SUPERCONVERSATIONS DAY 48: JASON ADAMS RESPONDS TO KETI CHUKHROV, “WHY PRESERVE THE NAME ’HUMAN’?”

#Nothing Universal is Human To Me

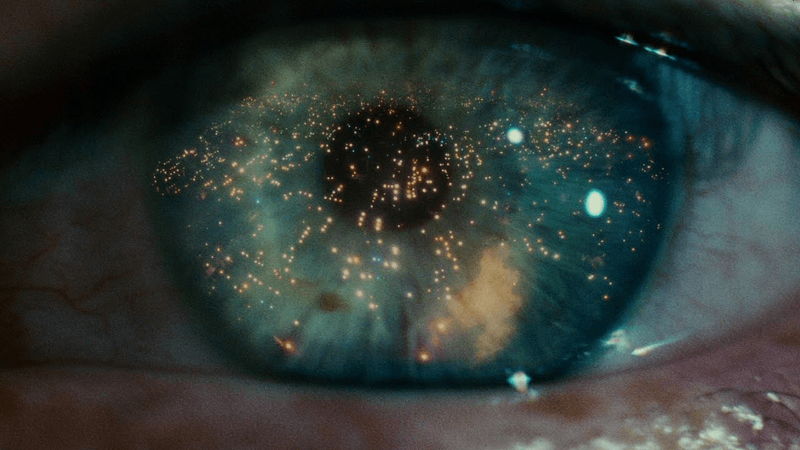

Still. Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982).

Whether it is presented in organic or technological form, the ontological juxtaposition of the human and the alien is one of the most commonly-repeated motifs in science fiction film: whether via good humans vs. evil aliens, or evil humans vs. good aliens, such films moralize geography as much as they securitize subjectivity. However, consider two exceptions: Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar and Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. In the former, the figure of the alien is always-already human, while in the latter, the figure of the human is always already-alien. While the two narrative choices might seem essentially interchangeable, there are important differences.

Keti Chukhrov’s contribution is best read as of the Interstellar type. She engages the figures of the alien and the human via an opposition between accelerationism, speculative realism, and object-oriented ontology on one hand, and Marxism, humanism, and cosmism on the other. The figure of the alien is placed on the former side in her narrative, while that of the human is ascribed to the latter. And, while Kant and Hegel are narrated as embracing the “inhumanness within humanness”, ACC/SR/OOO is said to posit alienation as something that must be endured beyond the human entirely, since the human is incapable of encountering the alien from within the human, as remains possible in Kant and Hegel.

Such a claim seems a strange one to attach to an assemblage of recent philosophical developments concerned specifically with rejecting correlationist assertions about what can and cannot be grasped by humans. Does Chukhrov mean to say, rather, that for ACC/SR/OOO, the noumenal is inaccessible to the phenomenal subject, which must rely instead, upon reason, mathematics, carbon-dating, and other abstractions? And if so, is this not also the case for Kant and Hegel? The fact that Reza Negerastani’s concept of the “inhuman”, (http://www.e-flux.com/journal/the-labor-of-the-inhuman-part-i-human/) for instance, supports neither Chukhrov’s rhetorical choice nor the distinction it is attached to, would seem to deepen the stakes of answering these queries properly.

Indeed, it may even be worth recalling here Kant’s assertion that the “terrestrial rational being” cannot be characterized in any ultimate manner due to humanity’s not having encountered “nonterrestrial rational beings” against which they could be compared, and thus defined in the first place. Pushing further, does it not follow that it is Blade Runner’s rather than Interstellar’s ontology that holds more strongly - in other words, that the human is itself best understood as the alien? And if the alien is that which belongs to the foreign rather than to one’s own subjectivity, shouldn’t scaling up to the most universal level possible make the ontology of alien-as-human impossible?

Even if a conventional neo-Kantian reader might well disagree, it would seem at least potentially to be the case for a modified, post-Kantian monism in which - as in all monisms - no second substance is admitted. Chukhrov’s neo-humanist account of cosmism as Spinozist, in contrast, frames it as a project of de-alienation, defined as the abolition of surplus value and the division of labor as much as the abolition of the conceptual/empirical and ideal/material distinctions. Cosmist neo-humanism, she suggests, rejects ACC/SR/OOO’s Blade Runner ontology - but doesn’t Chukhrov’s monism already imply that the human itself is a singularity amongst singularities, all of which derive from a single, decidedly non-human substance?

While many of those associated with ACC/SR/OOO might distance themselves from Spinozist approaches, a radical immanentism remains pervasive, one that, in several instances, appears as an endorsement not only for the usefulness of cosmism today, as in Robin Mackay and Armen Avenassian’s edited collection #Accelerate: The Accelerationist Reader or Nick Srnicek & Alex Williams’ forthcoming Inventing the Future, but also for precisely what Chukhrov disavows: radical immanentism as the ontological foundation par excellence for positing the human-as-alien.

As Ray Brassier put it in his dissertation, Alien Theory:

Man ‘is’ only insofar as he exists as a theoretical Stranger for Being and for the World. Hence our continuously reiterated emphasis… on Man’s radically inconsistent, non anthropological, and ultimately alien existence as the transcendental Subject of extra-terrestrial theory. Accordingly, were we to distill the substance… to a single claim it would be this: the more radical the instance of humanity, the more radically nonanthropomorphic and non-anthropocentric the possibilities of thought. By definitively emancipating Man’s theoretically alien, non-human existence, non-materialist theory promises to purge materialism of all vestiges of phenomenological anthropomorphism. It is this rediscovery of Man’s irrefrangibly alien existence as a universal Stranger that prevents non-philosophy’s gnostically inflected ‘hypertranscendentalism’ from merely reinstating Kant’s transcendental protectionism vis a vis man as Homo noumenon.

Chukhrov’s cosmist neo-humanism continues along the path paved by Interstellar’s ontological commitments: it anthropomorphizes and anthropocentrizes the human, such that any expression of thought anywhere else in the universe can only be understood as either the reappearance of the human in a new form or as the fulfilling of the human function in a non-human form that remains, however inexplicably, human. Like Chukhrov’s essay, Interstellar was a highly engaging experience, but in the end, it is Blade Runner that allows the fullest potential of the human to be expressed, that of the alien that it always-already has been.

Jason Adams is an organizer at The New Centre for Research & Practice and holds a PhD in Political Science from the University of Hawaii and a PhD in Media & Communication from the European Graduate School.