Following the global financial crisis of 2008, a seemingly worldwide lurch towards conservatism, authoritarianism and xenophobia has seen many a journalist cast the opening of the twenty-first century as a potential repetition of the twentieth. But, while heads of state in the East and West push the world towards a situation conceivable as socio-political history repeating, there is another field in which current activity bears little resemblance to its twentieth century counterpart: the field of contemporary art.

Although the Avant-garde iconoclasms and ontological shocks of the early twentieth-century (Dada, Cubism, Futurism, etc.) were enacted by the bourgeoisie for the bourgeoisie, mostly excluded people of colour and women, and embraced reactionary thinking and proto-fascism, artists were arguably experiencing an unprecedented period of relative aesthetic and personal freedom. This liberatory moment produced work that would fundamentally break with epistemological and existential regimes of the past to ultimately set art on its course beyond Modernism to the more expansive grounds of the contemporary.

Today, despite a passion for the vocabulary of change amongst those who populate the art world’s upper echelons, and a conceptual belief in ‘rupture’, ‘paradigm shift’, and ‘the turn’, radical alteration of the field, and the concrete and cognitive institutions that comprise it – galleries, museums, art criticism, notions of best practice, etc. – has not taken place. It is true demographic gains have been made since the first few decades of the twentieth century. However, the cost of limited access for people of colour, women and the working class (extracted through a subtle process of enculturation imperceptible to some) has frequently been the relinquishment of power. It is a general rite of passage that extends beyond the historically marginalised to any artists or arts professionals who could pose a threat to the established order of things, and its prohibitory effect grows in proportion to an individual’s closeness to money, power and the establishment – a process in which the royal honours system represents the summit, or final degree of ascension.

This state of affairs has facilitated a massive transference of power from artists to institutions, from the grass roots to the establishment, and from community groups to highly professionalised and internetworked charitable organisations. The result in the UK is an art world whose only steady, top-down movement seems increasingly to be towards the absorption and neutralization of aberrant forces, and the consolidation of its own regressive institutional influence over what may be considered art or legitimate arts derived activity.

I have previously argued that the cause of this progression has been a growing identification with the 1%, seen through capitulation to the explicit or imagined whims of private finance (philanthropy, corporate sponsorship, etc.), and in turn the adoption of such practices due to institutional isomorphism – the state of inter-institutional influence in which organisations seeking entry to, or the elevation of status within, a given professional sphere mimic the formal procedures and structures of established organisations that set the bar for legitimacy within their sector. These factors play a significant role in the UK art world’s current condition, but they are part of a larger system of thought, practice and procedure – adopted by mid to top-tier museums and galleries, professionalised charitable organisations, philanthropic foundations, media outlets, private limited companies and those wishing to operate within them – that is best explained as the new conservatism.

Although an obvious symptom of neoliberalism, the new conservatism is not a formally acknowledged school of thought. The umbrella term is employed here as a useful shorthand tool to unify and refer to a set of ideas and behaviours whose effects contribute to the following three things: the aforementioned identification with and capitulation to private finance; the reinforcement and creation of an ideologically and demographically homogeneous art world; and a sector tacitly in step with state power’s agenda of using culture as a decoration for and tactic to divert attention from the human fallout of destructive government policy. These behaviours, whether consciously or unconsciously executed, help to minimize the potential risks to institutional profit, reputation, and sustainability that radical change presents.

What makes this new conservatism different from overtly rightist or self-consciously traditionalist forms is that it advances its agenda surreptitiously by presenting itself as forward thinking, inclusive and socially conscious. This hypocrisy largely goes unchecked, because to the cursory eye most progressive, politicised, altruistic or critically engaged attitudes within the art world may seem to be adopted without contradiction. But by taking a closer look at public procedures, or applying a detailed approach to scrutinizing accounts and correspondence, it is possible to uncover evidence of professional practices that undermine progression, or benefit from the same oppressive structures and exploitative logics that many artists, arts professionals, and a large proportion of the general public are either fighting against, or oppressed by.

What is crucial if the practice, presentation and evaluation of art are to have a fighting chance at radical progression in the twenty-first century (in whatever form that might take) is a redress in the balance of power, and the restoration of a workable equilibrium that includes a grass roots of equal or greater strength than its now dominant new conservative counterpart – an entity that cannot and will not support attempts to alter its restrictive structural, interpersonal and epistemological parameters.

