For Commentary Magazine, Michael J. Lewis has written about how art has become irrelevant. An excerpt below, the full piece here.

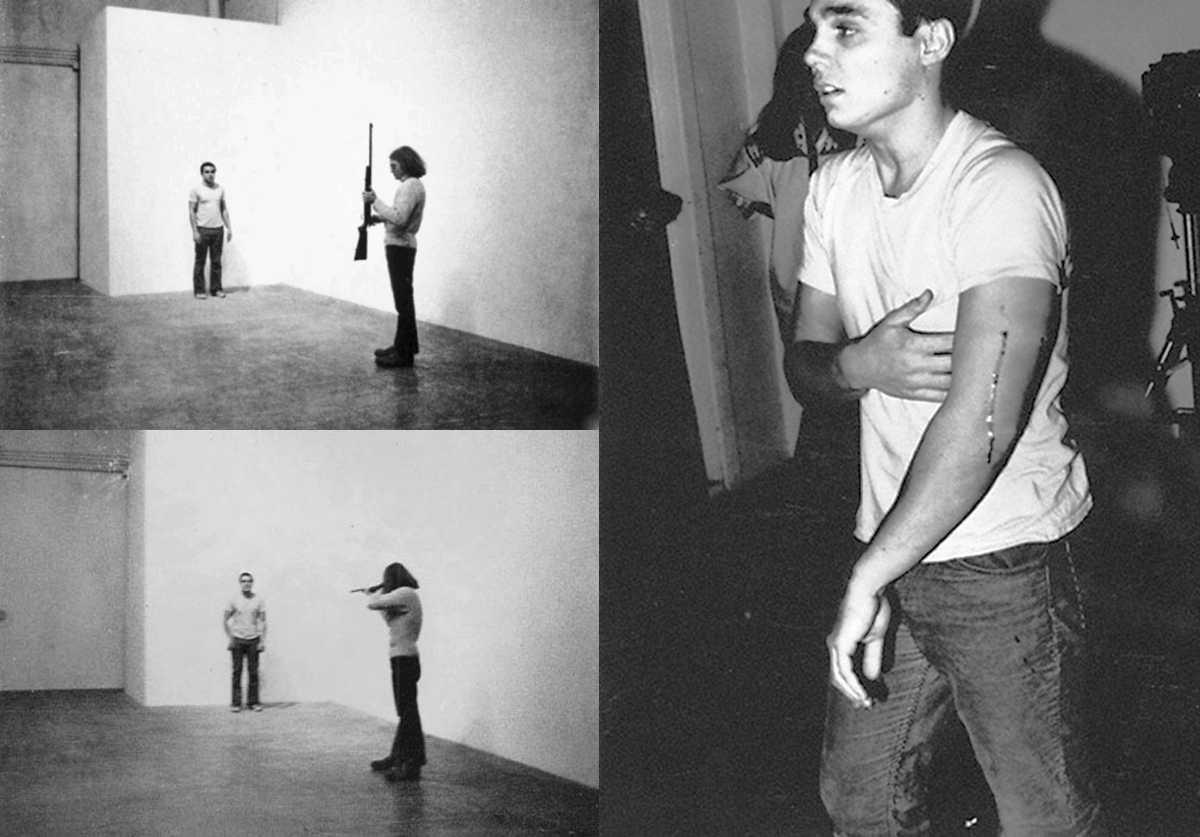

In 1971 the performance artist Chris Burden stood against the wall of a California art gallery and ordered a friend to shoot him through the arm. That .22 rifle shot was the opening salvo of a movement that came to be called “endurance art”—an unnerving species of performance art in which the performer deliberately subjects himself to pain, deprivation, or extreme tedium. Try as he might, Burden never quite matched the shock of his spectacular debut (and he did try, once letting himself be crucified onto the back of a Volkswagen Beetle).

As fate would have it, I had just shown my students at Williams College the grainy footage of Burden’s shooting when we learned of his death in May. Curiously, the clip did not provoke them as it had their predecessors in my classrooms in decades past. No one expressed any palpable sense of shock or revulsion, let alone the idea that the proper response to the violation of a taboo is honest outrage. One student fretted about the legal liability of the shooter; another intelligently placed the work in historical context and related it to anxiety over the Vietnam War.

Placing things in context is what contemporary students do best. What they do not do is judge. Instead there was the same frozen polite reserve one observes in the faces of those attending an unfamiliar religious service—the expression that says, I have no say in this. This refusal to judge or take offense can be taken as a positive sign, suggesting tolerance and broadmindedness.

But there is a broadmindedness so roomy that it is indistinguishable from indifference, and it is lethal. For while the fine arts can survive a hostile or ignorant public, or even a fanatically prudish one, they cannot long survive an indifferent one. And that is the nature of the present Western response to art, visual and otherwise: indifference.

