SUPERCONVERSATIONS DAY 81: SAM SAMIEE & MOHAMMAD SALEMY RESPOND TO HASSAN KHAN & NATASHA GINWALA, “SOAKING IN THE DAILY CURSES: A CONVERSATION”

#On (Corruption) X (Corruption) or the Non-place of Public Intellectuals in Bloody Dictatorships: A Conversation

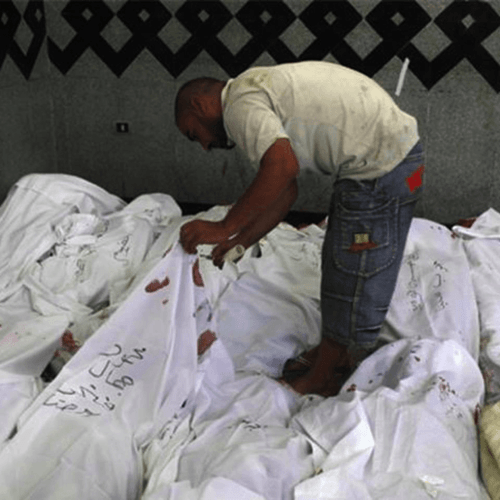

Clashes in Egypt result in the many deaths (reports “vary from 60 and 120”) of those that supported the ousted President Mohamed Morsi [Source: Aljazeera).

Sam: Let’s begin

Mohammad: Yes. I am here.

Mohammad: I think we should try to first talk about the premise of the conversation, the frame. What is the frame of this curator/artist conversation? Like any other text, the manuscript of this conversation has an invisible frame that holds it together. This text actually is not that all over the place. What do you think that frame is?

Sam: I can have some guesses! It is it an interview which looks at the certain aspects of Khan’s practice retrospectively and arrives at the issues with which he is dealing on a daily basis as the title suggests.

Mohammad: Yes, this is what I was going to say, the scope of this interview is limited to Khan’s existence as an artist, his interests and artistic intentionalities in the larger context of Egyptian history and culture as an Arab nation state. But even this context is claustrophobically limited to a short period of time. I mean, when we look at the calendar, I see the year 2015. A tumultuous gap of three years separates the material basis of the conversation - the historical and political realities of Egypt in Documenta (13) - from our now-moment, a gap in which Egypt went through a democratic presidential election, resulting in the formation of a government by the Muslim Brotherhood, one of the earliest Islamist organizations in the Middle East. Then the country experienced both a counterrevolution against the quickly establishing Brotherhood order and a bloody coup by the military which at the expense of several thousands of dead bodies and many more in prison, including the president elect, returned the country back where it was before the Arab Spring, if not even further back. There is so little of this context explicitly discussed in the interview even though one can smell it all over the place.

Sam: Interesting, I was going to say this gap may not have changed as far as the history of Egypt. In “corrupted intellectuals”, Khan discusses his attitude as an artist towards Egyptian intellectuals and their relationship to the state, but unfortunately he is silent about the relationship of Egyptian subjectivity to the Ottoman empire. With the rise and fall of the Muslim Brotherhood such relations are even more repressed. He gets very close to addressing this via his reflections on his daily observations at a local traditional coffeeshop, as the starting point for seeing the invisible historical flashbacks in these age old social practices.

The interview kept conjuring in my mind what I know of Asef Bayat’s ‘Revolution without Movement, Movement Without Revolution,’ i.e., the idea of non-revolutionary movements versus non-movement revolutions and how they can explain contemporary visible and invisible social and historical navigations, or the concern of the economy of signs in a text, or what is the signifying weight one wants to assign to a certain subject or concept in their text? If I am right, we are reading the self description of an art practice with a very defined context. What exactly is beyond the limited context that the practice is offering to the viewers, in this case of readers?

Mohammad: Ok, here l will return to the question of framing. I say this because as a curator, I have always been trying to exchange the place of the artist and the context opposite to this interview. For me the artist should never be the main meal and the context a side dish, but the other way around. For me, the artist is almost always an excuse for larger stuff. The way to locate an artist or an art practice is not by putting it in the centre but really by centering it. If all a work of art does is the production of subjectivity, why do we even need art since every human being, given the cheap possibilities of representational industry/economy is constantly producing creative subjectivities? For me what should be the centre of the discussion is the context. The context should come first and then the artist ought to be placed in this context. So I guess it is not that I am asking for the destruction of the frame but maybe a different kind of frame.

Sam: Or exposing the curator’s frame by the artist, maybe elaborating or expanding the frame, its constitutions and its elements? To me, as the one who is usually introduced to the public as an artist it is not very different. It took me a very long time to realize the problem with the context of my work was its lack (the Iranian art scene, or generally the Iranian high culture) and that was the beginning of the painstaking task of rewinding and opening and reexamining what has made the context I have been situated in by myself.

