On the emancipatory possibility of decentered exhibitions

We the undersigned artists, writers, musicians, and researchers who participated in various chapters of the current documenta 14—Exhibition, Parliament of Bodies, South as a State of Mind, Listening Space, Keimena, Studio 14, An Education, EMST collection, and Every Time A Ear di Soun—wish to share some thoughts about the possibilities and potential of documenta. Firstly, we acknowledge those participants in documenta 14 whom we have not been able to reach at the time of writing, those with whom we could not get to consensus, those participants no longer living, and especially those who passed away while participating in documenta 14. We write this in the context of the invitation of “Learning from Athens,” and the idea of first unlearning the familiar. We also take note of documenta’s specific history as a response to the evil of the Second World War and the Holocaust. We see that initial, painful legacy evolving toward an imaginative and discursive space that can contribute toward challenging war capitalism, unjust borders, and ecological suicide.

The initial iterations of documenta rose in the shadow of rebuilding, after a World War that caused Adorno to disavow a future for poetry. From the 1990s, the exhibition joined a global turn toward decentering the Western art-historical canon, by beginning to emancipate institutions, venues, and universities. There was a welcome, and overdue, acceleration of the presence of artists, theorists, and thinkers from the Global South, starting from documenta 10 (Catherine David), continuing through documenta 11 (Okwui Enwezor), documenta 12 (Roger Buergel / Ruth Noack), and documenta 13 (Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev). documenta also began a spatial decentering, initiated by documenta 11 with platforms in Berlin, Vienna, New Delhi, St. Lucia, and Lagos. This was followed by documenta 12 magazine, a network of 100 magazines world-wide, and documenta 13, with satellite projects in Kabul, Alexandria, and Banff. It is in line with documenta’s long heritage of decentering, and decolonizing, that we welcomed the decision to launch documenta 14 as a dialogue between Athens and Kassel.

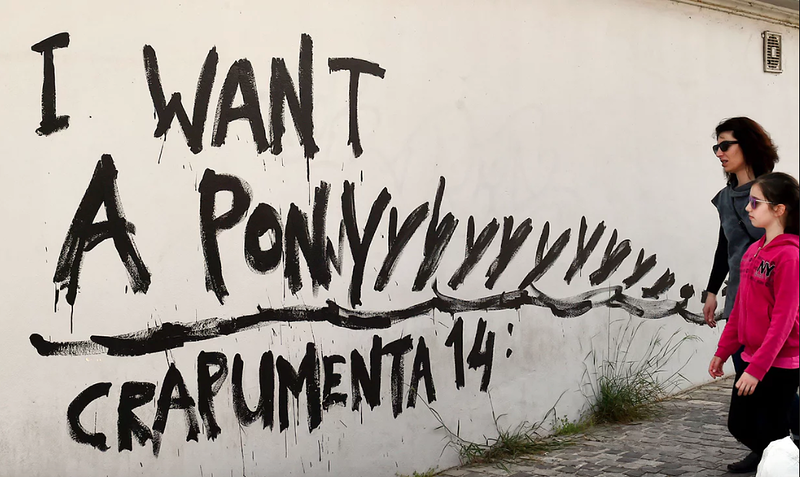

documenta 14’s Athens chapter began a full two years before the official opening, with the launch of the South as a State of Mind journal in 2015, the weekly public program Parliament of Bodies in 2016, and finally, the opening of documenta 14 | Athens in April 2017, two months before Kassel. documenta 14’s curatorial team worked to encourage autonomous spaces, free of authoritative statements or frameworks. However, criticism appeared immediately, focusing on budget and infrastructure, with far less attention paid to the artworks, journal, radio, public TV, live music, education, and public programs. A few critics did raise some points that were also being debated among the artists and curators. One of those centered on the challenges of working with local communities in an environment of equality and partnership, while working within large exhibition infrastructures. Another question was whether large exhibitions are the best venue for breaking down discursive hegemonies. documenta 14 had a shared commitment to preserving the autonomy of local spaces and communities, and conducting conversations around culture within a dynamic of mutual exchange, respect, and curiosity.

