This text was originally presented by the author at State of Emergency: Politics, Aesthetics, Trumpism, a public forum that took place at New York University on December 10, 2016. Over the coming weeks e-flux conversations will publish more texts and videos from this forum.

Text by Hal Foster

Sure, “post-truth” is a big problem, but what about “post-shame”? How to challenge a politician who cannot be embarrassed? Or to protest a leader who thrives on the absurd? How to out-dada a dada president? Maybe, when they go very low, we should go even lower, and aim to outrage the outrageous…

Thoughts about a post-shame condition lead to stories about a pre-shame time. The most outrageous of these projections concerns “the primal father.” You remember that, in Totem and Taboo (1913), Freud derives the figure from “the primal horde” in Darwin, a great band of brothers ruled over by an all-powerful patriarch. This awful father enjoys all the women in the horde (that is the only role women have in this wacky tale), and leaves the brothers out sexually, to the point where they rise up, kill, and devour the tyrant. Yet this act plunges them into deep guilt (it is the first time it is felt), and so they elevate the dead father again, now as a god, or at least a totem around which taboos are established (the taboos against murder and incest above all). Thus, for Freud, does society begin.

There is a way to read this fable of prehistory historically, as a gloss on the bourgeois revolutions that overturned the kings, that is, as an allegory of democracy, “the transformation of the paternal horde,” as Freud puts it, “into a community of brothers.”¹ He brings back the primal father several years later in Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (1921), and if Totem and Taboo reflects indirectly on democracy, Group Psychology does the same with fascism—that is, with the return, long after the democratic decapitation of the king, of the dictatorial egocrat. In fact for Freud the mass politics of the time induces a regression to “the group psychology of the horde.” “What is thus awakened,” he writes, “is the idea of a paramount and dangerous personality towards whom only a passive-masochistic attitude is possible.” “The leader of the group,” Freud concludes, “is still the dreaded primal father; the group still wishes to be governed by unrestricted force; it has an extreme passion for authority…”²

Why recall the primal father in relation to Trump? Of course it is hazardous to psychologize anyone, let alone millions of voters, to totalize them in this way, but there is a psychic dimension to his support that we have to probe. No doubt many of his voters—and remember that he received 63 percent of the white male vote—are sexist and racist, whether secretly or not; certainly most were angry at elites too. But they were also—they were primarily—excited by Trump, excited to vote for him: there was positive passion, not only negative resentment. It is difficult for most of us to see why, but one way is to suggest that he tapped into “the erotic tie” that binds the horde to the primal father.³ For this figure both embodies the law (he lords it over the brothers) and performs its transgression (he can grope any woman). A potent double-identification opens up: the brothers submit to the father as authority and envy him as outlaw. And so we have a celebrity president (“when you’re a star…you can do anything”) as throwback primal father (or maybe just bully-in-chief), and there are legions of white guys who want to be his “apprentices.”

x

¹ Sigmund Freud, Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego, trans. James Strachey (New York: W.W. Norton, 1959), 54.

² Ibid., 59.

³ Of course my semi-facetious micro-analysis leaves out a huge piece of the electoral puzzle—why it is that a majority of white women would vote for Trump too.

Top image: Francis Picabia, L’Adoration du veau (The Adoration of the Calf), 1941–42

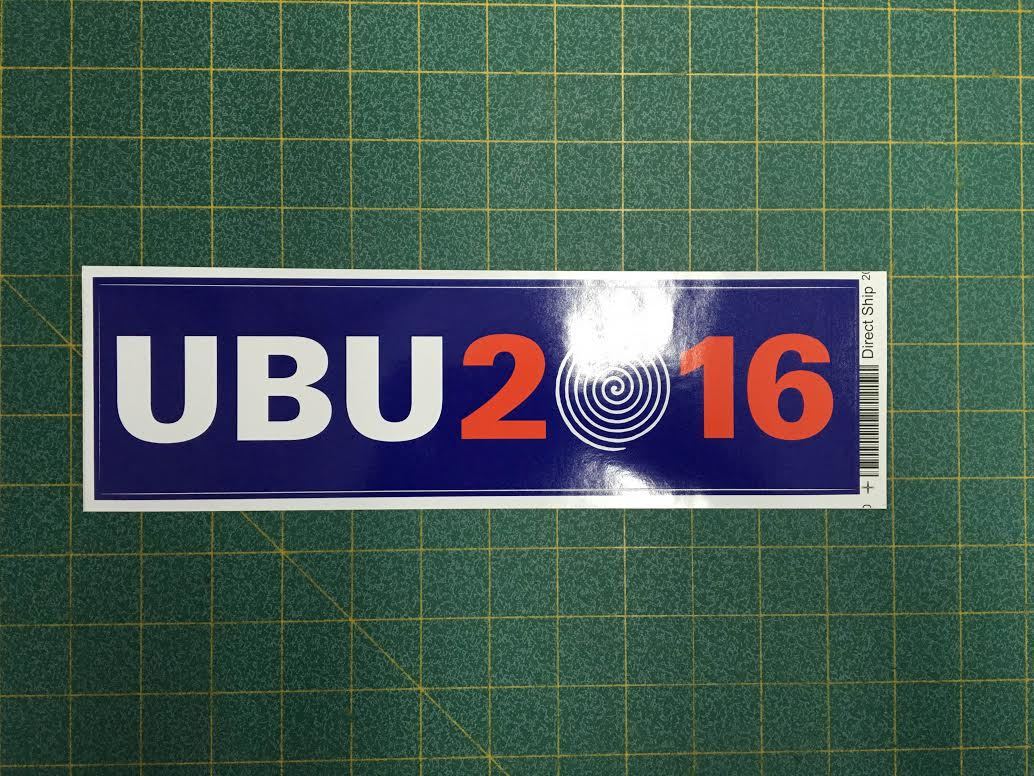

Lower image by Richard Massey.