As a writer, John Lanchester is a rarity: he is a critically acclaimed novelist who also understands the nuances of economics and finance, as evidenced in his journalism and nonfiction books. (He united these seemingly divergent interests in his 2013 novel Capital.) Lanchester seems like the perfect person to confront the question of whether economics and the humanities can ever see eye to eye, as he does in this week’s issue of the New Yorker. After examining a trio of recent books that make a laudable attempt to bridge the divide between the two disciplines, Lanchester concludes that it simply can’t be done: “The project of reducing behavior to laws and the project of attending to human beings in all their complexity and specifics are diametrically opposed.” Here’s an excerpt from the piece:

Economics, Morson and Schapiro say, has three systematic biases: it ignores the role of culture, it ignores the fact that “to understand people one must tell stories about them,” and it constantly touches on ethical questions beyond its ken. Culture, stories, and ethics are things that can’t be reduced to equations, and economics accordingly has difficulty with them. Morson and Schapiro’s solution is to use the study of the humanities, and particularly of realist fiction, to broaden perspectives and to reintroduce to economics those three missing factors. Realist fiction, in their view, is the territory of the fox. It is, they argue, based on casuistry, which gets a bad rap but historically was the idea that the ethics of a situation are based on the specifics of the actual case. The authors’ hero is Tolstoy, who understood in his fiction that abstract principles should not triumph over human realities. It is an old idea in philosophy, clearly spelled out by Aristotle: “About some things it is not possible to make a universal statement which shall be correct.” The way to convey this truth is through the humanities, which, “properly taught”—an important part of their argument, since “Cents and Sensibility” has plenty to say about the defects of the contemporary curriculum—“offer an escape from the prison house of self and the limitations of time and place.”

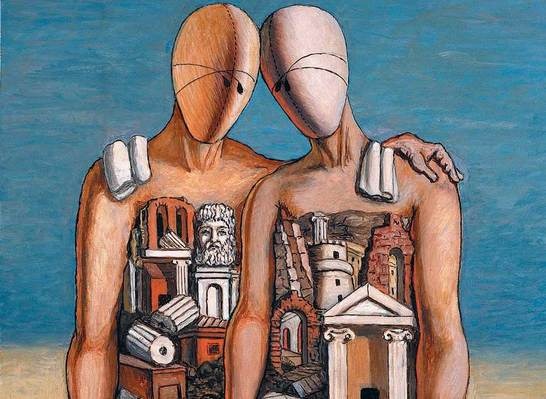

Image: Giorgio de Chirico, Two Archaeologists (detail).