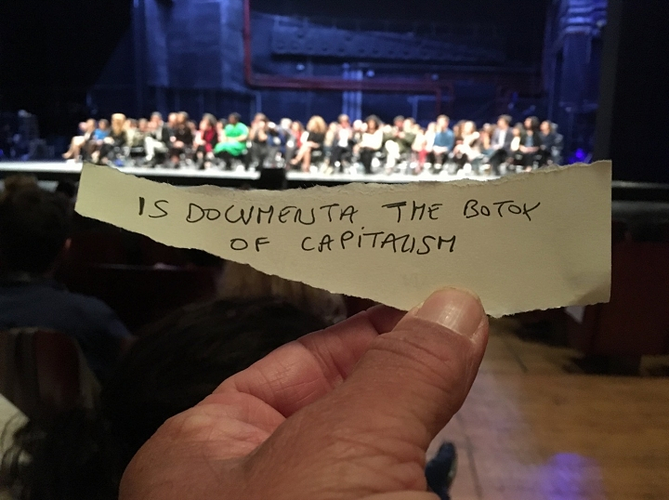

Recently, criticisms of documenta 14 have been expanded to suggest that a deficit in the operating budget is primarily due to the Athenian chapter of documenta. We are concerned about this urge to put ticket sales above art, and we believe that Arnold Bode would have rejected this as distorting the purpose for which he gifted documenta to Kassel. We applaud the decision by documenta 14 to not charge ticket prices in Athens. We should also consider the responsibility to address the economic war fought by European institutions against the Greek population, during the recent debt crisis. We feel that casting a false shadow of criticism and scandal over documenta 14 does a disservice to the work that the artistic director and his team have put into this exhibition. Shaming through debt is an ancient financial warfare technique; these terms of assessment have nothing to do with what the curators have made possible, and what the artists have actually done within this exhibition.

What should be highlighted are the positive impacts of exchanges within documenta, including the decentering that occurred through the exhibition. This has caused a creative friction that is an active dialogue between citizens, communities, and institutions of Athens, Kassel, and the rest of the world. This is only a first step, and conversation must continue in coming years. In fact, more such moves of dislocation from comfort zones, and inclusion of multiplicity of voices, many standing outside of western hegemony, should be the future. What we do not need is a neoliberal logic, as well as its institutional critique, that does not allow the possibility of alternative methods, stories, and experiences.

One aspect that makes documenta remarkable is its support of large numbers of artists who are not represented by commercial galleries, and in fact work in non-material, ephemeral, and social practices. Many come from regions and countries still underrepresented in major art events. Naturally, many of the works produced here very consciously suggested proposals for equality and solidarity. We understood this exhibition to be a listening documenta. The curatorial team took care to listen closely and carefully to artists, rather than imposing a top-down curatorial will. The exhibition tried to be inclusive, as well as specific, emphasizing people and stories from the so-called periphery, and voices belonging to those who have faced, and overcome, hardship. Whether in crisis or inflection point, enquiry was encouraged, challenging the more frequent move of wanting to own other peoples’ understanding. The curatorial innovation was to create the space for such an encounter, in Athens and Kassel.

There are many interventions, by the artistic director and curatorial team, which brought together new configurations and dialogue between generations of artists, much of which is invisible to the critics. Also crucial has been the displaying of rare historic material, some of it centuries old and from all parts of the world, some of which has never been displayed in a museum. By commissioning new work in dialogue with centuries-old heritage, new alliances were created across territories and times. The juxtaposition of stories from all over the globe can be disorienting, but that is precisely the point of the structure of this exhibition. Large gestures have to be measured alongside hundreds of small ones to make a complex whole, all going towards globalizing the art historical canon. The challenge for all of us—artists, critics, and audiences—has been to experience that complexity, while subjected to practical economic constraints. We need to think of more economically egalitarian ways of viewing a large exhibition, while resisting the dominant narrative that is singularity (“the Athens model”) over complexity (what actually happened in Athens and Kassel).

