In Salvage journal, Richard Seymour has a fascinating, masterful essay that challenges the conventional wisdom, propounded most famously by George Orwell, that good writing must be “clear” writing. Seymour demonstrates that all writing, not matter how ostensibly “direct” or “unadorned,” is artifice through and through. To deny this is to deny not only the materiality of writing, but also its playful, fantastical dimension. Here’s an excerpt:

There is, beyond this, a more troubling philistinism of the Left. This often takes the form of pseudo-naturalism: naturalism that doesn’t even know it’s a literary form. It treats language as a vehicle, a politically neutral instrument through which to convey information and exhortation, and style as superfluous to political meaning.

There is no Philistine Manifesto outlining this very British school of thought, because it is so pervasive, so commonsensical, that no one bothers to try to defend it. In part, it derives from the habitus of some professional writers, journalists, who are trained to report by learning what the composition scholar Nancy Welch called the ‘real-tight structure’. This allows one to write up a motorway pile-up, or gruesome multiple murder, as if it made sense. Suppressing dissonance and disturbance in the text is part of the way it achieves authority, conveying the impression of objectivity. Likewise, many students who are trained to write academic essays are encouraged to expunge themselves from their writing – excepting cursory gestures to ‘reflexivity’ – and are rebuked if they don’t. The resulting ‘unaffected’, ‘clinical’ style establishes authority. It is a rhetorical technique, a means of persuasion. This, of course, teaches people a certain discipline, but it also teaches them to hate writing. It makes it dull and uninteresting, and turns writing into a guilt function: as something you have to do but can never quite bring yourself to do. By making people into bad writers, it makes them believe they can’t write.

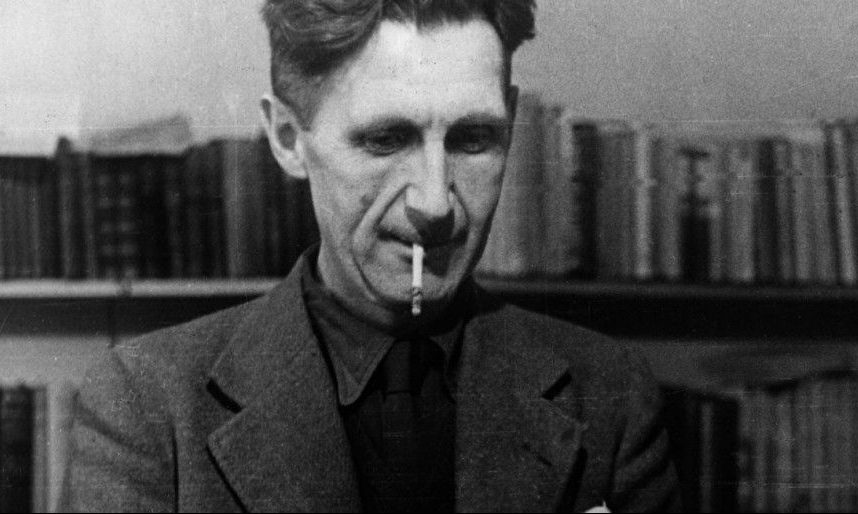

Image of George Orwell via Jacobin.