Gregory Sholette, one of the #J20 art strike call’s signatories, responds to Jonathan Jones’s article “The ‘art strike’ against Trump is futile–cultural elites cannot effect change,” published in The Guardian, January 9, 2017.

Such a record number of people visited the Tate Modern last June that the museum removed the two Brazilian macaws included in Hélio Oiticica’s installation fearing that the animals’ health may be at risk. In another testament to art museum popularity, the Metropolitan Museum of Art clocked over 6.7 million visitors in 2016. And within the art market, according to the Dublin-based organization Arts Economics, total global art sales reached 63.8 billion USD in 2015. Add to this both the remarkable explosion of museums in China and the desire by countries such as Abu Dhabi and Dubai to obtain institutional art brands such as the Louvre and Guggenheim, and ask yourself whether one can really claim straight-faced—as Jonathan Jones has—that a call for American artists to strike on inauguration day is “nostalgic” and “futile”?

Yes, shutting down reality television programming would undoubtedly affect more people than an art strike, as Jones suggests—who could disagree with that? And yet, by simply running the numbers we can see the potential power of high culture. One need not be familiar with sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s studies linking actual power with accumulated cultural and social capital, including art collecting, to grasp the ideological authority of art. The president elect’s inaugural planners have recently stirred controversy by seeking to borrow from the St. Louis Art Museum an oil painting by George Caleb Bingham entitled “Verdict of the People.” The work depicts the reading of election results in mid-19th century America and will become the backdrop to the new president’s luncheon following his swearing-in ceremony if a petition rejecting the loan now underway does not succeed. (See Hrag Vartanian’s report via Hyperallergic here.)

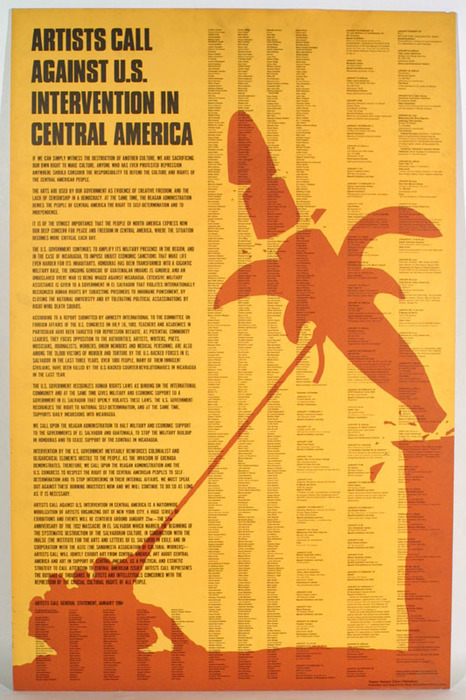

Just as important as the impact of art is artists’ grassroots organizing that accomplishes political and social justice. Such mobilization has the ability to generate discussion as much as disagreement, and it frequently leads to longer-term coalition building. Neither is such activism merely the parroting of 1960s cultural protests as Jones insists. Even a cursory reflection on the tactics of activist artist coalitions such as the Guerrilla Girls (1985–ongoing), Gran Fury (1988–1995), A Day Without Art/Visual AIDS (1989–ongoing), Liberate Tate, and Gulf Labor Coalition (2010–ongoing), offers evidence that artists’ groups have continuously formed over the decades, and that they have often used cultural boycotts to amplify their objectives. Curiously, in a different Guardian piece, Jones acknowledges that the history of politically engaged art reaches back at least a century when he describes a Royal Academy exhibition featuring revolutionary Russian art as one of the great and “unmissable” cultural events of 2017. Nor is “art strike” the only such organization of culture that has taken place since the election, more examples of which can be found here.

Finally, it is simply not true that the signatories of the initial call for an art strike are “well-heeled” members of the “cultural elite.” Writing as one of the signatories, but also as a long-term art activist, I feel Mr. Jones’s description of the January 20th art strike as “shallow radical posturing,” is either poorly researched or intentionally hyperbolic, and frankly defeatist. If art is as minor and ineffectual as he suggests, and if orchestrating solidarity is as insignificant as he proposes, perhaps he is laboring at the wrong profession.

–Gregory Sholette, January 9, 2017

No Work, No School, No Business.

Museums. Galleries. Theaters. Concert Halls. Studios. Nonprofits. Art Schools.

Close For The Day.

Hit The Streets. Bring Your Friends. Fight Back.

For more information see the art strike announcement here.

*Top image: Russians queue for hours in freezing weather to visit the Valentin Serov exhibition at the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, on January 22, 2016 (AFP Photo/Vasily Maximov via Yahoo)