Tehran Museum Vault Where Works by Modern Masters have been hidden for years. Photo via bloomberg.com

by Mohammad Salemy and Stefan Heidenreich

In October 2015, after the signing of an agreement between Hermann Parzinger, the president of the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, and Majid Mollanoroozi,the director of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMoCA), a select group of artworks from the museum’s collection were to be exhibited internationally for the first time in Berlin followed by an additional exhibition at Maxii Museum in Rome. The Berlin exhibition was supposed to include 60 paintings, amongst them works of artists like Rothko and Pollock. It was set to open on December 4, 2016. Full-scale preparations had been made, and even tickets were already on sale. However, after a series of protests and social media campaigns by Iranian artists and cultural activists, the show has been delayed and no new dates set for the opening. The official reason given by the Germans for the delay was the stepping down of the Iranian minister of culture Ali Jannati. However, little has been reported in the western art press about the real issues involved; nor have they addressed the protests by the Iranian art and culture community.

The controversy inside Iran regarding the exhibition revolves around the deal made between the Iranian and European museum officials. Those opposing the exhibition allege that the secret agreement has intentionally left the lending of artworks to Europe prone to lawsuits and property claims by the pre-revolution owners and buyers of the works. Recently, collectors from around the world have flocked to Tehran in order to visit the collection. It remains unclear if they were assessing the works and/or striking preemptive deals. The widespread rumors of shady dealings regarding the collection have prompted Farah Diba, the wife of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi and the main patron of TMOCA before the revolution, to deny the existence of such plans. In a well-publicized interview on November 25 with Kayhan-London, she denied having any plans to claim the artworks designated for exhibition in Europe.

The most outspoken character in the TMOCA affair has been Afshin Parvaresh, a journalist and cultural activist who resides in the US. His social media publicity about the issue has slowly gained momentum during the last 6 months and has helped turn the lending of TMOCA artworks and the fate of the larger collection into a crucial political issue inside Iran. Parvaresh, along with anonymous TMOCA staff, and several independent Tehran-based artists who wish to remain anonymous insist on the existence of secret deals to transfer artworks from TMOCA to western collectors. The opposition on the issue, which includes the Association of Iranian Painters (http://www.iranpainters.com/?m_id=793&id=397) as well as Lili Golestan the owner and operator of the Golestan Gallery (http://www.iranpainters.com/?m_id=793&id=461) all agree that general comments and secrecy surrounding the details of the proposed exhibitions in Europe are signs of bad deals made between the TMOCA management and the European museums. Parvaresh, however, goes as far as to claim that lawyers in Europe have already begun preparation to sue the TMOCA and the German museums and will try to return the works to original owners who will flip them for large sums of money to western collectors. Parvaresh suggests that it is very likely that those who made the original purchases for TMOCA in the 1970s, including the Royal Family itself, may have already made lucrative deals with corrupt TMOCA officials and collectors in the west, and perhaps this is why the agreements between European officials and their Iranian counterparts have been kept secret and never publicly released. Adding to the suspicions, on November 20th, the incoming Iranian Minister of Culture Reza Salehi announced that the lending of works to Europe has been halted.