Mohammad: Don’t get me wrong. I don’t blame Khan for this. This is the logic of the contemporary art world and Khan, even though he is presented as the centre of this particular conversation he is really only a player in a much larger networked system, one whose logic lacks a proper understanding of how art relates to its historical, social and political contexts. But let’s also not forget how by playing along these logic, artists, especially the ones from the periphery, get rewarded for their complicity with important exhibitions, awards, editorial texts, etc. So there is an exchange that is going on right in midst of the exchange between the curator and the artist. However we know in this relationship curators are often more powerful, even when they are not directly in an exchange with the artist, a curator with less art capital is actually is working with a well-known artist - the important curators are watching and taking notes.

Sam: Maybe it is not blaming Khan, but those that I have admired, even when I have been unaware of the reasons why. I am referring to those artists that are generous towards the audience in regards to understanding the context of their works. basically what I am trying to say is, regardless of the quality of the actual art, some artists perform this contextualization better than others. Being open about the context of one’s work is not unlike coming out of the closet, refusing to perform self-obscurity, taking responsibility to grow analytic muscle. Personally it has been difficult for me, but then when I arrive at a text like this interview, it takes me a few minutes of feeling insecure about my lack of expertise for not fully understanding the conversation, but then after reading it all i am relieved to know that its real substance resides in the last paragraph in which Khan openly installs his own frame over the conversation and it becomes crystal clear that, after all, the artist has been for sensing and making sense of the details all the way to the context. All of a sudden Khan proves once more that the network of indeterminacy that keeps us all under the reign of the dominant contemporary art is heavy, but not undefeatable.

Mohammad: Are we being too generous here? I think there are a lot of amazing nuggets all over the interview and since we don’t have a lot of space, before we concentrate on the concluding paragraph, there is one instance which I think beg some reflections. I am addressing the part about corruption in Italy and how this corruption puts Khan at ease.

Sam: Probably I am too afraid of making obscure statements, but for sure there is a lot of inspiring material there. To be honest, I am am trying to avoid the subject of corruption especially when it is about Egypt and Italy as I sit in my studio in Amsterdam. I can secretly relate to him regarding the similarity between Italy and the Middle East in regards to corruption. However, this in itself needs elaboration to avoid misreadings because I hear similar Orientalist statements about Italy and the Middle East from people in northern Europe who are not familiar with the difference in complexities, in regards to corruption in the Egyptian and Italian contexts.

Mohammad: The issue of the place of public intellectuals is a very important one because it has a lot to do with Khan taking comfort with respect to corruption in Italy. I think we can probably make some correlation here between the spectrum of corruption and the relevance of the public intellectual to the political and social direction of a given society. Also there is something to be said about the intensity of open and obvious corruption in a given society and its correlation to the level of press freedoms and freedom of expression in that society in general. The third correlation is of course about the correlation between freedom of expression and the significance of public intellectuals in a given society and how in this context, the public intellectual erroneously embodies the triumph of a particular intellectual or a group of intellectuals by becoming respected and well known, despite the political and social barriers set up for them by the state. In such societies intellectuals as Khan rightly asserts, are a major co-factor in its intensification, compensating with their intellect whatever is missing due to repression. It is also wrongly assumed that a society which enjoys freedom of expression and independent scientific research from church and state may no longer need the guiding light of its intellectuals.

Sam: This is true but there is also another side to this, which is those cases in which a form of good corruption or what I call the corruption of the corruption is exercised by its public intellectuals. I can’t help but think about the example of Saadi in Golistan, about the judicious lie versus the seditious truth. In short, a despotic king wants to execute a man who happens to not be a Persian speaker. As he realizes he is going to be killed he starts to curse and swear at the king. The king asks one of his ministers about the meaning of the convict’s words. In order to save the person’s life, the minister lies, saying he is praying for the life and well being of the majesty. The surprised king ends up forgiving the poor man. Meanwhile a saboteur minister tells the truth to the king. Surprisingly, the king blames the truth-telling minister rather than the lying one, shaming him for his supposedly good deed that nevertheless was going to cost one’s life, the moral conclusion of the story being that there are cases in which one ought to favor the judicious lie over the seditious truth. The story can also be an example of the differential ethics and therefore aesthetics in an imperial worldview that later informs that of the Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal empires. I think this is why such a sophisticated social game seems to be a plain corruption from the position of a puritanically constructed Western worldview which sees itself as a direct, honest and essentially non-corrupted or even corruptible society.

Sam Samiee is an Iranian Amsterdam-based painter and essayist, currently a resident artist in the two-year program at Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten.

Mohammad Salemy is an independent NYC/Vancouver-based critic and curator from Iran. Salemy holds an MA degree in Critical and Curatorial Studies from the University of British Columbia.