The excellent radical web magazine Viewpoint recently unveiled its latest issue, entitled “A ‘Struggle Without End’: Althusser’s Interventions.” In the introduction to the issue, Patrick King, an editor of the magazine and a doctoral student at UC Santa Cruz, examines how Althusser conceived the relationship between radical philosophy and radical political practice. Read an except of the introduction below, and check out the entire issue for vital essays on the enduring importance of Althusser to political struggle today.

The aim of this dossier is to extend this reading of Althusser: to view him not as an “Althusserian” or “structural Marxist” – a purveyor of a certain reading of Marx alongside a dogmatic importation of Spinoza – but as a Marxist who understood that theoretical work is a “struggle without end.” The existence of revisions and reorientations throughout his career should not be an offense or mark of an underlying incoherence; the situated, often reflexive character of Althusser’s thought serves to demonstrate that there is never a clean fit between theoretical practice and the actual balance of class forces – the conditions of possibility for thought. He no doubt would agree: is not the practice of symptomatic reading premised on the generative character of lacunae in written texts, and an understanding that no theory is ever “complete, without gaps or contradictions,” and thus never determined by a constitutive outside? And following Warren Montag’s recent account, even the dreaded invocations of “structural causality” and the “structured whole” of the capitalist social formation in Reading Capital were not made for want of ordering history and the struggles traversing any social formation; rather, these concepts were attempts to grasp the “determinate disorder of history,” as the knowable but irreducibly active relations between contradictory forces.

If anything, this emphasis on the contingent and provisional character of relations of force drove Althusser to elaborates a different mode of philosophical practice, as intervention. Like Spinoza and Marx before him, for Althusser the ultimate question confronting intellectuals and theorists is the following: what material effects have your works produced? We can add: how have they become “historically active,” or from a more partisan perspective, how have they been adopted and taken up in the organizational forms of class struggle? How have they “made things move,” faire bouger? The “Gramscian” inflection that Althusser’s works of the mid-70s indicate this desire to grasp the terrain of theory as one of contestation and struggle: “what occurs within philosophy maintains an intimate relation with what occurs in ideologies,: and “what occurs within ideologies maintains a close relation with the class struggle.”8 This refractory relationship means that the concepts we produce, the categories we focus on, the texts we publish, have determinate effects, and are a specific modality of practice.

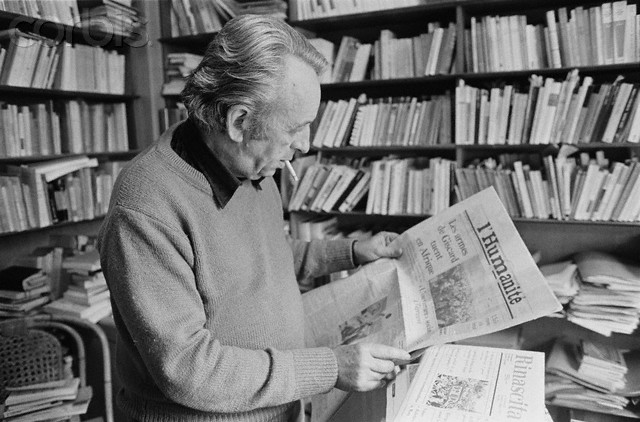

Image of Althusser via Viewpoint.