I try to reply a little to Greg’s last “ethos of radical scholarship” question, and then play catch-up below on the other two questions.

The “liberation of a a general creativity” is indeed a noble aim. Helping the people to find their voice, and, in the face of a jobless future, to find their vocation is something artists can do. But this kind of mission is not the same as seeking a hermeneutics, a philosophy of communication, for “different species of artistic object/action/thing/practice.” (In fact, this isn’t new; I recall Martha Wilson’s turn of the century development group for an archival system adapted for experimental intermedia, performance and hybrid forms, which is a kindred problem.)

Dan Wang expresses skepticism, rooted again it seems in the alienation of social movements and political infrastructure from academia. Sure, “social practice attracted capital,” but my guess is its hold on university resources is tenuous and slippery. It’s an old west false front on what is really a tiny town. Stephen Duncombe’s emphasis on “socialization and mobilization,” the production of “self-help” books like “Beautiful Trouble” is part of the answer. But there needs also to be a network of popular universities, workers free schools, what the Spanish call “ateneos” to present and discuss these playbooks.

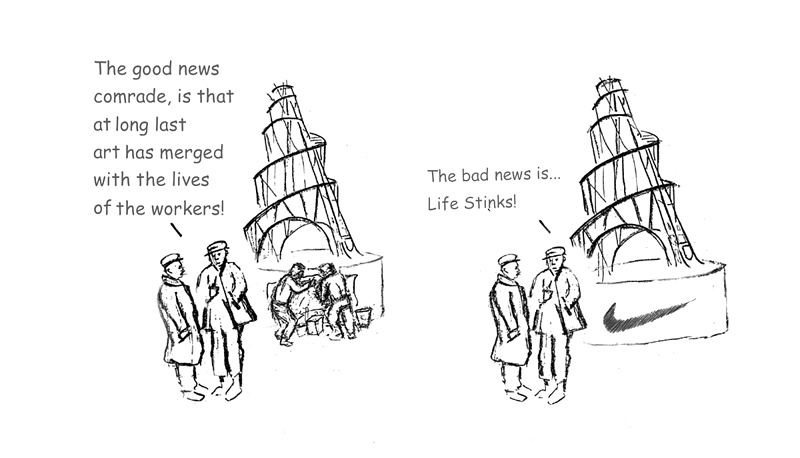

What we are confronted with now is not the “liberation” of general creativity, but its systematic and overarching commoditization, its mobilization as the new field of popular culture, its instrumentalization, and “farming” – the relentless extraction of an attention tax on every moment of its exchange. This is profoundly confusing.

Blake Stimson seems to suggest resolving the “bourgeois contradiction” by (sigh) simply remaining bourgeois. He reads the “tent cities and ad-hoc libraries” of OWS as only seeming like “harbingers of a new and better world.” Somehow, this global appearance of instant social centers (i.e., pop-ups of venerable forms of modernist left organizing) meant “we had already lost the fight.” Heaven forfend that in “reaching for need” (vital, indeed) we should sink into the “fetid feudal dark matter of the art world and below.” Gee, no liberation there! Only the stuffy, smelly, tedious solidarity of slaves. All righty, then. Very many of us are there already.

Joanna Warsza writes of what Yates calls the “moment of breakage” between art institutions and “the new space opened by Occupy.” She says these moments don’t last long, which is true. But this 2011 was a crest, a coming into public view of stuff that was going on for a long long time. This cresting left art and subculture behind, and became functionally political (15M into Podemos and related formations).

Derszer’s suggestion, based on the “Making Use: Life in Postartistic Times” exhibition in Warsaw, that museums can be information points to “report on practices” which are “an-art, post-art” etc., is very European. EU art institutions are largely publicly supported. U.S. institutions, which are funded by the 1% mostly in finance and real estate, are not about to serve as infoshops for post-capitalist development.

Finally, my own “radical scholarship,” since I am involuntarily retired from academia, revolves more around questions of militant research. My “House Magic” zine project has been dedicated to propagandizing the political squatting movement, and recovering the extraordinary histories of the movement’s projects. These are not just forgotten; they’ve been suppressed. Our group, Squatting Europe Research Kollective (SqEK), is committed to returning academic knowledge to the movement. How exactly that practical ethic of research and publication translates into the world of art, both market and institutional, is rather up for grabs.

And then, while I was traveling I had a chance to reflect some on the earlier questions, #2 in particular, which I can only post now:

Yates’ description of Zucotti Park quoted by Greg could be compared with the occupation of Gezi Park in Istanbul, which happened in part during an international art exhibition, and in which numerous artists took part. This is an important conjunction – a moment – which needs more scrutiny, despite that it is now drowned in a torrent of government reaction. Yes, “moment” as Nato observes, in evolving a criticism germane to the art and activism conjunction, we must respect its fluidity, its mixing, and talk less about genres or technical practices than about these moments.

