In this second contribution, I delve a little deeper into the question of totality and of totalization. In particular, I want to consider the popularity of ‘world literature’ as an academic, global-institutional and journalistic category that represents a significant contemporary claim to totality, one that perhaps leaves out as much as it includes. I’m in agreement with Alberto and Sarah that the problem of cognitive mapping, of ‘making it whole’ is, in large measure, a sublimation at the level of the aesthetic of the political production of scarcity, and of the relative absence of collective politics. But I’m sure they would agree that, despite this, the aesthetic is by no means uncomplicatedly subordinated to the political. Further, real abstraction in its various guises guarantees the emergence of concrete effects from domains – and the ‘aesthetic’ is surely not quite the right term – that might otherwise be considered non-material, sociologically impenetrable, resistantly interior. What are the inadequacies, I will ask, of one of the most reified of the frameworks by which we think totality today, at the level of disciplines and institutions imbricated in the world market. I’ll also briefly assay a model of globality that may, if we’re lucky, offer more critical purchase. But just as the ‘aesthetic’ is by no means a world unto itself, so I will need to associatively trace in passing the ways in which ‘totality’ gives out promiscuously onto notions of totalization, of form, and of formalization. The broader hope is that, instead of announcing a mere retreat from politics, a renewed attention to totality and totalization, to form and formalization, across art, literature, politics and philosophy, may be just one way in which critical theory becomes critical again.

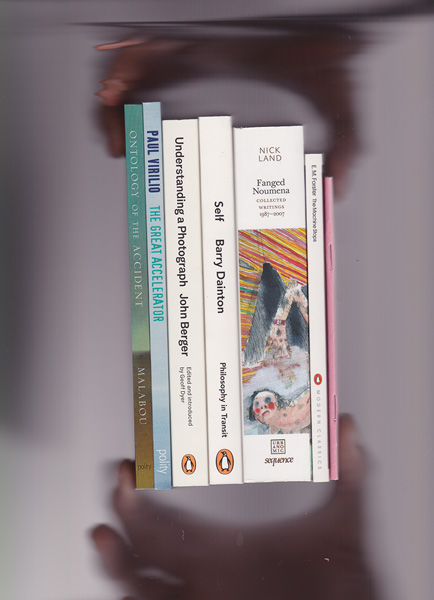

‘World Literature’, then, has become something of a rallying cry in the literary and critical humanities. While the move to broaden the geographical scope of literary and cultural study has been fulsomely welcomed in some quarters, others have questioned the haste with which scholars have been enjoined to engage literatures written in languages they do not master, and ensconced within cultures of which they know little. Emily Apter has been one of the more visible critics. For her, the category of world literature tends toward “reflexive endorsement of cultural equivalence and substitutability, or toward the celebration of nationally and ethnically branded ‘differences”. (‘Against World Literature’, Verso 2013, 2). Such criticism rests on an allied and more explicitly political fear that the call for ever-more inclusion is, in fact, the mere extension of a commodifying and neutralizing drive of a part with the stultifying omnipresence of the world market. Such literatures as may now be admitted to the canon (or canons) begin to resemble, according to such a critique, tastefully exotic baubles to be collected by scholars, the better to embellish their claims to cosmopolitanism.

https://joshuamcdonnell.files.wordpress.com/2012/02/hands-holding-earth.jpg

At base, these concerns pertain to the model of totality and totalization that world literature as a new disciplinary and institutional configuration would seem to reproduce. It is not, that is, the desire to approach the limits of what is knowable in literature, art or politics that is to be rejected; it is certainly not, even more, the desire in and of itself to totalize that is at issue. Rather, it is the particular vision of totality employed that raises crucial questions. The following from David Damrosch is exemplary:

“A central argument of this book will be that, properly understood, world literature is not at all fated to disintegrate into the conflicting multiplicity of separate national traditions; nor, on the other hand, need it be swallowed up in the white noise that Janet Abu-Lughod has called “global babble.” My claim is that world literature is not an infinite, ungraspable canon of works but rather a mode of circulation and of reading, a mode that is as applicable to individual works as to bodies of material, available for reading established classics and new discoveries alike.” (‘What is World Literature?’, Princeton University Press 2003, 5).

The idea of ‘circulation’ is used here to offset any impression that world literature may only be capable of an extreme cultural particularism on the one hand, or a bland homogenization on the other, the latter dichotomy a more general version of that between rigidly national literatures at one end of the spectrum, the dissolving of the national into the worldly on the other. Indeed, the trope of circulation, displaced here from its more usual habitat in Marxist criticism, is now an identifying motif for the field of world literature per se; Franco Moretti is surely the pioneer here. To induce a sense of circulation is to suggest the puncturing of any airless totality, any static vision of a world whose boundaries would be easily and unproblematically delineable. The opposite of this airless totality would be the single, particular text, imagined as an interiority containing multitudes, this latter dichotomy (text/world) at least partially metonymic of the world/nation dyad already mentioned. As Moretti has it, using Wallerstein’s world-systems theory as a model, world literature proper would reject both sides of this self-confirming duo: “The text which is strictly Wallerstein’s…occupies one third of a page…the rest are quotations…Now, if we take this model seriously, the study of world literature will somehow have to reproduce this ‘page’…literary history will quickly become very different what it is now: it will become ‘second hand’: a patchwork of other people’s research, without a single direct textual reading”. (‘Conjectures on World Literature’, New Left Review 1, 2000, 57).

