Two years ago French multidisciplinary artist Camille Henrot shot from the art world’s margins to its pulsing centre. Artists envied, critics scrambled for interviews, and curators tussled to show ‘something; anything’. The reason? Henrot won the Silver Lion at the 2013 Venice Biennale for Grosse Fatigue (2013), an ambitious 13-minute video that retold several creation myths in an ecstatic, thrillingly exuberant burst of spoken word poetry and moving images in eye-watering HD.

But for all this, Grosse Fatigue displayed a troubling and dated tendency. It treated non-white bodies as anthropological curiosities, as examples of the exotic, otherworldly or primitive against which whiteness as rational, modern, cerebral and desirable could be constructed, measured and defined. What’s more, it wasn’t an isolated instance.

Last year at Tate Modern (Friday 28 February 2014) a selection of Henrot’s other video works were shown and a large proportion of them restaged this outmoded tendency to ‘other’. The Strife of Love in a Dream (2011) was a fevered depiction of seething Indian multitudes, collective ritual and magical performance that felt dangerously close to classic orientalism; Coupé / Décalé (2011) trained an anthropological (i.e. detached observer to specimen) gaze on a land diving ceremony in the South Pacific republic of Vanuatu; and Cynopolis (2009) focused on dogs scavenging around a pyramid in Sakkara, Egypt.

While the gloss of critical awareness (on the part of Henrot) and the activation of spectatorial critical distance were submitted as, respectively, the get-out clause for post colonial critique and the motive for the production of each work, the spectre of an anachronistic exoticism still loomed large.

Earlier that evening Tate announced plans to revisit Jean-Hubert Martin’s landmark, 1989 group show ‘Magiciens de la Terre’, to ‘reconsider’ the exhibition and its now dated position of exoticising non-Western artists and individuals. So in the Q&A that followed, I asked Henrot about her tendency to exoticise and preserve the other as other: was it evidence of the endurance of Martin’s folly in the twenty first century? Was it something she was uncomfortable with?

Henrot answered she was aware of exoticisation in her work, but strove to tackle and deal with it head on, not shy away. I wasn’t convinced that was happening on screen, but didn’t press the issue. Now, in spectacular style, Henrot seems to be at it again.

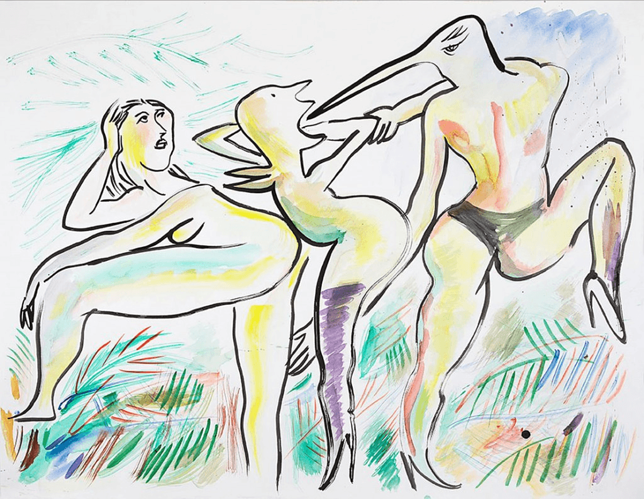

In last week’s UK Guardian online, the artist displayed a staggering level of sociocultural dilettantism in a bizarrely gushing article titled ‘Nicki Minaj becomes a feminist art muse’. In the short piece written by journalist Aindrea Emelife, covering a collection of Henrot drawings executed in naïve style (2015 work My Anaconda Don’t pictured above) and inspired by Minaj’s highly sexualised Anaconda music video, Henrot praised the musician as ‘a feminist icon’ who is ‘challenging us to embrace our primal nature’ (my emphasis throughout). Treating Minaj as readymade and performing an exercise that is the polar opposite of détournement (that is elevating culture industry product to the level of multidimensional and oblique critique) Henrot claimed:

‘She is deliberately likening herself to a Barbie, and [referencing] the fastidiousness of being plastic and fake. She’s making herself a caricature of what people want her to be’

For Henrot, then, Minaj is a covert accelerationist, while the Anaconda video:

‘Seems more like a statement on forgetting stereotypes and embracing yourself. It is vulgar, it is beautiful’

But isn’t the objectification of black female bodies, reduced to the abstract physiological markers of breast and bum, a centuries old device of dehumanisation enacted by what bell hooks calls ‘white supremacist patriarchy’? And wasn’t the director – i.e. the person who conceptualised, pitched, shot and oversaw the edit – of Anaconda a white male named Colin Tilley? Of course Tilley’s not a white supremacist, but Henrot’s astonishing lack of awareness is embarrassingly foregrounded by the fact she doesn’t know the person responsible for, as she puts it, ‘abus[ing] the typical “black music-video girl” archetype to the very end’ is a man.

‘I like to think [Minaj] created Anaconda to evoke criticism…and create hate’ says Henrot ‘if only so we too can realize our aversion to the sexualisation of women’.

Really? Did it create hate? Mostly people seemed disappointed; disappointed a truly innovative and at times frighteningly intense artist had seemingly exchanged the experimentation and eccentric schizophrenia of tracks like ‘Stupid Hoe’, for tepid, deconstructed Miami bass, featuring Sir-Mix-a-Lot harping on about how his soft penis (the titular anaconda) won’t get hard unless a woman has a large ass.

But the issue here isn’t Minaj, it’s Henrot: Henrot speaking for and denying the agency of another artist; Henrot pontificating; Henrot exoticising; Henrot doing the same patronizing veneration of ‘primitive’ culture that modernists like Picasso performed, especially when she declares Minaj is ‘a shaman’ who is ‘portraying the sexuality of women, the wild woman’.

The question is: are statements of ‘positive primitivism’ and the superimposition of a shoddy feminist agenda, okay if it’s simply an artist talking about and taking ownership of a live human being as ‘muse’? What do you think?

Is Camille Henrot essentialising like its 1989?

Is she appropriating Minaj to articulate her own normative and rather basic ‘ideas about sexuality’?

Is there such a thing as positive primitivism?

Are you excited by Henrot’s new drawings, or should she stick to videos and Ikebana?

Did you like Grosse Fatigue?