At Viewpoint magazine, education scholars David I. Backer and Kate Cairns argue that the history of “critical pedagogy” offers lessons for overcoming the division between class and identity that often hampers movement-building on the left. They write that in its richest form, critical pedagogy can bridge the gap between the universality of class and the “positionality” of racial, gender, and national identity. Here’s an excerpt from the piece:

None of this is new. Others have written eloquently about difference, solidarity, and collective action. Some have engaged in insightful analysis of the supposed class/identity impasse. We want to intervene here by challenging the framing of this dichotomy; rather than take one side or the other, we see the impasse as the figment of a certain imagined relation to the current political landscape. As education researchers and activists frustrated by the terms of this imagined relation both in writing and in movement spaces, we have a different imagined relation, another ideology where this impasse doesn’t appear. Thinking about organizing pedagogically – centering the material conditions of activism, or the ritual practices involved in trying to change relations of production – gets us to this other ideology.

Put differently, if we think pedagogically about the impasse threatening the left there is no impasse at all.

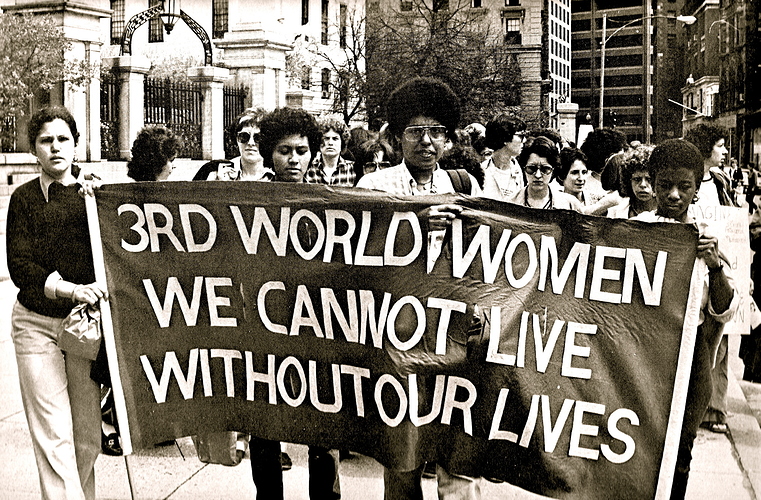

Our approach reinvigorates and builds upon a conception of identity politics rooted in a critique of structural oppression. Salar Mohandesi notes that much contemporary rhetoric on identity politics lacks the structural critique that was so central to its history in radical social movements. As a result, he argues that “identity politics has now increasingly become an obstacle to unity.” Beyond an individualistic project of listing personal privileges and disadvantages, we see the politics of identity as one of positionality: a recognition of our different locations within intersecting systems of oppression, including capitalism, patriarchy and white supremacy. This critique was forcefully made by black feminists in the Combahee River Collective, who challenged a universalist vision of socialism that denied racial, gendered, and sexual injustice. Their 1977 statement called on organizers to “articulate the real class situation of persons who are not merely raceless, sexless, workers, but for whom racial and sexual oppression are significant determinants of their working/economic lives.” Without addressing these processes, we risk reproducing these injustices in our movements.

Image: The Combahee River Collective, 1979. Via the Verso blog.