The ‘other people’s research’ in question would be the spatially and temporally broad range content analysis enabled by computation, by the now much-vaunted ‘digital humanities’. Cultural objects, on such a vision, could be seen to circulate, to intermingle, to distance themselves, thus to never settle into anything approaching a rigid ‘world’, just as much as their particular content – the self-enclosed modulations of the individual book or sentence – would fade from relevance. Two totalities are rejected here, or so it seems: the world as a finally delimitable totality, and the individual text as lure to the rabbit holes of close reading. But just as important to detect in such a rejection is the exclusion of the nation/world antinomy itself, Moretti wishing to avoid the mere obverse of what have, in disciplinary terms, been parceled out as so many nationally specific literatures and languages.

Damrosch’s and Moretti’s visions are not entirely equivalent, of course; Damrosch, for instance, seems much more at ease with the full semantic weight of the term ‘world’, its indication of a provisional planetary fixity, where Moretti would rather wish to perpetually reset such a putative boundary according to the particular digital-historical analysis in question. Moretti, characteristically, would place his bets on the glittering promises of ever-new methodologies as a means of upsetting theoretical rigidity. But both Moretti and Damrosch rely upon the trope of circulation, as already mentioned, and we can surely only come to understand such a notion, such a suspiciously graceful ballet of perpetual literary movement, according to an implied border or limit as its necessary other, a limit within which, even against which, such entangled movements become visible. To foreground circulation per se is to risk positing movement as its own justification, against any more critical questioning of the arena within which such movements are tacitly assumed to take place, or the model of totality that this valorization of motion otherwise presupposes. Refocusing our attention onto the arena itself, or the implied totality inherent in the worlding of the ‘world’, to abuse Heidegger, may then lead us to propose alternative models of totality or totalization, models attentive to the uneven conditions of belonging, exclusion, visibility and hiddenness that are the material and abstract conditions of modern cultural production and reception.

Where to go from here? In his suggestive essay ‘How Do We Recognize Strong Critique?’ , the philosopher Paul Livingston rehearses various ways of thinking formal wholes and their limits. He does so in order to re-dynamize our understanding of form and formalism; he is especially attentive to the ways in which these have operated hitherto in the domains of formal logic and mathematical theory. The latter have, for Livingston, promising things to say to spheres of action and critique otherwise apparently severed from them, most notably radical political theory. I will be unable to do full justice to his philosophical originality in this concluding reflection; instead, I will reappropriate and reconfigure just a few of the conceptual resources he offers as a means of thinking anew the potential of totality as both figure and imperative.

What does Livingston mean by ‘strong critique’? “To indicate”, Livingston writes, “the formal structure of strong critique”, “it suffices…to discern the fundamental orientations of thought which unfold the formal ideas of completeness, consistency and reflexivity as they structure the configurations in which the real of being gives itself to thought”. (‘How Do We Recognize Strong Critique?’, Crisis and Critique 3, 2014, available online: http://materializmidialektik.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/liv.pdf).

‘The real of being’: there’s no shortage of ambition here, Livingston intending to signal how a focus on different kinds of formal limitation – in our terms, those instances when the process of worldly totalization meets a limit that, when viewed from a certain angle, is appreciable as its constitutive ground – may give us access even to a kind of ontological truth.

But leaving aside Livingston’s ontological ambitions – I am less convinced that ontology may be so decisively rid of its distracting metaphysical baggage - how might his models benefit a critical approach to the problem of world as totality? For Livingston, any assessment of a totalizing model must attend to its ideas of ‘completeness, consistency and reflexivity’. In other words, models of totality may be more or less committed to a sense of completeness or closure, may be more or less convinced as to their lack of fissures, and may be more or less willing to admit their own partiality, mutability – the reflexive and changeable conditions under which they emerged. Measured up to these standards, the ‘world’ in ‘world literature’ is, I think, too often assumed to be more or less even, more or less complete; is too frequently assumed to be legible at each of its levels, and thus without symptomatic blindspots or zones of inconsistency or problematic limits; is too infrequently reflexive about the scholarly, institutional and theoretical conditions that make it such an attractive rubric in the first place.

