In the Los Angeles Review of Books, literary scholar Gayle Rogers reviews Outsider Theory: Intellectual Histories of Unorthodox Ideas by Jonathan P. Eburne. “This book is a truly weird read,” writes Rogers, “and I mean that as a serious compliment.” He lauds Eburne’s book for its subtle and original methodology, and for showing that the intellectual “inside” can’t exist without the “outside,” and vice versa. Here’s an excerpt:

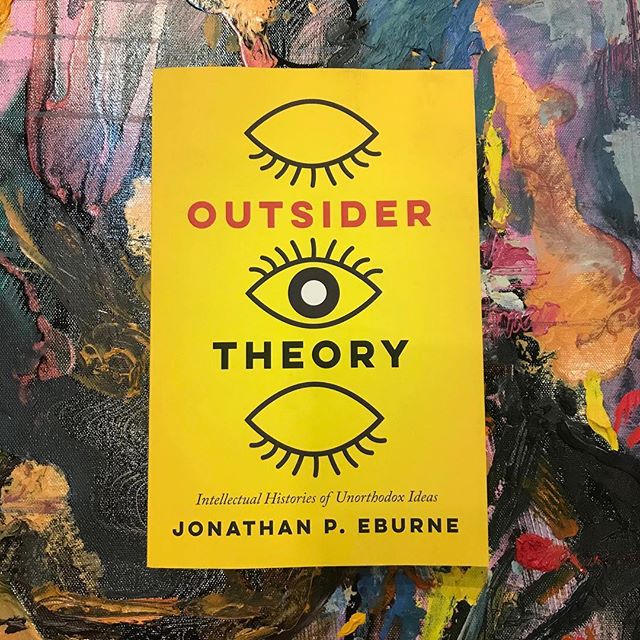

More pointedly, what happens if we follow the lead of Jonathan Eburne’s stimulating and highly original new book, Outsider Theory: Intellectual Histories of Unorthodox Ideas , and “adopt this art historical provocation [of art brut ] as a heuristic for the study of modern intellectual history”? In “taking up a detailed investigation of the ways in which marginal or otherwise underground, hermetic, or far-fetched ideas circulate,” Eburne answers this question by placing matters of epistemology front and center. The fundamental questions of outsidership, that is, are questions of how we know what we know; in this observation, Eburne’s capacious title and ambitious scope become a real provocation.

This book, therefore, is not a story of boundary-creation, or of the sanitization of outlandish ideas. It is an attempt to understand what the inside looks like from the outside and how texts move around various borders, especially when outsider cases become touchstones of widespread cultural debate, from academic journals to History Channel specials to Reddit threads. Outsider Theory thereby charts, in fine-grained detail and wide-ranging archival research, a course through the overlapping intellectual and reception histories of a dizzying array of texts, ideas, and movements. Like its relative, Kevin Young’s Bunk , Eburne’s book traverses high and low cultures, from the Gnostics to The Da Vinci Code , in considering works and figures who were forced outside (by racial difference, for example), and those who remain outside (by neglect, however banal), as kin. Their polythetic relations and “illegitimate knowledges” must be reconstructed, he argues. Unlike most scholars, Eburne is equally at home when making innovative arguments about the ontological implications of digitized Gnostic gospels and when arranging Marcus Garvey and the Marquis de Sade into argumentative juxtaposition.