This moderate goal is not as daunting or impossible to enact as it may seem. Although artists and arts professionals operating in this age of rampant deregulation, privatisation, and race to the bottom tax breaks (i.e. neoliberalism), might understandably feel totally unable to effect change in the wider world, doing so within their own field is both feasible and entirely possible. This is because the system (that is the art world) is totally dependent on their participation in it to survive. By simply withdrawing their affective labour, their cultural and symbolic capital, their work from circulation within exploitative inter-institutional networks, artists and arts professionals could reclaim that power and finally torch the tired myth that moral or political compromise is always, at some level, the fundamental structural inevitability of creative practice.

In sharp contrast to conspicuous or performed individual withdrawals – self-conscious breaks that serve to strengthen an absentees position in, or prepare the way for their return to, the very system a temporary act of rebellion was staged to undermine – collective targeted refusals to work with or for new conservative organisations would mean that same work could be used to grow and bolster another sector, a truly egalitarian and diverse grass roots, ground-up, minor (or whatever other term you want to use for a non-establishment, non-high finance aligned) movement whose bottom line was progression and support, not profit and its almost unavoidable corollary, exploitation. In support of such a movement, the purpose of this text is threefold: to show how the new conservatism operates so that its activity might be rightly identified as such and avoided; to track how values and institutional behaviours it supports became hegemonic; and to highlight artists, arts professionals and organisations whose works indicate a burgeoning alternative to that hegemony.

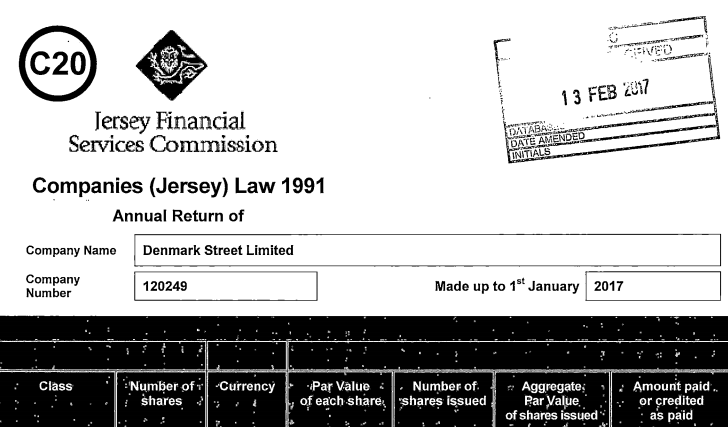

There are a number of lifestyle choices and professional procedures through which the new conservatism, when followed by individuals and institutions, capitulates to private finance, cultivates homogeneity, and works in the service of state power. But the best place to begin a survey of how it operates is with one of the most dominant and paradigmatic corporations in the field. It is an organisation whose octopoid reach spreads to criticism, curation, commissions, sales, acquisitions and much more. Its name is Denmark Street Limited (DSL).

Incorported in 2015, DSL is probably unfamiliar to most. This is because it is what is known as a parent company – an organisation set up to be the primary owner of subsidiary businesses for the purposes of (according to accountant Raj Bairoliya) ‘asset protection, tax efficiency or confidentiality purposes’. DSL is the parent company of Frieze, or more specifically it is the parent company of the two explicitly for-profit companies (Frieze Events Limited and Frieze Publications) in the organisation’s distributed, tripartite portfolio. The third business is what is known as a special purpose vehicle – a single-objective company that according to PricewaterhouseCoopers allows ‘large corporations to meet specific objectives by way of obtaining finances, transferring risk and performing specific investment opportunities’. It is named Frieze Public Programmes, and on accounts evidence has been setup to receive income from one source: Arts Council England.

Although DSL (owned by Matthew Slotover, Emily King, Amanda Sharp, and IMG Worldwide) is the parent company of Frieze Events and Frieze Publications, and undoubtedly benefits from Frieze Public Programmes (in the form of financial yields from ticket sales and increases to intangible assets like overall Frieze brand value and perceived financial viability), it is not based in the same country as any of them. DSL is based in the offshore tax haven of Jersey, a British Crown dependency described by journalist Nicholas Shaxson as an island ‘with no political parties and a government utterly captured by the financial services industry’. With its owners based in London, New York and Delaware, DSL is, then, an offshore private company that has in all likelihood been set up in an island haven hundreds of miles away for one purpose: ‘tax efficiency’, or (to quote the 1936 Duke of Westminster ruling) for the arrangement of its financial affairs ‘so that the tax attaching under the appropriate Acts is less than it otherwise would be’. In other words corporate tax avoidance, one of the major contributors to capital flight, the impoverishment of the public sector, and the widening gap between rich and poor in this country. Of course DSL may or may not be involved in the entirely legal practice corporate tax avoidance. However, to do so would be in keeping with current neoliberal company tendencies at Frieze, like its penchant for maximizing private sector profits (its own and other companies) through utilising public funds. A prime example of such activity was the organisation’s ‘page and screen’ project.