How to model the world critically? Livingston insists that any critical map of totality must insist on ‘the inherence of contradiction’. This is not simply to acknowledge the existence of aspects of the totality that don’t really fit, that aren’t productively ‘read’ by data mining or positivist social science; rather, it is to argue that such aspects are, very often, the very hidden condition of possibility for the apparent durability of the totality per se. When translated into broadly Marxist terms, such constitutive round pegs in square holes would include those populations excluded from the middle-class measures of taste that produce a notion of literature that may then be productively ‘globalized’. They would surely involve the sources of the vast amounts of cultural capital appropriated and resold from areas of the world with uneven access to networks of prestige. And they would involve the particular subjective uses that are made of literary meaning, so often in contradiction with the generalizing rubrics with which literary artifacts are circulated and objectively ‘appreciated’. (This is to say that Moretti’s rejection of ‘close reading’ is hasty indeed).

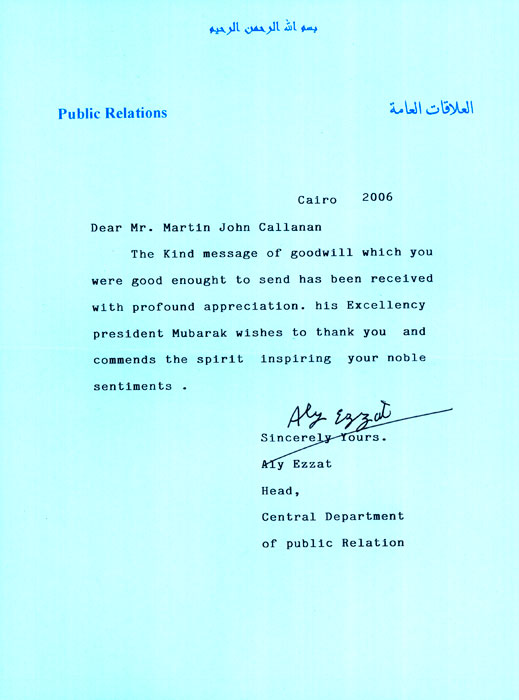

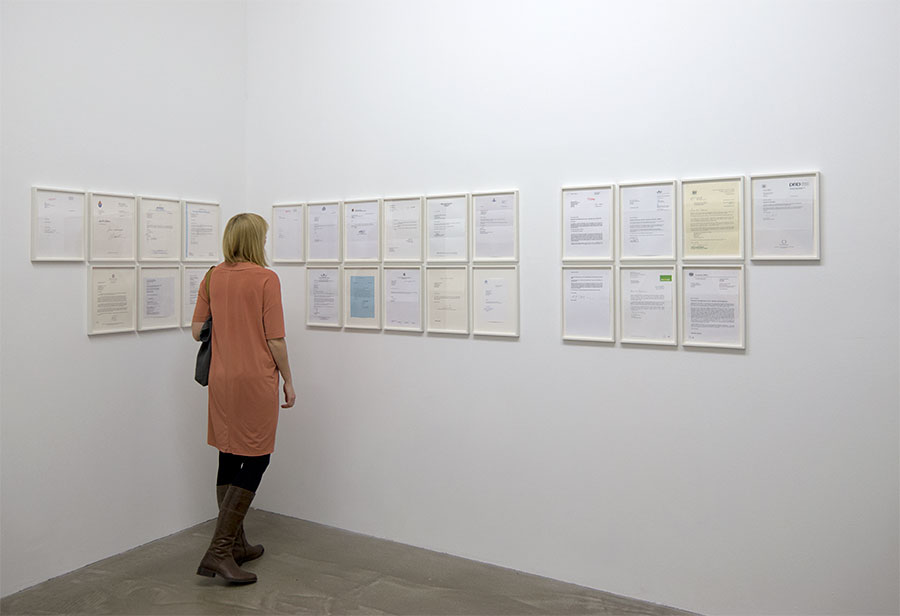

The reader will surely be able to think of many more. The point is to appreciate the strict necessity of such included-exceptions to the survival of the totality in question. A skeptic would surely respond: ‘but there are numerous scholarly volumes that uncover cultural zones otherwise hidden to the world market’. This is no doubt true, but there is a difference between a methodological commitment to ‘recovering’ underread or hidden texts, and a theoretical acknowledgement of the paradoxes of our various totalities insofar as they may require the analytical forgetting of such sources. By foregrounding such conditions, one is not beholden to abandon the concept of totality, but is rather enjoined to think it through to its constitutive limits.

My point is just that it is characteristic of the contemporary media landscape that the divide between consumer cultural production and the literary sphere is hard to maintain, and the name of the writer as the source of the original creativity protected by copyright both asserts the commodity’s distinction from regular goods and helps to generate demand for further goods.

My point is just that it is characteristic of the contemporary media landscape that the divide between consumer cultural production and the literary sphere is hard to maintain, and the name of the writer as the source of the original creativity protected by copyright both asserts the commodity’s distinction from regular goods and helps to generate demand for further goods.