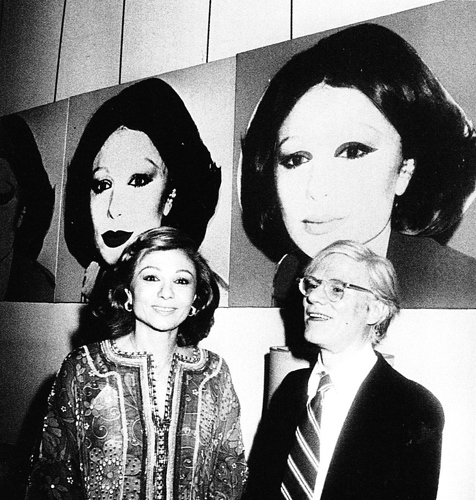

Farah Diba and Andy Warhol

BACKGROUND

Built by the architect Kamran Diba, the cousin of the Queen Farah Diba, opened in 1977. The Queen had also played an active role in assembling the museum’s immense collection. She was lucky because the 1970s was the right time for buying western modern art. The economic crisis had suppressed the prices, and for a comparatively small budget of 100 Million USD she was able to assemble one the richest collections of Western modernist art, which in addition to Pollock and de Kooning includes works by David Hockney, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenburg, Andy Warhol, Max Ernst and Francis Bacon. The collection also includes thirty works by Picasso. Less than two years after TMOCA’s opening, the Monarchy was overthrown by Islamic revolutionaries. The museum’s collection, along with whatever art was salvaged from the royal palaces, was brought together and kept in the TMOCA vaults where they have spent most of the last 40 years. As of now, the combined collection is regarded as one of the richest collections of not only Western, but also Iranian modern art, valued at a price of 3 to 5 Billion USD. In 2010, one single painting, Jackson Pollock’s Mural on Indian Red Ground was valued at 250 Million Dollars by the auction house Christie’s.

In the last forty years, only a small percentage of the artworks have ever been on display. Some which have erotic and/or sexual content, like Renoir’s Gabrielle https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gabrielle_with_Open_Blouse (1907), a painting of a woman with open blouse and naked breasts, have never been seen. Only on very rare occasions were single artworks allowed to be loaned abroad. Through a rare loan by TMOCA, a Max Ernst painting titled Histoire Naturelle (1925) was shown in Germany in 2012.

Distinguishing between public and private cultural initiatives carried out by the Iranian Royal family in the 1970s was blurry at best and the establishment of TMOCA was no exception. Even after its opening, the museum remains a semi-private enterprise of which Farah Diba was personally in charge with curators David Galloway and Donna Stein acting on her behalf. In addition, there are works in the TMOCA vaults which were originally purchased by the Queen for the Royal Collection. Officials now confirm earlier allegations by Parvaresh that it remains unclear who nominally owns many works at the museum since there are no detailed list of the paintings belonging to the collection. Parvaresh believes that the paperwork from the pre-revolution era has mysteriously gone missing from TMOCA archives since they initially began thinking about the museum’s privatization.

In fact, the recent controversy is not the first time Iran’s art community has protested the government plans for the future of TMOCA. Plans to privatize TMOCA date back to 2001, during the reign of the reformist president Khatami who faced fierce opposition by the Iranian art community. The protests included the well-publicized parliament sit-in of Mrs. Masoomeh Seyhoun, owner of the prestigious Seyhoun Gallery in Tehran, which helped to prevent TMOCA’s privatization. The plan was eventually shelved by the conservative Guardian Council but not rejected. With the return of the reformists to power in 2013, the management began proposing other schemes for the museum’s privatization and the eventual sales of some of its holdings. In April of 2016, a new attempt was made to designate the Rudaki Institute, a private foundation named after a Persian poet of the 9th century, as the caretaker of TMOCA. Roudaki is already in charge of two Iranian orchestras and several provincial museums. When the privatization plans were announced again in April 2016, the Tehran art crowd took to the streets and protested. Once more, the plans were shelved. Instead, the management began entertaining the idea of exhibiting parts of the collection in the West.

Does TMOCA hold all the property rights for the works in its collection? Can Farah Diba and others around the Royal Family who in the 1970s purchased works for the museum make property claims once these artworks are in international jurisdictions? In rare instances in the past, European state guarantees have been effective, but the relationship between the state and the investors has changed during recent years. Mutual trade agreements give private investors an increasingly strong hand over state legislation. Nobody knows what avenues lawyers might find in order to contest ministerial guarantees, favor private property claims, and block the return of the works to Iran.

The collection so far has survived, albeit in terrible conditions, thanks to the foreign and self-imposed isolation of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The end of sanctions and the atomic deal with the US means the opening of Iran. Economic relations are bound to return to the new normal. This is supposed to include the transformation of the regime into a “normal” states, with all the strings and requirements attached. Privatization of cultural assets is a mandatory part of this process. TMOCA’s management even thinks that profits from exhibiting the works in the West, including sales of some of the work, may pay for the restoration and storage of the collection as a whole.

Official proclamations, promises, and guarantees are met with mistrust, particularly in Tehran where it is feared that another part of the country’s cultural heritage, unlike Persian antiquities which also include Western cultural artifacts, is being transferred from one bunker, that just opened after 40 years, to the international art market and its private storage houses.