A 2015 initiative staged to explore ‘how art criticism can translate into the medium of video,’ Frieze’s ‘page and screen’ scheme used ACE support to reduce its own expenditure on the production of content. Three regular contributors were each offered the chance to direct a video and develop an essay as part of the project, which had (according to Frieze publishing’s Grants for the arts application) an overall cost of £50,440, with £15,000 supplied by ACE. Each of the writers was to be paid £1,000 in total, £500 for a video and £500 for an accompanying essay. Other costs were listed as £12,528 for marketing, £424 for editing (texts), £5,458 for project management, and £2,025 for a public event; while the sum of £27,005 (approximately £9,000 per film) went to production company Pundersons Gardens for costs including ‘equipment, travel and specialist personal [sic]’. What this inventory of outgoings illustrates is Frieze’s use of public money to fund a project where approximately 94% of expenditure went toward increasing the tangible or intangible profits of private companies (that of it’s own and Pundersons Gardens).

This use of public money to boost private profits is at issue here, given Frieze publishing lists its income for 2014 (or the last financial year) in the GFTA application at £2,132,674, an astronomical sum that must include income from Frieze Events. Taken alone the profit and loss accounts of Frieze publishing stand in sharp contrast to those of its closest sector rival Art Review. Both publications produce fairly similar in-house content and are ultimately based in offshore havens (Art Review is a subsidiary of parent company Art View Limited, registered in Gibraltar), but the crucial difference is in the finance.

In 2015 Frieze publishing registered a profit of £511,714 (all figures according to accounts submitted to Companies House), while Art Review registered a loss of £167,875. For the sake of comparison Aesthetica Magazine registered a profit of £1,493, Art Monthly a loss of £93,754. It should be said that the complete details of profit and loss totals for small companies (i.e. those that do not earn more than £10 million per year) aren’t published and so the full story behind the numbers, the apparent losses (which may not be losses) and gains (which may not be gains) can, to an extent, lay beyond the figures. However, on the face of the numbers set out in the above publications’ respective 2015 accounts, Frieze is the most anomalously profitable magazine in the UK. The point is that it had no discernible need of financial assistance. Especially when that assistance amounted to three percent of its half a million profits in that year. What, then, compelled the organisation to ask? What compelled ACE to fund?

In place of the principle that in addition to artistic and cultural merit, access to public funds should be dependant, to a large extent, on clear and demonstrable need, both the request and subsequent funding of ‘page and screen’ seem to have operated in line with the commercial logic of the mutually beneficial partnership. Frieze produced content at what could have been zero cost, and by securing public funding again demonstrated their distinction from other commercial initiatives (fairs, magazines, galleries) unable to do so. ACE continued one of its model public-private partnerships with a commercial institution that perhaps perfectly demonstrates the ideal commitment to producing both profit and significant cultural contributions to the UK’s soft-power portfolio.

Mutually beneficial partnerships are part of a wider strategic culture that strengthens and reinforces the spread of new conservatism, and subsequently impedes progressive development. If we define strategic culture in the art world as a set of institutional procedures and behaviours that facilitate the progression of favoured and low-risk individuals, practices and ideas, then we can also identify homogeneity as an inevitable outcome. In her recent book ‘When Attitudes Become the Norm’ Slovene art historian and theorist Beti Zerovc argues that in the 1990s ‘the practice of curation underwent an intense process of professionalisation’. This occurred precisely at the moment that the art world increasingly required ambiguous figures who specialized in building bridges between critically engaged art (including the toothless practice of institutional critique) and private finance, individuals she describes as capable of ‘acting not only as an agent of change but, even more, as an agent of neutralisation’.

