In the March issue of e-flux journal, Jane DeBevoise writes about artists in the post-Mao, economically liberalizing China of the 1970s, '80s, and '90s. In contrast to Western artists, these artists tended to view the private art market, which was just emerging in China, as a force of creative liberation, since it freed them from the narrow aesthetic confines of state-supported art venues. Here’s an excerpt:

But starting in the late 1970s, China embarked on a series of far-reaching economic reforms. Beginning in the agricultural sector, these reforms were aimed at re-igniting a stalled economy and were defined by the appearance of a market, first in the countryside and soon after in towns and cities, where farmers and villagers alike sold produce and handmade products for prices determined by supply and demand, rather than state policy. By the mid-1980s these economic directives had expanded to include some of the large state-owned enterprises, from media concerns to manufacturers, who were encouraged to become financially accountable and to make a profit.

The state agencies in charge of cultural programs followed suit, organizing exhibitions at first of ink painting and later oil painting that were sent abroad, to Japan and the West, to develop diplomatic ties and to generate business opportunities. In an effort to accumulate foreign currency, shops selling paintings to an increasing influx of tourists proliferated all over China. Even the National Gallery expanded its retail initiatives, rented gallery space, and hosted sales exhibitions, like the series organized between 1986 and 1989 by the Beijing International Art Palace, a partnership between the Chinese government and a Japanese real estate developer. Headed by Liu Xun, a senior official of the Chinese Artists Association, the Art Palace held fifteen sales exhibitions at the National Gallery, until establishing its own gallery at the Holiday Inn Crown Plaza in Wangfujing in 1991. The pressure to generate income became so great that the National Gallery started rotating their exhibitions with almost unprecedented frequency. By 1988, it was presenting two-hundred shows a year, of which 95 percent lasted less than two weeks and many were only open for a few days. The museum had begun to resemble a commercial gallery, and the largest percentage of work displayed in these short-term shows was ink painting. Ink painting was the most commercially viable form of art at the time, and, despite the hype around the handful of oil paintings that achieve six or seven figure prices, ink painting still accounts for the largest segment of the domestic Chinese art market today…

But it wasn’t just fee-hungry museum administrators and organizers with overtly commercial goals who saw the possibilities inherent in the newly emerging space between the state and the market. Champions of experimentalism saw it, too. In 1985, after three years of effort, Robert Rauschenberg succeeded in procuring gallery space at the National Gallery from the Chinese International Exhibition Agency, an arm of the Ministry of Culture, to produce an installment of the Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange. Gao Minglu, the indefatigable advocate of the Chinese avant-garde, was one of the purported 300,000 people who came to see Rauschenberg’s show. He would go on to rent the National Gallery himself after raising funds from several sponsors, including a fast food entrepreneur named Song Wei, in order to present the now infamous “China/Avant-Garde Exhibition” in 1989. And it was here that the market imaginary for Chinese contemporary artists finally stepped out onto center stage.

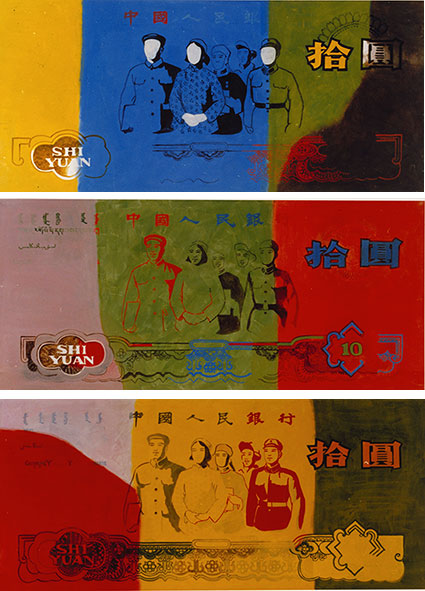

Image: Yu Youhan, Renminbi, 1988. Oil on canvas. Photo: Carl Brunn. Courtesy of the artist and Ludwig Forum Aachen, collection Ludwig.