In Viewpoint magazine, Alberto Toscano examines Antonio Gramsci’s writings on folklore to help understand the present-day political gains of “late fascism,” as Toscano terms it. Gramsci, referring to the Italian proletariat of his own day, understood folklore as embodying a heterogeneous and disjointed worldview. It was the task of a revolutionary party, suggested Gramsci, to replace this with a more coherent and unified worldview, one that placed the proletariat in its historical role as the agent of the overcoming of capitalism. Today, writes Toscano, folklore has witnessed a resurgence on the political right, and its very incoherence is integral to the right’s success in present political conditions. Here’s an excerpt:

This question remains foremost on the agenda of any anti-systemic reflection in the present, especially as we witness not the farewell to class discourse announced or anticipated in the wake of the neoliberal ascendancy, but its toxic and distorted reflux – in that spectre of the industrial working class which has come to inhabit phenomena of reaction across the Euro-Atlantic region (Trump, Le Pen, Brexit…). The incoherence, heterogeneity, non-contemporaneity, contradictoriness and “bizarre” historical sedimentation that Gramsci once discerned in the phenomena of subaltern folklore is now spread across the social field, and pathological disorganization and disorientation is by no means the sad monopoly of the dominated. Perversely, among the “stratified deposits” that go on to make up contemporary (pre- or para-) political consciousness are distorted fragments of the productive modernity desired, for an emancipated proletariat and its allies, by Gramsci himself. Fordism haunts societies decomposed by the ravages of “regressive modernization” and primed once again for “authoritarian populism” (to employ two of the Gramscian constructs forged by Stuart Hall in the 1980s, in what has been recently judged “the most clairvoyant single example of a Gramscian diagnostic of a given society on record).” It is not simply that a progressive image of industrial modernity is past, but that it inhabits our political imaginary, as a reactive desire for a lost synchronicity and momentum – in what I have elsewhere tried provisionally to anatomize as an emergent “late fascism.” And in this late fascism, folklore is “official,” the incoherence at the “top” repeating and intensifying the confusion at the “bottom.” And the greatest challenge to those who remain oriented towards an egalitarian horizon – and “the long, dangerous, historical process of reconstructing society according to a different model” – is that fascistic, authoritarian and right populist solutions do not require a unified conception of the world and of life; or rather that, in Fredric Jameson’s terms, they can operate with the most degraded varieties of “cognitive mapping,” with the image of “totality as conspiracy.” If the illusion of the (Left) intellectual is that “ideology must be coherent, every bit of it fitting together, like a philosophical investigation,” this is an illusion that the right (especially once it leaves behind the rigor and asceticism of high bourgeois culture) need not entertain, happily flaunting its programmatic incoherence and rejection of the rationalist demand that politics have a logic, crafting its discourse to appeal in incommensurate ways to contradictory audiences. As even the commanding heights come to be inhabited by folklore, in its most derogatory acceptations, the challenges for a politics of solidarity and emancipation “riveted to difference” are formidable – whether they require, as Gramsci firmly believed, the unity of a conception of the world and of life, a hegemonic “philosophy,” remains an unsettled question. Gramscian diagnoses may not be followed by Gramscian prescriptions.

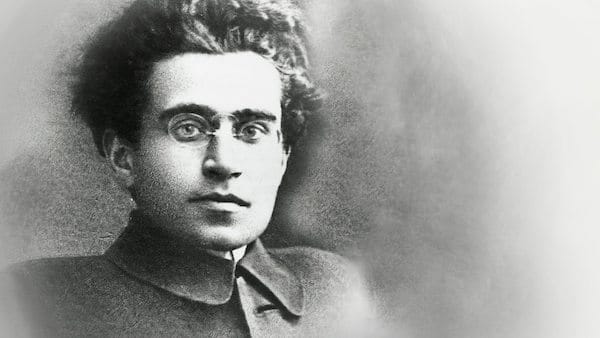

Image of Antonio Gramsci via MR Online.