Performing this function is now pervasive. Consider the corporate backed Art Night 2017 (supported by auction houses Phillips and Dorotheum, and private Swiss bank Lombard Odier) with its cod-liberatory entreaty, voiced by curator Fatos Ustek, for attendees to ‘join us on the streets [to] celebrate the differences that make us’ despite fielding a programme that included no British Asian, black, or discernably white working class artists; or new ICA director Stefan Kalmar’s desire to create an ‘organization that takes risks [and] challenges the status quo’, whilst hosting events like its exclusive annual ‘friends of’ dinner, sponsored by fashion house Lanvin, in honour of alleged Tory supporter Bryan Ferry, with music supplied by Isaac one of Bryan’s four Eton educated sons. At the institutional level, consider how the anti-racist sentiment in curators Mark Godfrey and Zoe Whiteley’s much trumpeted celebration of art in the age of Black Power ‘Soul of a Nation’ is profoundly undermined by the funds Tate received from Leonard Blavatnik towards the eponymous gallery extension opened in 2016. The Ukranian billionaire also gave $1 million to Donald Trump’s inaugural committee, a president favoured by the Ku Klux Klan, Neo-Nazis, and White Nationalists, who many feel has done much to legitimize and embolden the far right, and is expected to do considerable harm to race relations in America during his term.

The new conservatism pitches these behaviours and linkages as the necessary and negligible price to pay for art. As a result the bridging myth endures as a fixture of best practice and institutional common sense. It operates as an ideological filter that contributes to and ensures sector homogeneity: those who are happy to embrace its logic progress; those who are not seldom do. 1992 is an important year in this regard. In politics, Tory MP Norman Lamont introduced the Private Finance Initiative; the flagship public private partnership (PPP) policy enabling contracted private firms to manage public infrastructure projects (hospitals, schools, rail contracts, etc.), a venture significantly increased during New Labour’s ’97-2010 tenure. In the art world Frieze began publishing, and the Royal College of Art’s Curating Contemporary Art MA was launched under the directorship of Teresa Gleadowe. Politicians set the PPP climate that would spread to and inform an increasingly private positive UK art world, and institutions like Frieze and Gleadowe’s CCA produced arts professionals, curators and directors trained to navigate and accept its logic, however grudgingly, but not to question or dismantle it – a sample of current directors who went through this trajectory includes Sam Thorne at Nottingham Contemporary, Sarah McCrory at Goldsmiths Gallery, Polly Staple at Chisenhale, Sally Tallant at Liverpool Biennial, Francesco Manacorda at Tate Liverpool, and Helen Legg at Spike Island.

While there is not enough space here to map all the internecine links between arts organisations in the UK (a network forged through personal and professional relationships, inter-organisation board memberships, and cross-institutional career progression), the trend is growing. For example Plus Tate, an initiative launched in 2010, links UK-wide institutions to Tate gallery in order to produce ‘a powerful group enabling new collaboration and change’. The roster of Plus Tate galleries (including five of the six listed in the previous paragraph) has now swelled to a near sector wide thirty-four (of which none are headed by British Black, South or East Asian directors).

Although collaboration and data sharing undoubtedly take place, the by-product of the initiative has also been the creation of a large inter-institutional, closed network. Typically the benefits of such phenomena are that members find movement easier within a unit whose identity is based on standardized professional practices, shared norms, and values they themselves establish. Detrimental effects include the reduced potential for dissenting voices within the group, further professional and reputational marginalization of those who are outside it, and a concentration of power at the centre. To be clear, the intention here is not to paint strategic culture as intrinsically sinister, nor is it to accuse the thirty-four directors, former Frieze staff, or RCA alumni of underhand tactics. The intention is to identify facets of the new conservatism and to illustrate how these states of affairs strengthen and reproduce a pre-existing model.

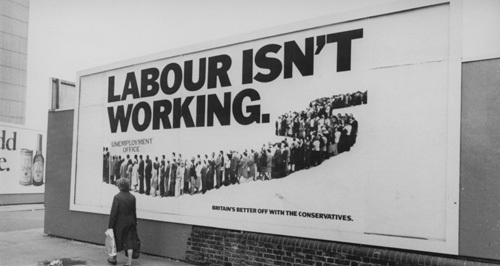

The above examples show how the new conservatism is operating today, but what are its roots? How did it come to prominence? 1990 was the transitional decade, but the ‘80s and Thatcherism – that is the policies pursued by the Conservative government under Margaret Thatcher, and the cultural and ideological shifts in public opinions, attitudes and beliefs they caused – prepared the ground. Specifically, Thatcher presided over the destruction of labour unions, the deracination of the working class in particular and communities in general, reducing the public sector and, in the words of Conservative MP Oliver Letwin, ‘privatising the world’. Many community focused arts and culture initiatives were gradually defunded and ultimately, by the ‘90’s onset, dissolved.