documenta was founded as a brave response to a dark history. The 1933 Nazi regime received support from Nuremberg and Kassel, because of the presence of the arms industries. On February 11, 1933, eleven days after taking power, Hitler spoke at the Friedrichsplatz in Kassel. On November 7, 1938, two days before Kristallnacht in other German cities began, Kassel and surrounding villages saw anti-Jewish pogroms. In archival footage of trains carrying people to concentration camps, the insignia “Deutsche Reichsbahn Kassel” is visible on some carriages. After 1945, in order to erase this Nazi legacy, Nuremberg hosted war crimes trials, and, ten years later, Kassel hosted the first documenta. Kassel’s central Friedrichsplatz was bifurcated, so that no spatial trace of the 1933 rally remains. In light of this unique founding history, documenta’s unique mission has always been, and must continue to be, encouraging conversations in the contemporary arts that can oppose the spectres of nationalism, neo-nazism, and fascism that are still haunting the planet.

The world has transformed many times over since 1955. Western Europe is no longer the center of contemporary exhibition making. It is being challenged to take its place as one among equals, as Asia, Latin America, Africa, Middle East, Southern and Eastern Europe come forward to claim their presence. The current documenta continues the arc of the previous four documentas, by highlighting the edges of Europe, the voices of Global South realities, and the presences that press against heteronormativity. Receiving the world, as equals, contrary to anxieties, also contributes to radiance. The contemporary arts no longer looks toward a European exhibition to lead the way in ideas about what art can do, and what it should do. However, Kassel does exercise influence in contemporary art discussions that are emerging from many locations (Bamako, Beirut, Bucharest, Cairo, Dakar, Gwangju, Havana, Istanbul, Jakarta, Johannesburg, Kochi, Ljubljana, Mexico City, Moscow, New Orleans, Sao Paulo, Shanghai, Sharjah, Warsaw, Zagreb, and numerous others). We ask the documenta supervisory board to vigorously defend the curatorial team’s vision of documenta 14, and future curatorial teams to continue to make exhibitions that are accessible to all, and that decenter art history, challenge war and nationalism, and fight against the poisoning of the planet.

Contact: documenta14.artists@gmail.com

Signed,

- Aboubakar Fofana

- Achim Lengerer

- Agnes Denes

- Ahlam Shibli

- Aki Onda

- Akio Suzuki

- Akinbode Akinbiyi

- Alessandra Pomarico

- Alexandra Bachzetsis

- Alvin Lucier

- Amar Kanwar

- Amelia Jones

- Anca Daučíková

- Andreas Angelidakis

- Andreas Kasapis

- Andrew Feinstein

- Andrius Arutiunian

- Angela Dimitrakaki

- Angela Melitopoulos

- Angelo Plessas

- Angela Ricci Lucchi

- Anna Papaeti

- Anna Sorokovaya

- Annie Vigier

- Annie Sprinkle

- Anthony Burr

- Anton Lars

- Antonio Negri

- Antonio Vega Macotela

- Apostolos Georgiou

- Arin Rungjang

- Artur Zmijewski

- Ashley Hans Scheirl

- Athena Katsanevaki

- Banu Cennetoglu

- Ben Russell

- Beth Stephens

- Bonita Ely

- Boris Baltschun

- Boris Buden

- Bouchra Khalili

- Brett Neilson

- Cana Bilir-Meier

- Cecilia Vicuna

- Christina Kubisch

- Christos Chondropoulos

- Click Ngwere

- Colin Dayan

- Conrad Steinmann

- Constantinos Hadzinikolaou

- Dan Peterman

- Daniel Garcia Andújar

- Daniel Knorr

- David Harding

- David Lamelas

- David Schutter

- David Scott

- Debbie Valencia

- Denise Ferreira da Silva

- Dimitris Papanikolaou

- Dimitris Parsanoglou

- Dmitry Vilensky (Chto Delat)