In terms of quantifiable data—prices spent on paintings and photographs and sculptures, visitors accommodated and funds raised and square footage created at museums—the picture could hardly be rosier. On May 1, New York’s Whitney Museum moved from 75th Street to the Meatpacking District and reopened in a $422 million building. The move first seemed inexplicable when it was announced several years ago, but it has proved to be a brilliant stroke. Relocating to a hotter and more fashionable neighborhood abutting the wildly popular High Line Park is one of those gambits that instantly transforms the logic of the game board, like castling in chess. The new Whitney was designed by the furiously prolific Renzo Piano, and while it will not please everyone (its boxy swivel of platforms distressingly recalls the flight tower of an aircraft carrier), it swaggers with brio and panache and is fast becoming one of the world’s best-attended museums.

Equally robust is the art market, to judge by a Christie’s auction on May 11 that set several records, including the highest price ever paid at auction for a work of art: $179.4 million, paid by an anonymous bidder, for Picasso’s Women of Algiers (Version O). One can expect more such record-breaking in the next few years as the art market is increasingly roiled by Hong Kong dollars, Swiss francs, and Qatari riyals. (The buyer of the Picasso was subsequently revealed to be the former prime minister of Qatar.)

But quantifiable data can only describe the fiscal health of the fine arts, not their cultural health. Here the picture is not so rosy. A basic familiarity with the ideas of the leading artists and architects is no longer part of the essential cultural equipment of an informed citizen. Fifty years ago, educated people could be expected to identify the likes of Saul Bellow, Buckminster Fuller, and Jackson Pollock. Today one is expected to know about the human genome and the debate over global warming, but nobody is thought ignorant for being unable to identify the architect of the Freedom Tower or name a single winner of the Tate Prize (let alone remember the name of the most recent winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature).

The last time that artists were part of the national conversation was a generation ago, in 1990. This was the year of the NEA Four, artists whose grants were withdrawn by the National Endowment for the Arts because of the obscene content of their work. Their names were Tim Miller, John Fleck, Holly Hughes, and Karen Finley—the latter especially famous because her most notable work largely involved smearing her own body with chocolate. As it happened, their work was rather less offensive than that of Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe, who had been the subject of NEA-funded exhibitions the year before. Serrano’s photograph of a crucifix immersed in a jar of his own urine was called “Piss Christ.” Mapplethorpe’s notorious self-portrait featured a bullwhip thrust into his fundamental aperture. Even the New York Times, a stalwart champion of Mapplethorpe, could not honestly describe that photograph, let alone publish it, referring to it with coy primness as a “sadomasochistic self-portrait (nearly naked, with bullwhip).”

That controversy ended with a double defeat. In a case that was heard by the Supreme Court, the NEA Four failed to have their grants restored. But Senator Jesse Helms and Representative Newt Gingrich likewise failed in their determined effort to defund the NEA (total budget at the time: $165 million). And the American public—left with an impressionistic vision in which urine, bullwhips, and a naked but chocolate-streaked Karen Finley figured largely—drew the fatal conclusion that contemporary art had nothing to offer them. Fatal, because the moment the public disengages itself collectively from art, even to refrain from criticizing it, art becomes irrelevant.

This essay proposes that such a disengagement has already taken place, and that its consequences are dire. The fine arts and the performing arts have indeed ceased to matter in Western culture, other than in honorific or pecuniary terms, and they no longer shape in meaningful ways our image of ourselves or define our collective values. This collapse in the prestige and consequence of art is the central cultural phenomenon of our day.

It began a century ago.

For most of human history, works of visual art were the direct expression of the society that made them. The artist was not an autonomous creator; he worked at the behest of his patron, making objects that expressed in visible form that patron’s beliefs and aspirations. As society changed, its chief patrons changed—from medieval bishop to absolutist despot to captain of industry—and art changed along with it. Such is patronage, the mechanism by which the hopes, values, and fears of a society make themselves visible in art. When World War I broke out in 1914, that mechanism was delivered a blow from which it never quite recovered. If human experience is the raw material of art, here was material aplenty but of the sort that few patrons would choose to look upon.

When I went to Germany to study architecture in 1980, it was still common to see wounded veterans from both world wars. The first seats on buses or subways were reserved for them and were usually occupied. One day a fellow student and fellow history buff chanced to remark that the worst cases were from World War I, but of course one never saw them.

“They never show their faces?” I asked, naively.

“Mike,” he said, “they have no faces to show.”

