Commercial ventures whose success depends upon the generation of money, art fairs exist to sell art. They're not venues for exciting site-specific projects, spaces in which radical ideas can be exchanged, or interstitial zones where the everyday is overturned and the perennial passive spectator 'activated'. At least, that's how it used to be.

With the steady addition of talks programmes, site-specific projects, performances and new commissions, art fairs have become somewhat confused locations that increasingly mix commerce with creativity, cash with critique.

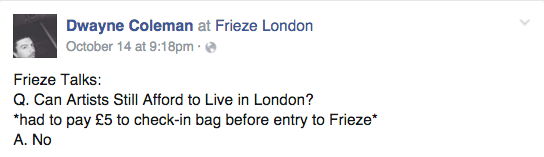

But at this year’s Frieze art fair in London a programmed talk titled ‘Off Centre: Can Artists Still Afford to Live in London’ tipped the uneasy balance between finance and art to a position that felt entirely more exploitative, offensive and grotesque. Put simply, the instrumentalisation and commodification of hardship took things a step too far.

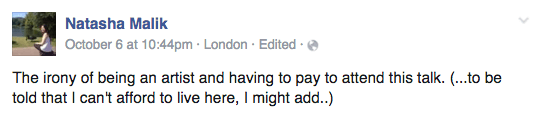

Can artists still afford to live in London? Of course not, nobody can. What made this public exercise even more absurd was the notion that a trade fair costing just under £40 (approximately $62) to enter, with an additional £5 (approximately $8) cloakroom charge for anyone carrying anything more substantial than a clutch bag or an iPhone, was the right place to do it.

Usually this kind of activity – the yoking of neoliberal capitalism and contemporary art of which Frieze represents a kind of summit – is dismissed with specious arguments, ‘it’s all part of the game’ eye-rolls and shrugs of resignation. But is it time to say enough is enough?

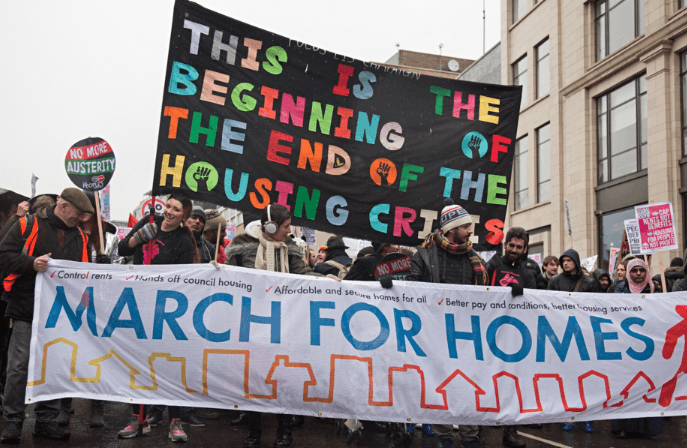

The difference now is that London is dying. It is a city being bled dry by David Cameron’s Conservative government for the benefit of moneyed elites, the same moneyed elites who push wealth between themselves under florescent bulbs inside Frieze’s stale, airless tent.

Of course, people are free to pursue and make money, there’s nothing inherently wrong with that. But is there something morally and fundamentally wrong about using critical engagement with politics, culture, society and economic hardship (i.e. the content of contemporary art since the 1960s) to provide trade fairs with that added bit of ‘cultural capital’ so that money moves around easily? Is there something base about using the human fallout that comes from the pursuit of capital to excuse and make the pursuit of capital more attractive?

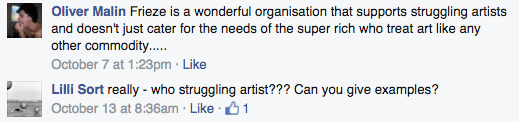

Many have voiced contempt for what this public talk has foregrounded, but surprisingly, in the past few days, I’ve come across artists and arts professionals who have explained away the patronage and exploitation ‘Can Artists Still Afford…’ represented, with a jaded, ‘worldly’ fatalism. They seem unfazed by the fact Frieze might have a part to play (however marginal) in the transformation of London from a multicultural metropolis to a landscape of high rise buildings containing empty ‘luxury flats’.

Again, the human fallout from these alterations and the relentless spread of alienating neoliberal practices throughout the capital are what makes this all difficult to stomach. But the fact that it is easy for others to swallow makes me think that there are, at present, two consciousnesses operating in the British art world: one that is happy to ignore the art world’s possible complicity with the wretched socio-cultural, economic and political state of things and another that finds it distressing, disturbing and debilitating to do so. What do you think?

Was misery monetized?

Is it time to walk away from Frieze?

Have you ever felt conflicted or compromised by capital? Was it okay because ‘all money is dirty’ and you ‘need to eat’?

Are Frieze projects, talks & commissions exciting opportunities or exercises in building ‘brand awareness’ and ‘encouraging investment’?

Are you ‘confused and disappointed’ that Tania Bruguera’s only appearance in London was at a commercial fair?

Can you afford to live in London?

Can you afford to live?