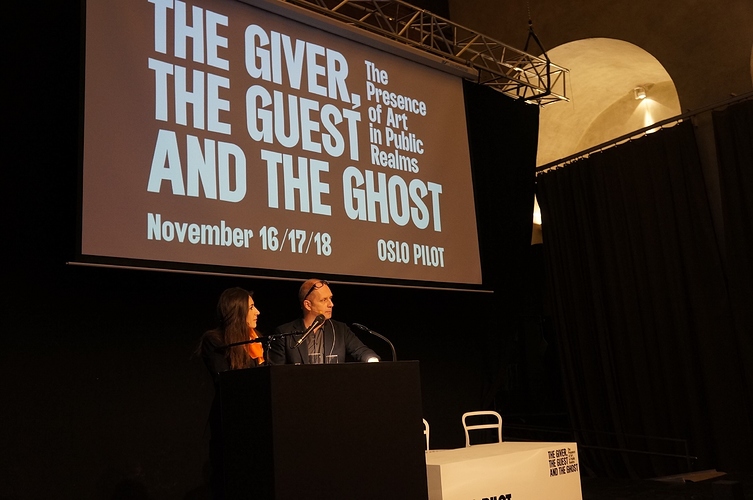

Foto: Ane Mari Aakernes. Symposium The Giver, the Guest and the Ghost: The Presence of Art in Public Realms. General views, OSLO PILOT, 2016, Oslo

Text by Arielle Bier

When city development booms at exhaustive rates, can we rely on art to slow society back down into a digestible time-scale? In recent years, the Norwegian capital of Oslo has consistently topped the charts as one of the fastest growing cities in Europe and the rapid changes citizens face are only starting to emerge. Bearing this in mind, the concept of time is the focus of Oslo Pilot, a two-year research project (2015-2016), investigating art in public space and in the public realm with a particular focus on durational work, performance, and video art.

Led by curators Eva González-Sancho and Per Gunnar Eeg-Tverbakk, and funded by the City of Oslo, the Agency for Cultural Affairs, Norsk kulturråd and KORO, Oslo Pilot has introduced public art commissions, research programs, talks, events, and a series of publications with the goal of establishing foundations for a potential biennial in the city. The most recent symposium, “The Giver, The Guest & The Ghost: The Presence of Art in Public Realms,” featured four case studies of artworks by Thomas Hirschhorn (Gramsci Monument, 2013), Dora Garcia (Second Time Around, *forthcoming), Mette Edvardsen (Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine, 2010–ongoing), and Rahraw Omarzad (Every Tiger needs a horse, 2016). Respectively, concepts of social engagement and activism, authorship and repetition, historicity and exchange, and local vs. global politics were built into broader, cross-platform discussions about the responsibility of the artist or artwork as a visiting guest, roles performed by the artist and audience as giver and receiver, and the impressions or spectres left behind by a work or the experience of it.

Foto: Ane Mari Aakernes. Symposium The Giver, the Guest and the Ghost: The Presence of Art in Public Realms. General views, OSLO PILOT, 2016, Oslo

Over the course of three days, each artwork was presented in three formats: as keynote presentations by the artist, panel discussions with associated curators, theorists, or past participants, and in one-on-one sessions with related experts. The repetitive configuration was overkill at times, but then again, repetition was a theme of discussion. In practice, the configuration provided platforms for analyzing each work from multiple perspectives through video screenings, readings of research papers, live performances, and anecdotal stories from personal experiences or panelist presentations of their own creative work as tangential offshoots from the artist’s work being discussed.

Curator González-Sancho mentioned in conversation with me her interest in ‘90s video art as a guiding influence. However, from a broader perspective on ‘90s theoretical frameworks, many panelists revisited the continued legacy of post-structuralist philosophers such as Jacques Derrida and Gilles Deleuze, the politics of mediated experiences, rise of Relational Aesthetics, and decentralized engagement between the artist and spectator. The reasoning for reviving the ‘90s wasn’t clearly articulated. Perhaps it’s related to generational interests, or maybe a product of a relatively conservative environment accustomed to thinking of public art as static objects. Either way, the convening of academics, artists, and creative practitioners all pouring over theories about art effecting changes in the human psyche from before the era of social media and networks was refreshing: a time when mediated experiences were critically analyzed, and not the normalized baseline.

During a panel on Hirschhorn’s Gramsci Monument, a temporary community space built at the Forrest Houses public housing complex in the Bronx, NY, American artist and artwork participant Lex Brown offered a tender speech about understanding roles of privilege, and the affects of othering and exchange across racial, economic, and cultural divides. As a quieter counterpoint to an intensive group experience, Mette Edvardsen presented her living library performance in which select individuals become a ‘book’, each memorizing an entire book to recite to another person in an intimate, one-on-one experience. In her presentation, Edvardsen, who has a background in dance, discussed “liberating the text from the author” as the experience of the body becomes invisible in the process of ‘becoming’ and ‘reading’ a book. Garcia on the other hand, was stuck trying to explain an artwork that doesn’t exist yet with a series of non sequitur keywords like ‘protocol’ and ‘repetition’, but made up for the lack of content by cleverly inviting artist Michelangelo Miccolis to enact her performance The Artist Without Works (a guided tour around nothing), 2008, about the inherent radicalism in a refusal of the artist to deliver content, or even make sense. Rounding out the symposium, Rahraw Omarzad offered an earnest and sentimental story about his experience trying to create a peaceful bronze horse sculpture to complement the aggressive bronze tiger (in accordance with the fabled Norwegian poem Sidste Sang (the Last Song), 1870) that already stands in front of the central train station. Omarzad aims to install sister copies of his horse in Oslo and in his hometown, Kabul, Afghanistan, as a message of peace, honouring democracy and hospitality. Afterwards, immigrants from conflict zones in Afghanistan, Iranian Kurdistan, Palestine and Syria were invited to tell their stories of finding safe haven in Norway, as the city is currently experiencing an influx of refugees. Bringing in issues of global conflict launched discussions from micro to macro contexts, proving that recourses of symbolic gestures in public art still bear meaningful weight beyond local manifestations.

Foto: Espen Wallin. Symposium The Giver, the Guest and the Ghost: The Presence of Art in Public Realms. Rahraw Omarzad’s Workshop, OSLO PILOT, 2016, Oslo

While wandering across the city center, crisp Nordic light gleamed between the rippling waters of the bay and the new steel and glass Barcode Project—a hotly contested luxury high-rise development on the edge of the city center, where construction cranes practically outnumber road signs. Importantly, for every new government building erected, 0.5–1.5 percent of the budget is automatically earmarked for art, thanks to regulations set in place by City of Oslo, Agency for Cultural Affairs, in 2013, and a portion goes directly to Oslo Pilot. Although numerous public art projects regularly materialize, Oslo Pilot is funnelling attention and funding to lesser-supported, time-based, and ephemeral artworks in an attempt to activate the city’s incredibly rich scene. As the city itself grows and accelerates, long-standing support for the arts is trying to keep up. Established grants issued by the government for working artists have been shrinking in number, and lagging behind the inflation of average incomes, and the future of such programs feels uncertain to many involved. Do we need more biennials, or even more art? Art doesn’t exist in isolation. It takes makers, thinkers, and audiences to activate and re-activate its relevance over time. In the best-case scenario, realizing projects like Oslo Pilot, and the potential biennial in the works, spotlights the continued significance of supporting arts across the city, securing it’s future.

*Dora Garcia’s Second Time Around (Segunda Vez) will be included in a larger exhibition about her work at the Trondheim Kunstmuseum in 2018, curated by director Johan Börjesson.