In the summer issue of Bookforum, Christian Lorentzen reflects on how our age of ubiquitous surveillance and compulsory self-disclosure has affected the meaning of secrets in literary fiction. As Lorentzen notes, “Secrets in conventional novels are the engines of plots.” So how does fiction change when the revelation of secrets, especially via social media, becomes commonplace and banal? What alternative strategies does fiction employ to create intrigue and tension? It turns to a tedious dissection of the exposed self, suggests Lorentzen. Here’s an excerpt:

Outside the realm of the autobiographical, it’s to a writer’s advantage to muddy characters’ identities and conceal their inner souls. Secrets in conventional novels are the engines of plots. Asymmetrical distribution of information makes action happen. Narrative itself is the sequential disclosure of details. When the narrator is unreliable, the author is often passing secrets to the reader that the narrator registers without understanding their meaning. Vladimir Nabokov, in novels like Laughter in the Dark, Despair, Lolita, and Pale Fire, was the master of creating narrative frames around characters so enamored of their own cleverness that they are blind to the true import of the stories they’re telling, leaving readers in the position of solving riddles in works that reward rereading (and rereading and rereading) and always yield new secrets.

These games are out of fashion in an age that prizes and largely enforces transparency, not least because novelists and their characters are often engaged in a performance of elaborate self-consciousness. The end of the Cold War and the rise of omnipresent surveillance have brought new challenges for the spy novelist and the crime novelist, but transformations in feeling may have deeper effects on the novel generally. Spies and criminals always operate at the cutting edge of deception, and so novelists are burdened with treating intrigue and detection in more and more technological terms (or else, like John le Carré and any number of detective novelists, they retreat into historical fiction). But what happens in the realm of psychology when that staple of the novel, adultery, becomes a forgivable sin? Sally Rooney’s Conversations with Friends represents a revolution in the form, because it combines the novel of manners with the novel of adultery by resolving its conflicts (a breakup, marital infidelity, jealousy between friends) and dissolving its characters’ secrets in amicably negotiated polyamory. Well, that’s all to the good if you can pull it off, but something novelistic is sacrificed when characters don’t have to sacrifice anything to get what they want. Or when what they want the most is for everyone to get along.

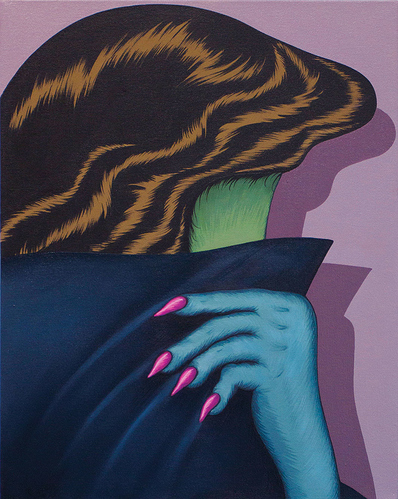

Image: Julie Curtiss, Witch, 2017. Via Bookforum.