Good news from Beijing: Ai Wei Wei has regained his passport after it was detained by the Chinese government for four years. The artist has been unable to travel install international exhibitions during this period, and was detained for 81 days with no charges in 2011. This hopefully marks a détente between Ai and Chinese officials. Read an excerpt of the report from Jonathan Kaiman and Julie Makinen for the Los Angeles Times below.

Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei regained his passport on Wednesday afternoon, more than four years after it was seized by authorities apparently in retaliation for his social and political activism.

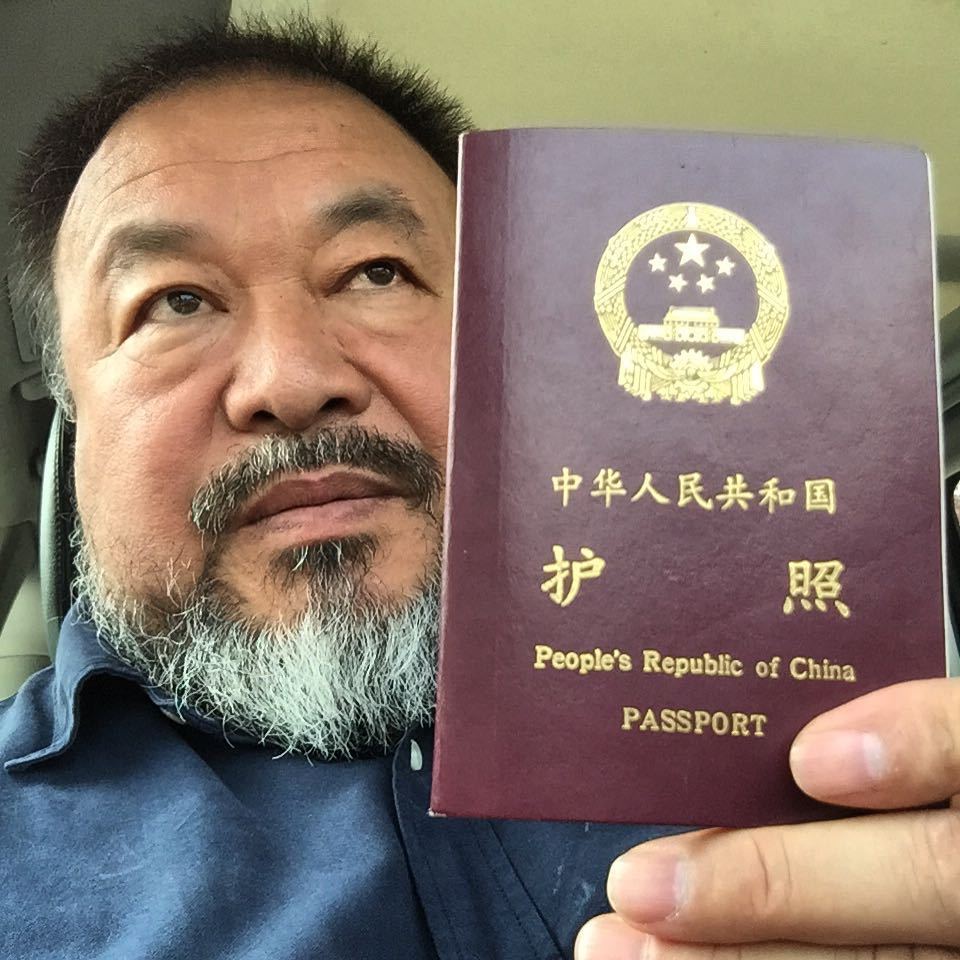

Ai posted a selfie to Instagram at about 3 p.m., holding his red People’s Republic of China passport up to the camera. “Today, I picked up my passport,” he wrote in a caption. The post has received more than 1,200 “likes” and nearly 200 comments, most of them supportive, as of press time.

Andreas Johnsen, director of the 2013 documentary “Ai Weiwei: The Fake Case,” said the news was a shock – but a pleasant one. “It’s extremely great, but it’s just sad it took so long,” he said.

Ai is best known for his postmodern, larger-than-life art installations, including ones that featured bronze zodiac animal heads, bicycle frames fused together and millions of hand-crafted porcelain sunflower seeds spread out on a gallery floor.

He has also established a reputation as a fierce government critic with a significant social media following. He led a campaign to investigate government corruption in wake of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, when shoddy school construction led to more than 5,000 student deaths.

In March, 2011, authorities detained him for 81 days under suspicion of subverting state power. After his release, police installed security cameras outside of his Beijing courtyard home, hit him with a $2.5-million fine for “economic crimes,” and confiscated his passport while he fought the case.

Recently, prominent galleries and museums in Germany, Britain and the U.S. have honored his work in major, one-man shows, yet Ai has been unable to leave the country to plan the shows or attend them once they are open.

“The authorities always promise me I will get my passport, but there is no clear indication when or at least nothing I can really rely on,” he told the Los Angeles Times in June 2014. "In the past 3 years I’ve asked maybe twice… there are so many engagements that [people] ask me to, they invite me, so I have to ask [authorities about my passport], otherwise I cannot just tell them I cannot go. I have to ask so I can tell them [no].”

"Another time I tried to have a medical check. I had brain surgery in Germany, in Munich, [in 2009 following a beating by Chinese police]. "I haven’t had a routine check up for a long time, which is not so good, so I asked. Last time I asked was about three months ago. They said they received my requirement but they don’t give to me. …”

Recently, authorities have shown signs of easing toward Ai. He has been able to travel within China, and in June, he opened his first solo show in the country in years at Beijing’s 798 Arts District.

The show is not overtly political; it consists of a 400-year-old Ming dynasty-era ancestral hall that Ai and his assistants disassembled and reconstructed in two exhibition spaces, dividing the wooden structure between two different art galleries.

Ai’s @Large show on Alcatraz, which closed in April, attracted more than 896,000 visitors. Ai was unable to travel to California to supervise installation of the show, forcing exhibit organizers to make multiple trips with Beijing to confer with him on the project.

The Alcatraz show dealt with themes of incarceration and freedom. “As an artist, I live in a society where freedom is incredibly precious. We strive for it daily and put forth a great amount of effort, sometimes sacrificing everything to protect this value, to insist on freedom,” Ai said in materials prepared for the exhibition.

Since his release from 81 days of detention in 2011, Ai said he had been held in “what some would call a ‘soft’ detention.”

“The government has never formally charged me, but in China my name has been censored on the Internet, in the media, and even in exhibitions featuring my own work. Even after sixty-five years of rule, the government has never recognized the rights of the people,” he added. “We cannot vote, and we have no independent judicial system or independent media apart from state control. Freedom, indeed, is a word that carries a great deal of weight for the Chinese people.”