In the UK’s capital the Greater London Council (GLC), and the Inner London Education Authority (ILEA) were wound up in 1986 and 1990 respectively. Both organisations were beacons of progressive, anti-racist, left leaning activities whilst under Labour control in the 1980s, and helped to support and build projects that included, but were not limited to, community workshops, free arts and music festivals, educational broadcasting, school library provisions, and free musical instrument training and cultural activities for children. Such organisations were the official backdrop to smaller grass-roots initiatives like the Keskidee Arts Centre, the UK’s first arts centre for the black community, which closed its Kings Cross premises in 1991, and Centreprise, a bookshop and community cultural centre in Hackney that hung on until 2012.

27 October 1986 was a key date in Thatcher’s agenda to, in the words of poet Linton Kwesi Johnson, ‘gradually strengthen the hand of capital and weaken the hand of labour’. According to journalist Iain Martin, this was the year that ‘a switch was flipped and the Stock Exchange was opened up, liberalized and computerized,’ a dramatic alteration known as the ‘Big Bang’. The effects of the deregulation, liberalisation, and internationalisation of city finance, consolidated London’s status as the global financial capital of the world, birthed Canary Wharf as a business district, fired the starter pistol on rapid gentrification, and redoubled the City’s status as, what journalist Anthony Sampson once described as, ‘an offshore island in the heart of the nation.’

As international money flowed in, public money was cut off and privatization accelerated. The socio-economic ripples from this explosion of financial liberalisation helped to push the arts and culture sector towards a more corporate, bureaucratic professionalism, funds previously available to informal or ad-hoc grass-roots organisations became increasingly difficult to access and drifted up into the hands of museums, galleries, private companies and non-profits. These organisations gradually expropriatated the language of engagement, strategies of outreach, and educational initiatives and essentially took over the community arts sector’s participatory territory.

Over two decades of this process has yielded large PPP organisations like the commissioning agency Create (of which Frieze’s Slotover is a trustee), and Open School East (OSE) founded by former Frieze employees Thorne, Laurence Taylor, McCrory, and their colleague Anna Colin. Whereas organisations like the Keskidee were run by marginalised community members and sought to train, empower, support and hand over the reigns to that same citizenry, Create and OSE do things differently. Theirs is a kind of ostensible social enterprise that uses the same citizenry to do two things: to secure and elicit public and private funding for projects that use East London’s low income populace as either their medium, material or target (see Create’s Chicken Town, a 2016 project with Assemble that produced ‘a not-for-profit restaurant offering a delicious alternative to the growing number of chicken shops on the high street that sell cheap, poor quality and unhealthy food’); or to fund their own operations (according to their 2016 accounts Colin, Taylor and possibly other OSE staff paid themselves £57,392, spent £90,308 on its associates teaching programme, £18,819 on community projects, and £12,394 on projects – delivered by unpaid associate artists). For those watching the acceleration of social cleansing in London and thinking where next, Woolwich may well be it.

With property prices and land value in general set to drastically increase as a result of Crossrail links, the expected influx of high earners is fueling the ‘new masterplan’ for the Royal Arsenal site which will include ‘3,750 new homes, and new cultural, heritage and leisure quarters.’ In North Woolwich the London Borough of Newham (whose Mayor Robin Wales’s abysmal record of public-sector defunding and family displacement has been documented and fought against by the Focus E15 campaign group) are supporting Create’s management of the Grade II listed Old North Woolwich Station, to be inhabited by OSE, ‘creative businesses and artists’. The development of rail infrastructure, the hiking of house prices, the sudden appearance of professionalised arts and cultural organisations to replace or manage the work of informal community organisations, the commercial branding of neighbourhoods using that same professionalised arts and culture as a cover: this is, of course, the same model of gentrification we’ve seen applied elsewhere (Peckham, Hackney, etc.), and all the preparations are being made for massive community displacement.

Taking all of the above into account the new conservatism’s sector dominance augurs a bleak future. However there are artists and organisations whose work indicates positive directions for potential change.

One of the most important factors in the development of arts and culture this century will be access to financial capital. Its scarcity following the global financial crisis and public cuts has seen institutions turning to private finance (in all its forms), and the professional standing of those with easy access rise significantly. In opposition to this retrograde step artist Ellie Harrison, community activist Jain McIntyre, and Curator Cecilia Wee, are developing the Radical Renewable Art and Activism Fund (RRAAF). Aiming to use ‘renewable energy as an alternative funding source for socially and politically engaged art-activist projects’, RRAAF’s co-operative model (shared ownership of a company whose profits from the sale of ethically sourced energy would be used for grants), could be scaled up and reproduced elsewhere in the UK. Their scoping document is available through www.rraafund.org and offers a serious alternative to the pervasive acceptance of economic exploitation that sees even bequest-based grant givers like the Elephant Trust relying on profit yields from an investment portfolio that includes Shell Oil.

