In Mute magazine, Josephine Berry, a lecturer at Goldsmiths and an editor at Mute, reviews a new anthology that focuses on the history of London’s SPACE studios, which has worked to provide studios for artists in the capital for over fifty years. As Berry notes, Artists in the City: SPACE in ’68 and Beyond traces the evolution of SPACE as it negotiated the changing conditions for living and making art in a major urban center, from postwar deindustrialization to the rise of the neoliberal city. Today, when cities like London are more hostile than ever to DIY arts, it’s crucial to rethink the relationship between artists and the city, suggests Berry. Here’s an excerpt from her review:

A continuous thread drawn through the book is the consideration of collective endeavours and how, in the face of the art market’s hyper-individualism and capitalism’s creation of ubiquitous competition, conditions for artists, as for workers in general, can only be improved through collectively established strategies, infrastructures and standards able to reflect conditions and support the struggle for change. Anna Harding clearly understands SPACE as belonging to this wider ecology of organising, yet as with other commissioning decisions, is also unafraid to show its limits and question its future. There is much focus on SPACE’s other sister organisation AIR (Art Information Registry), a documentation registry and information network established by Sedgley in 1967 and intended to democratise art by connecting it directly to its publics and collectors, removing the need for the gallery. Another focus is on the first Artists’ Union (1972-83), and its inspiration for the recent Artists’ Union England (AUE) established in 2014 and still running. In her essay on these two artists’ unions, Ana Torok quotes AUE founder Katriona Beales’ retort to those who would disparage artists’ professionalisation, asserting that today, emerging artists ‘can’t afford to be unprofessional’. The thorny question of professionalisation and its risks (that, as was hotly debated throughout SPACE’s history, organisational power might end up in the hands of detached managers not practitioners) is elegantly dissected by one of the book’s closing essays on DIY by David Morris.

Morris acknowledges straight away that ‘a DIY ethic parallels “creative class” values of entrepreneurship, hyper-individualism, gentrification and advanced capital accumulation.’ Self-organisation and activation border on the entrepreneurial and DIY continuously risks dignifying the logic of human capital, but is also, he insists, ‘communal, utopian, modest, transformative.’ This wavering power hinges on the ‘it’ in DIY that, as Morris concludes, is always under construction and in motion: ‘its ‘it’ is an action that is collective and constructive […] the ‘it’ is in the doing. Do it!’ This sounds a lot like making art. Clasping these multiple strands of history, tactics and critique together, one might say that the book articulates artistic DIY as the dark side of neoliberalism’s self-exploitative moon, holding the power to sever the common association of entrepreneurialism and individualism. Amidst post-Fordism’s deliberate strategy of discontinuous change and generalised precarity, DIY’s own messy and precarious way of producing objects as an effect of actions can be a similarly agile and molecular counterforce. It also offers a way to think group efforts outside of the binaries of professional or hobbyist, individual artist or collectivised worker, expression or infrastructure. Artists in the City is a crucial manual for thinking through the (mess)thetic politics of systems, and the professional infrastructures of art. In this, it is able to dissolve the boundaries between art and organising and offer some hope for withstanding the devastation of neoliberal life and financialisation’s total commodification of space. If the Situationist dream of a hacienda made of glass briefly existed in Manchester thanks to the efforts of Tony Wilson, the future artistic struggle for the city must now entail dismantling the glass towers in which our financialised futures are stolen from us and stored up as value for speculators. DIY’s ‘it is in the doing’ keeps the future uncertain so as to return it into our hands, while improvising structures that temporarily withstand the overarching forces of expropriation. SPACE admirably embodies this dual power of organisation and inventive uncertainty. Long may it wobble!

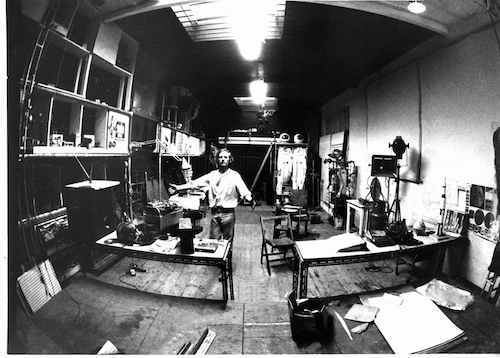

Image: Bruce Lacey in his studio at Martello Street, early ‘70s. Via Mute.