The November–December 2016 issue of New Left Review features a fascinating piece by Antonio Gramsci Jr., the grandson of the Italian communist organic intellectual. On a visit to Russia in 1923, Gramsci Sr. met Giulia Schucht, who he would marry and have two kids with—Giuliano and Delio. In the piece, Antonio Jr., who is the son of Giuliano, talks about the political awakening he experienced through an extended visit to Italy and his effort to uncover traces of his grandfather in Russian archives. Here’s an excerpt:

Twenty years ago the Soviet Union collapsed—a society that, with all its defects, had represented the bastion of actually existing socialism and—paradoxically—helped ease the contradictions of western capitalism. It was around that time that I began to be interested in my grandfather. The Italian Communist party and the Fondazione Istituto Gramsci arranged a trip to Italy for me and my father to celebrate the centenary of his birth. We stayed in Italy around six months, in that time visiting all the places that had strong connections with the life of Antonio Gramsci, from Sardinia to Turi. (One of the most moving highlights of our pilgrimage was the concert I gave for the inmates in the prison in Turi, together with Francesca Vacca.) During those months, full of so many other fascinating events, I steeped myself in Italian culture and realized how important my grandfather is to it. Back in Russia, full of enthusiasm, I started to study Italian systematically and also read what little there was of his writing in Russian translation. My interest in Gramsci’s thought grew more and more strongly as I tried to understand what had happened in my country through the lens of his work. It was thanks to him that I now grasped the destructive role played by our intellectuals, who were responsible for the molecular shift in public opinion in favour of the new regime, which had led to the plunder of Russia, a process already begun during the years of perestroika. I didn’t become a Gramsci scholar—I’m a biologist and a musician—but my mental bearings had radically altered. Speaking of our own time, I can say that it is precisely at this turbulent historic moment that I sense the real need for the rise of an intellectual voice of Antonio Gramsci’s calibre to unite various factions that are divided and ideologically uncreative. These various factions can hardly be called an opposition, fused in the ‘historic bloc’ that alone would be capable of developing a correct strategic line in the struggle against the oppressive forces of the new regime, corrupt and cynical, that has ruled Russia for two decades now.

The decisive step towards my embrace of Gramsci occurred in the 2000s, when, as part of my collaboration with the Fondazione Istituto Gramsci, I began to look into the history of his Russian family, not knowing back then that those modest and disconnected attempts at reconstructing Gramsci’s history would turn into a proper research project. With it, I hope to have made my small contribution to the reconstruction of both the history of my country and the life of my grandfather. Giulia Schucht’s family was deeply involved with both. On the one hand there was the very interesting historical precedent of a part of the Russian intelligentsia, noble in background, betraying its class in the name of Revolution, distancing itself from its social ‘preconceptions’ and attempting to embrace the country’s new value system. On the other hand the Schucht family left a strong mark on my grandfather’s life, both personally and politically. This unusual family became the essential link in the extremely tight bond between Gramsci and revolutionary Russia. And Russia, I argue, is sometimes the key to explaining some of the most important and yet most puzzling episodes in Gramsci’s life. Let me talk about some of these.

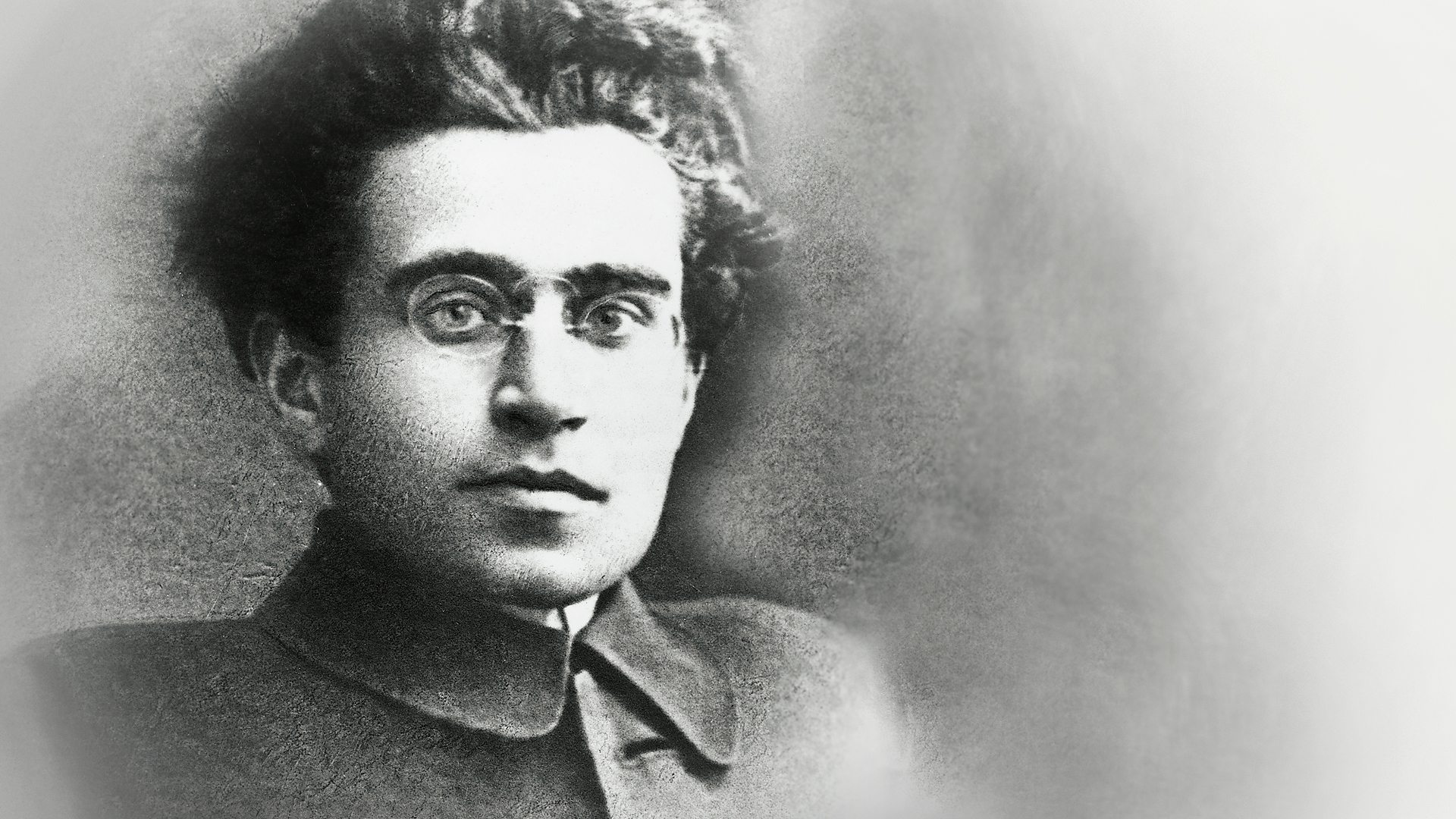

Image of Antonio Gramsci via BBC.