- Edi Hila

- EJ McKeon

- Elisabeth Lebovici

- Elle Marja Eira

- Emanuele Braga

- Emeka Ogboh

- Emily Jacir

- Eric Alliez

- Eva Stefani

- Evelyn Wangui Gichuhi

- Feben Amara

- Franck Apertet

- Franco “Bifo” Berardi

- Ganesh Haloi

- Gauri Gill

- Geeta Kapur

- Gert Platner

- Geta Bratescu

- Gordon Hookey

- Guillermo Galindo

- Guillermo Gomez-Pena

- Hans D) Christ

- Hans Eijkelboom

- Hans Haacke

- Hiwa K

- Ibrahim Mahama

- Ibrahim Quraishi

- Irena Haiduk

- Iris Dressler

- Itziar González Virós

- Jack Halberstam

- Jan St) Werner

- Jakob Ullmann

- Jess Ballinger-Gómez

- Joana Hadjithomas

- Joar Nango

- Johan Grimonprez

- Jonas Broberg

- Jonas Mekas

- Josef Schreiner

- Joulia Strauss

- Katalin Ladik

- Kettly Noël

- Lala Meredith-Vula

- Lassana Igo Diarra

- Lenio Kaklea

- Lois Weinberger

- Lucien Castaing-Taylor

- Lukas Rickli (Kukuruz Quartet)

- Macarena Gomez-Barris

- Magali Arriola

- Manthia Diawara

- Maret Anne

- Maria Eichhorn

- Maria Hassabi

- Maria Iorio

- Marianna Maruyama

- Marie Cool and Fabio Balducci

- Marina Gioti

- Marta Minujin

- Mary Zygouri

- Mata Aho Collective

- Mattin

- Michel Auder

- Mike Crane

- Miriam Cahn

- Molly McDolan

- Mounira Al Solh

- Moyra Davey

- Naeem Mohaiemen

- Nairy Baghramian

- Narimane Mari

- Nathan Pohio

- Neil Leonard

- Nelli Kambouri

- Neni Panourgiá

- Nevin Aladag

- Niels Coppens

- Nikhil Chopra

- Niklas Goldbach

- Nikolay Oleynikov (Chto Delat)

- Nilima Sheikh

- Nomin bold

- Olaf Holzapfel

- Olga Tsaplya Egorova (Chto Delat)

- Otobong Nkanga

- Oxana Timofeeva (Chto Delat)

- Panos Alexiadis

- Peaches Nisker

- Piotr Uklanski

- Panos Charalambous

- Pavel Braila

- Pélagie Gbaguidi

- Peter Friedl

- Philip Bartels

- Philipp Gropper

- Prinz Gholam

- Prodromos Tsinikoris

- Ralf Homann

- Raphaël Cuomo

- Rasha Salti

- Rasheed Araeen

- Raven Chacon

- Rebecca Belmore

- Regina José Galindo

- R) H) Quaytman

- Rick Lowe

- Roee Rosen

- Roger Bernat

- Rosalind Nashashibi

- Ross Birrell

- Samia Zennadi

- Samnang Khvay

- Sanchayan Ghosh

- Sandro Mezzadra

- Sanja Ivekovic

- Sarah Washington

- Serdar Kazak

- Serge Baghdassarians

- Sergio Zevallos

- Shu Lea Cheang

- Simon(e) Jaikriuma Paetau

- Simone Keller

- Sokol Beqiri

- Stanley Whitney

- Stathis Gourgouris

- Stratos Bichakis

- Suely Rolnik

- Susan Hiller

- Synnøve Persen

- Taras Kovach

- Thais Guisasola

- Tracey Rose

- Theo Eshetu

- Ulrich Schneider

- Ulrich Wüst

- Valentin Roma

- Vasyl Cherepanyn

- Verena Paravel

- Vijay Prashad

- Virginie Despentes

- Vivian Suter

- Wang Bing

- What How and for Whom (WHW)

- William pope)l

- Yael Davids

- Yervant Gianikian

- Zafos Xagoraris

- Zoe Mavroudi

- Zonayed Saki

Image: documenta 14 artists preparing to perform Jani Christou’s “Epicycle” (1968) at opening of documenta 14 press conference in Athens, Megaron, 6 April, 2017. Image: Mathias Völzke.