On the gallery side, Turf Projects is the first artist-run space in Croydon and crucially it was founded by a young team who are personally committed to the area, dedicated to supporting its community, and are conscious of the need to resist the instrumentalisation and commercialisation of their activities. With well-curated exhibitions, studio provisions, open crits, and their collaborative initiative with the Makers of Stuff Squad (a collective of artists with learning difficulties or mental health issues), Turf are indicative of a wave of socio-politically engaged, and ethically minded young artists entering the field with a civic focus and level of ethical professionalism older artist-led organisations are still struggling to come to terms with – while the PPP operating Cubitt Artists’ (supported by Outset and Deutsche Bank) set up its education programme in the 1990s to keep ACE funding it was under threat of loosing, Turf’s education and community engagement are intrinsic founding principles.

In criticism Gabrielle de la Puente and Zarina Muhammad’s website ‘The White Pube’ presents one of the first truly new voices in British art criticism in the twenty–first century, and most importantly its writers have risen to prominence without the help or patronage of Art Review, Art Monthly, Frieze, or any of the other publication or established platforms in the UK. Informal yet stylistically innovative, art historically rigorous without the staid academicism or florid pomposity of much established writing, the pair’s mix of reviews, essays, podcasts, and social media posts are bound together with a singular critical voice grappling with contemporary issues of race, gender, sexuality, aesthetics and ethics. Rather than the brattish, sneering insider defamations of anonymous online blogs of the past like Cathedral of Shit, The White Pube’s irreverent criticism comes from a personal perspective that is publicly attributable to both authors. This is all the more significant given their focus on artists of colour, in a field that is still comprehensively monocultural. A rough, approximate sample (i.e. detailed in-house demographics may tell a different story) taken from the top three UK art magazine’s summer issues showed Frieze had a quota of zero discernably British Black or British Asian writers in fifty three separate contributors, Art Review a possible two (Nirmala Devi and Sarah Jilani) in thirty seven, and Art Monthly zero in twenty three - surprisingly, from August 2016 to August 2017 out of 103 separate contributors, Art Monthly had two discernibly Black British writers, and possibly two discernibly British Asian writers.

Creating avenues for funding separate from exploitative networks, organizing gallery spaces with a sense of civic responsibility, and devising opportunities for new critical voices invisible in a staid sector, aren’t they all the basic ingredients for a self-sustaining field? What would happen if these and other actors on the periphery engaged in similar activities came together? Could a unified drive towards extrication emerge? Would a robust and potentially radical art world then be possible to build from the ground up? Would an art world liberated from tired orthodoxies be possible? These are all pertinent questions, because although the new conservatism is a terminological invention, the behaviours it has been used to refer to above – the performance of progressive tendencies alongside actual capitulation to private finance, the preservation of an homogeneous field, and activities in step with the state’s agenda to instrumentalise arts and culture – are very real and metastasizing.

In the face of such developments the question of institutional or sectoral reform now seems mute. For at least forty years reform has been the rallying cry driving articles, books, exhibitions, institutional critique, protest, endless symposia, and what have they yielded? Little change, but plenty of critical awareness. The type of awareness that encourages gallery directors to avoid political conversations with patrons who favour free market economics and the Conservative party; the type of awareness that allows editors to commission articles on the need for diversity, when their own magazines are more monocultural than the local police station; and the type of awareness that has produced artists whose words and works explicitly decry racism, capitalism, sexism, gender normativity and so on, but remain silent and mysteriously conflicted when it comes to the actual money, institutions, and individuals who support both their works and the systems of repression they critique.

This willful inattention is what preserves the current state of affairs, but it needn’t be so. Despite protestations that the pervasive and inescapable reach of neoliberal capitalism has created an existential framework in which compromise and complicity are the new original sins, I suspect silence, resignation or apathy are fuelled by something far more basic, comfort. Put simply, people are adverse to personal risk and lifestyle change.

If radical progression and a separation of art from systems adversely effecting people across London and the rest of the United Kingdom, is to stand a chance, then it has to start with a reclamation of agency from actors who have been conditioned to believe they do not have any. Replace, or at the very least augment, the impulse to engage and reform with a robust effort to withdraw and rebuild.