He was speaking of the Verstümmelten—the mutilated, those who lost jaws, cheeks, and noses in the shambles of the trenches, where a raised head was the target of choice. They had been so wounded, brought to a nearby field lazaretto and put together as much as possible, that they would spend the rest of their lives seen only by the family members who tended to them. “There is one,” my friend said—I can still picture the expansive gesture he made—“in practically every street.”

Not until then did I properly grasp the unbearable intensity of German artists such as Ernst Kirchner, Otto Dix, and George Grosz, who created their most memorable work during the war or just afterward. The human body—dynamic, beautiful, created in God’s image—had long been the central subject of Western art. It was now depicted in the most tormented and fragmented manner, every coil of innards laid bare with obscenely morbid imagination. Kirchner and Dix depicted the gore. Grosz, who refrained from showing actual injuries, was even more disturbing. He made collages of faces out of awkwardly assembled parts, like a jigsaw puzzle assembled with the wrong pieces, suggesting those sad prosthetics that would have been an ubiquitous presence in 1918.

Christianity had introduced the motif of beautiful suffering, in which even the most agonizing of deaths could be shown to have a tragic dignity. But things had now been done to the human body that were unprecedented, and on an unprecedented scale. The cruel savagery of this art can be understood only as the product of collective trauma, like the babble of absurd free associations that tumble from our mouths when in a state of shock. That kind of irrational expression was the guiding principle of Dada, the movement that came about at the end of the war and that was made famous by Marcel Duchamp’s celebrated urinal turned upside down and named Fountain. Even the name Dada itself was a quintessential absurdist performance, selected at random from a French-German dictionary (the word is French baby talk for “hobby-horse”).

Dada applied unserious means to a serious end: the search for an artistic language capable of expressing the monstrous scale and nature of the war. But the absurdist moment was short-lived and quickly superseded. The toppling of Europe’s three principal empires and the Russian Revolution seemed to confirm that the West had entered into a radical new phase of cultural history, the most consequential since the rise of Renaissance humanism half a millennium ago. There was a general sense that a world radically transformed by war required an equally radical new art—an art of urgent gravity. While modern art had certainly existed before the war, there now came into being a comprehensive “modern movement” that was active in all spheres of human action, not only in art but in politics and science as well. In its wake, Pablo Picasso rose from being a mere painter with a quirky personal style to a world-historical figure whose work was as important to the future of mankind as Einstein’s or Freud’s.

All this gave the modernism of the 1920s its tone of moral seriousness, which became even more serious once the Great Depression began. One sees this high-minded seriousness most strikingly in the architects of the modern movement. They saw their mandate as the solving of the central architectural challenge of modern life—how to use new materials and means of construction to make housing affordable and cities humane. Today the lofty principles that motivated them seem quaint, such as that German fixation on the Existenzminimum. This was the notion that in the design of housing, one must first precisely calculate the absolute minimum of necessary space (the acceptable clearance between sink and stove, between bed and dresser, etc.), derive a floor plan from those calculations, and then build as many units as possible. One could not add a single inch of grace room, for once that inch was multiplied through a thousand apartments, a family would be deprived of a decent dwelling. So went the moral logic.

We may shudder at the thought of so many identical families penned into so many identical boxes, but at root this idea was an expression of a humane and humanistic view of the world. It took for granted that the mission of architecture was to improve the human condition, even as modern artists assumed that theirs was to express that condition. To accomplish this, they did not require the traditional patron. The prestige and power of those patrons had been diminished by the war, and with that diminution went their ability to dictate to artists. That became even more pronounced after the stock-market collapse in the late 1920s, especially in the United States. When the Museum of Modern Art introduced European modern architecture to America in its celebrated 1932 exhibition of the International Style, it dismissed the traditional capitalist client with remarkable highhandedness. A half century of robust artistic and architectural patronage by the industrialists who had ruled American life since the Gilded Age was written off with a sneer by the exhibition’s organizer, Alfred Barr: “We are asked to take seriously the architectural taste of real-estate speculators, renting agents, and mortgage brokers.” In other words, the making of art was far too serious to be left to sentimental clients who might mistakenly desire a narrative painting with a clear moral message, or a facsimile of a villa they had admired in Tuscany.

After World War II and the introduction of the atom bomb, it seemed pointless to try to preserve the confused traditions of a civilization that had brought the world to the ledge of oblivion. Instead, the artists came to believe they had to dispense with the entire accumulated storehouse of artistic memory and the history of the benighted West in order to begin anew.

The 1950s painter Barnett Newman summarized this line of thought pretentiously but accurately:

We are freeing ourselves of the impediments of memory, association, nostalgia, legend, myth, or what have you, that have been the devices of western European painting. Instead of making “cathedrals” out of Christ, man, or “life,” we are making it out of ourselves, out of our own feelings.

*Image of Chris Burden, “Shoot” via OpenCulture