The Verso website has an excerpt from The Age of Poets by Alain Badiou, a book in which the French philosopher argues for “an essential link” between

the twentieth century’s great poets and its liberatory communist movements. This link, writes Badiou, is founded in language, the primary material of poets and humanity’s most widely shared “commons.” Read a snippet of the excerpt below, or the whole thing here.

Can we understand this link between poetic commitment and communist commitment as a simple illusion? An error, or an errancy? An ignorance of the ferocity of states ruled by communist parties? I do not believe so. I wish to argue, on the contrary, that there exists an essential link between poetry and communism, if we understand ‘communism’ closely in its primary sense: the concern for what is common to all. A tense, paradoxical, violent love of life in common; the desire that what ought to be common and accessible to all should not be appropriated by the servants of Capital. The poetic desire that the things of life would be like the sky and the earth, like the water of the oceans and the brush res on a summer night – that is to say, would belong by right to the whole world.

Poets are communist for a primary reason, which is absolutely essential: their domain is language, most often their native tongue. Now, language is what is given to all from birth as an absolutely common good. Poets are those who try to make a language say what it seems incapable of saying. Poets are those who seek to create in language new names to name that which, before the poem, has no name. And it is essential for poetry that these inventions, these creations, which are internal to language, have the same destiny as the mother tongue itself: for them to be given to all without exception. The poem is a gift of the poet to language. But this gift, like language itself, is destined to the common – that is, to this anonymous point where what matters is not one person in particular but all, in the singular.

Thus, the great poets of the twentieth century recognized in the grandiose revolutionary project of communism something that was familiar to them – namely that, as the poem gives its inventions to language and as language is given to all, the material world and the world of thought must be given integrally to all, becoming no longer the property of a few but the common good of humanity as a whole.

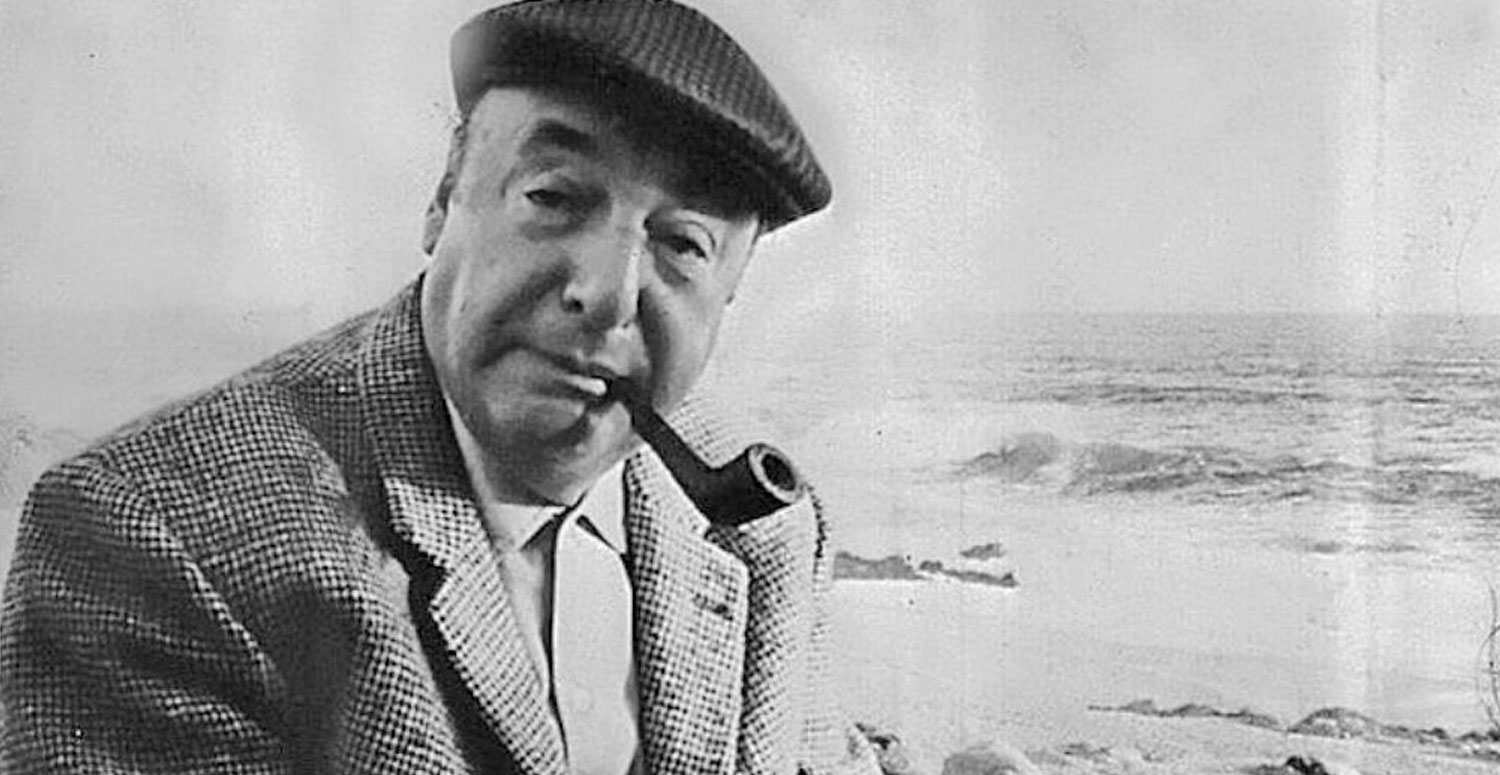

Image: Pablo Neruda.