For the Nation, Eric Foner writes about American radicalism, teaching its rich history as a professor at Columbia University, and the change in belief in radical politics among generations. Read Foner in partial below, in full via the Nation.

Last spring, I taught my final class at Columbia University, and now I’m riding off into the sunset of retirement. The course, which attracted some 180 students, was called “The American Radical Tradition.” Beginning with the American Revolution, it explored the ideas, tactics, strengths, weaknesses, and interconnections of the movements that have attempted to change American society—from abolitionism and feminism to the labor movement, socialism, communism, black radicalism, the New Left, Occupy Wall Street, and Black Lives Matter. Although the word “radicalism” is often applied to those on the right as well as the left, I announced at the outset that since we had only one semester, I planned to focus on what might be called left-wing radicalism. Those students who wanted exposure to right-wing radicalism, I added, could enroll in any class in Columbia’s business school.

Teaching the class as Barack Obama’s presidency neared its end and Senator Bernie Sanders’s campaign ignited the enthusiasm of millennials was an interesting experience. I began with the premise that radicalism has been a persistent feature of our history and that radicals, while often castigated as foreign-inspired enemies of American institutions, have usually sprung from our culture, spoken its language, and appealed to some of our deepest values—facts that help to explain radicalism’s persistence even in the face of tenacious opposition. American radicalism entails a visionary aspiration to remake the world on the basis of greater equality—economic, legal, social, racial, or sexual. Despite the occasional resort to violence, most of these movements have reflected the democratic ethos of American life: They’ve been open rather than secretive and have relied on education, example, or political action rather than coercion. Not surprisingly, they have also reflected some of the larger society’s flaws; radicals are a product of their society, no matter how fully they reject certain aspects of it. While I made clear my sympathy with most of the groups we studied, I also insisted that we should not be surprised that some abolitionists were antifeminist, some feminists racist, some labor organizations hostile to immigrants. Neither history nor politics is well served by simple hagiography.

From Thomas Paine’s ideal of an America freed from the hereditary inequalities of Europe, to the vision of liberation from legal and customary bondage espoused by abolitionists and feminists; from the Knights of Labor’s concept of a cooperative commonwealth, to the socialists’ call for workers to organize society in accordance with their own aspirations; from the New Left’s embrace of personal liberation as a goal every bit as worthy as material abundance, to the current efforts to counteract the less appealing consequences of globalization, each generation has made its distinctive contribution to an ongoing radical tradition. Many achievements that we think of as the most admirable in our history are to a considerable extent the outgrowth of American radicalism, including the abolition of slavery, the dramatic expansion of women’s rights, the respect for civil liberties and our right of dissent, and the efforts today to tame a rampant capitalism and combat economic inequality. Many of our current ideas about freedom, equality, and the rights of citizens originated with American radicals.

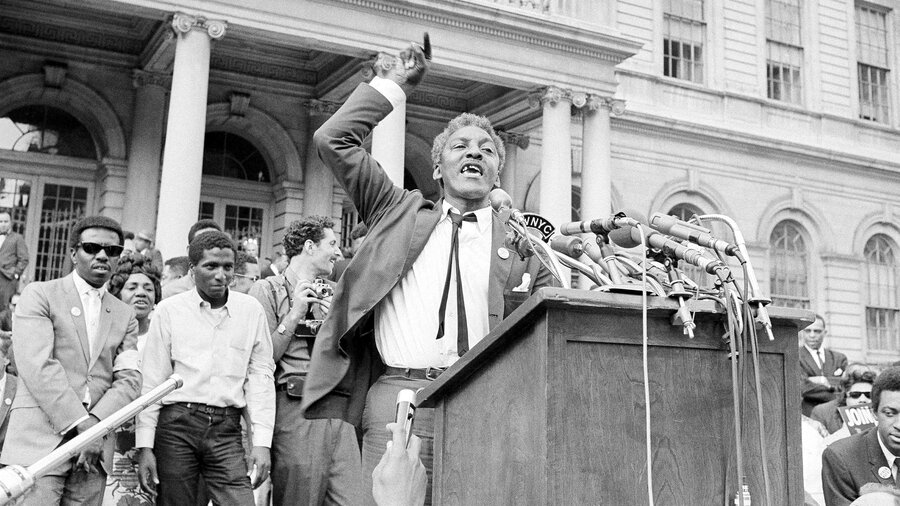

*Image of Bayard Rustin via NPR