For Sloan Science & Film, Sonia Epistein interviews Whitney curator Chrissie Iles, who is hard at work on the upcoming survey Dreamlands. The exhibition will look at a history of experimental film from 1905 to today, with artists ranging from Oskar Schlemmer and Walt Disney to Lynn Hershman Leeson and Dora Budor. Read Iles in conversation with Epstein below, or in full via Sloan.

Science & Film: In researching a show that is a chronicle of motion pictures which spans 1905 to 2016, are movies are dead?

Chrissie Iles: I don’t think movies are dead. Whenever I make an exhibition it is because there feels an urgent need to do so. In this case, I was responding to a sea change that has clearly been occurring in the moving image, and its presence in digital, immersive space. Artists and filmmakers are articulating something dramatically new, using new developments in technology, from virtual reality and 360 degree cameras to 3D and the way in which 3D printing is changing our understanding of material objects. This is profoundly shifting the relationship between technology and the human body, and science fiction, which always operates as a bridge between the present and the future, has become newly important. I spent a lot of time listening to young artists and looking at their work, and it became clear that certain moments in art and film history grappled with similar ideas that have a strong relationship to what is going on now. It became evident to me that the kinds of issues that are being explored now by artists were present in the culture of Weimar Germany in the 1920s. In contrast to France, where experiments with the cinematic were shaped by a dialogue with Surrealism and literature, in Germany, artists were influenced by the Bauhaus and the new industrialized environment, and their work engaged with abstraction, color, light, the cyborg, and technology’s relationship to the body in the spectacular immersive space of the city.

Germany at that point was the most industrialized country in Europe, and the closest to the United States in its urban modernity. The experimentation with abstract film by German artists was also connected to the avant-garde ideas that had emerged during the Russian Revolution. [Kazimir] Malevich attempted to make a film in collaboration with [Hans] Richter, but for various practical and political reasons, it was not realized. In Berlin, artists were exploring the limits of the film frame and optical perception, the impact of technology on the body, using rhythm, mechanical movement, and robotic forms, in film, theater, and also in collage, in the work of artists like Hannah Hoch. The aftermath of the First World War was significant; it had been the first modern war fought with technology, and in every city, including Berlin, was populated by its returning soldiers’ visibly traumatized, wounded bodies, held together with crudely made prosthetics. Bertolt Brecht, Erwin Piscator, and Bauhaus artists were experimenting with new ideas of theatrical space, defined through color, light and fluid architectural structures, creating new possibilities for an all-surrounding immersive projective space. The 1960s saw a resurfacing of this creative energy shut down by the Second World War. It was filtered through a collective processing of the war’s traumatic aftermath–a process intensified by the new traumas of the Vietnam War and the social and political upheavals of that period.

It seems to me that this current new generation of artists is moving that creative energy forward yet again, in a new way that, thanks to the recent radical developments in technology, has made a definitive break with the twentieth century. As a result, their creative approach is focused on the future in a way that resonates with the period of Weimar Berlin. This exhibition brings young artists into a dialogue with that history in a way that is new; their work is more often seen in the context of group surveys, and biennial and triennial exhibitions. The show also shifts the small group of works from the 1960s and 1970s, including Anthony McCall, Stan VanDerBeek, Jud Yalkut, and Bruce Conner, beyond their specific historical moment of expanded cinema, destruction in art, and Structuralist film, into a broader history of art and film.

S&F: And in relation to the technology the filmmakers use too, right?

CI: Yes. Their work can be understood here as part of a broader relationship to technology than simply that of the film apparatus. In making the connection between these different moments in art and film history, I decided to look at the whole century, and tease out some of the main strands that are present in the different decades, which seemed to pivot around immersive space and the relationship of technology to the body. The result is a group of immersive works that use the cinematic in different forms to explore ideas in ways that speak to each other across history.

One of the strands of the show is the cyborg and the cyborgian body, which first appeared in the work of artists such as Oskar Schlemmer. The first work in the show is a film reconstructing his THE TRIADIC BALLET from 1922, which was made in the 1960s in Germany. In that faithful reconstruction, you can really see the importance of the robotic body and the First World War (in which Schlemmer took part). The film sets the tone of the exhibition; color, light, music, an animation of line, the flattening of space, the body; immersion. Almost every piece of music in this show is non-diagetic, which underlines the emphasis on affect rather than narrative.

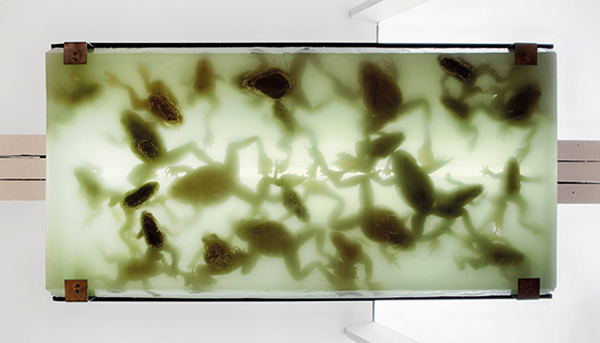

*Image of Dora Budor “Kata Doksa” (2014) via Sloan