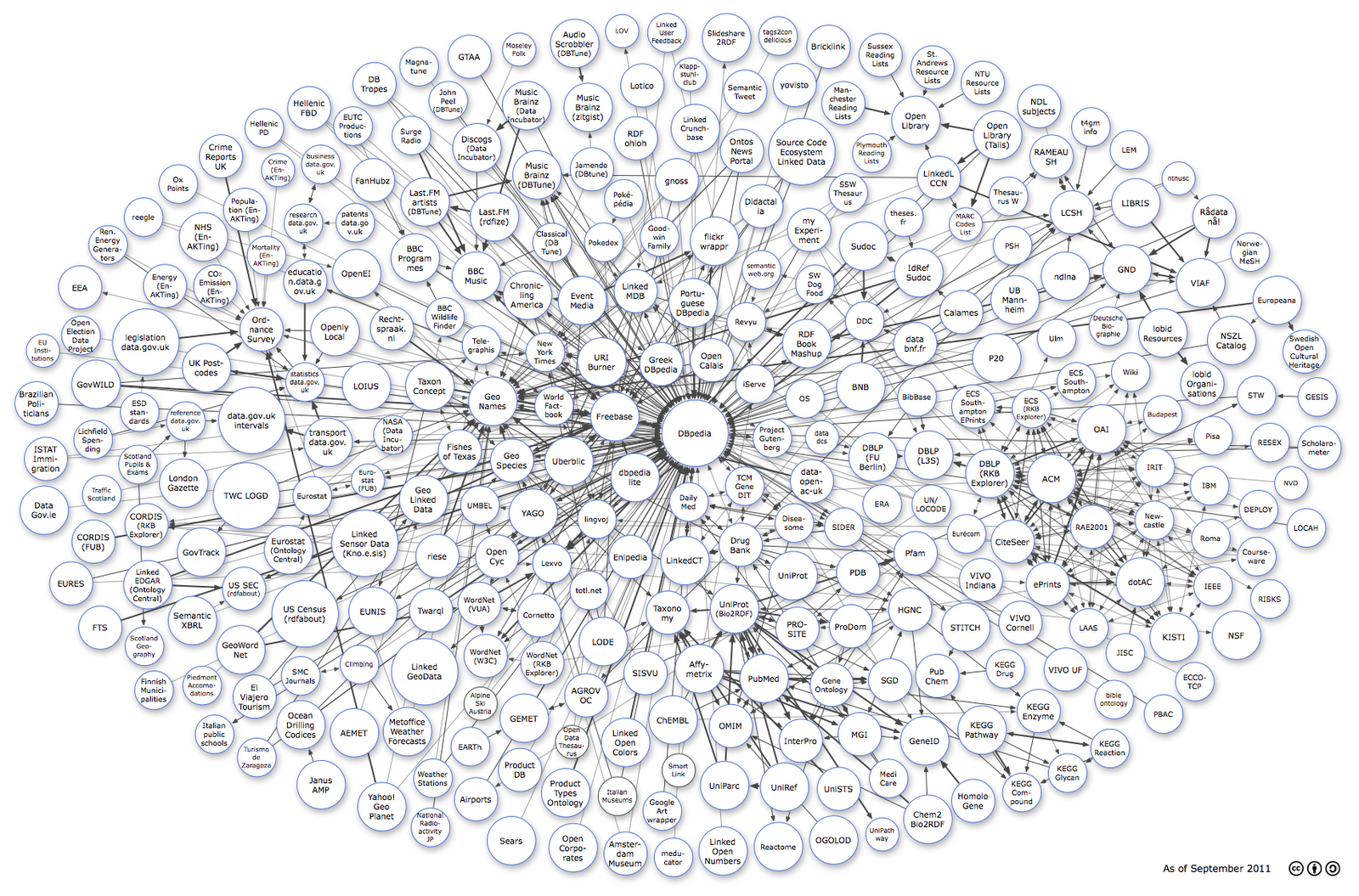

Image: “Linking Open Data” cloud diagram. Via digitalmiscellaniesindex.blogspot.com.