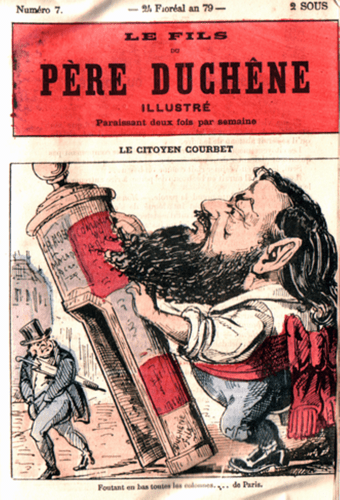

In this centennial year (2016), Claire Bishop observes that Dada was connected to anarchism, but loosely (um, directly in Hugo Ball’s researches), and was “rejective” of art tradition – I think not, but rejective of contemporary art practice, yes! Now, as mjleger put it, “Strike Art uses a Derridean deconstructive register to place the word Art ‘under erasure.’” It’s all there, but artists are undercover, artists without portfolio. All the old traces of rebellion are there in tradition, even unto the Cathars. Not the Dadas, but the Surrealists mobilized them all more coherently (for 2021!). Among allusions to classic “artpol actions” as Dan Wang mentioned, we must include the activist clubs Rodchenko modelled in 1925 and Dmitry Vilensky explains in his texts directly in relation to social centers. Chto Delat has recently reconstructed these in museums in a kind of hot rod artpol antiquarianism

Claire’s reference to “Hirschhornesque hand-made signs” of OWS, as others have observed, reverses the flow of influence, from artist to social movement. I am happy that Hirschhorn’s unacknowledged appropriation of the social center movement tradition and form has at last been recognized, even if only in these replies. But that phrase betokens also the moment of recognition, when the function of a fetish is understood. It’s an evolution; Hirschhorn hires his collective.

Looking for coherence in the field of creative production in the thick of a social movement is going to be unrewarding. Artists can make that coherence, but only as a simulation, and only retroactively, as camp followers. In the thick of struggles, it makes more sense to me to search rather for the texture of engagement, the gyrations in the ethos that are underway. It’s a question of working on a kind of listening rather than precepting and propounding.

For the larger social issues, the futurology we work under the banners of utopia – Stevphen Shukaitis is succinct: “OWS represented the visible manifestation of a shift in class composition more broadly.” Just as Dadas and Constructivists exalted the engineer as the Fordist era with all its dislocations kicked in, artists now might exult the employment counselor for the jobless future as the age of robots and artificial intelligence swamps the world’s working stiffs.

As for the Occupy movements as moments of supersession, I am so happy I was there! Happy too that it all seemed so familiar, those camps, from the many social centers I had visited. It was simply normal! As to what was occurring, it was the return of the historically repressed, the ‘parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme’ of the commons, the fair. Again as mjleger said: “the operative term here is the commons, a concept that acts as an ontological placeholder,” yes a way of being, and an ethos, even an imperative, for acting.

It is a term in legal philosophy, historically explicated by Peter Linebaugh, and developed in Italy as a constitutional proposal by Ugo Mattei. Many today, like the young Lucy Finchett-Maddock are working to make this more real. Artist Adelita Husni-Bey’s project on devising a “convention,” or proposed law on squatting for governments to adapt, using an assembly-based process of composition, as an art project – is an important prefigure, and even more, a real job of work. And there is even an art product! (Made with Casco Projects, Utrecht, as an outgrowth of their long-running Grand Domestic Revolution investigations.)

Vilensky’s texts continually ask the artist: “What is the use of what you do?” While I sympathize that to confront such a question might drive some to suicide – we all need something to do, even if it’s not “useful” – it’s a good, if Soviet-hard rule of thumb for artpol. So, are we serving the movements? If so, we must understand them.

Dan Wang writes, “By the fall of 2011, all the insurgencies were visible to one another.” (Yes, but they remained invisible to the public of the Spectacle, and the U.S. TV pundits were baffled, turning for the first and last time to the likes of David Harvey and David Graeber to explain it to them.) The work of understanding them, involving much cross-comparison, is quite important. I am thinking of what I know but don’t understand – the Agora 99 in Europe before Occupy, or even in the Spanish context, 15M; and of the student movement organizers’ visit to Tunis even before the Arab Spring. There is a track of major organizing going on which is the job of social movement analysis to uncover and make clear. I doubt that this could really be part of art history. When I was teaching survey art history, I had only the vaguest of notions what the Holy Roman Empire was, much less the political conditions in most of the countries and epochs I was teaching.

What can be done, especially in teaching, is to undertake a real analysis of collective practice. This can be put together with recent political analyses, like those of “constituent power” and culture, like Luis Moreno-Caballud’s recent “Cultures of Anyone.” This should be an emerging concern of art theory, even though it is in a sense management theory. (That’s why already there are anarchists in business schools.)

If artists working collectively, working in service of movements, understand themselves and the way they work, then they will not be so easily subsumed by the demands of the Political, nor exploited by the libtards* of Silicon Alley (*that’s “libertarian bastards”). Dan notes that suppressive effect in OWS: the “libidinal energy of an avant garde worth the name seemed absent, replaced by the General Assembly, a collective performance of radical civility and radically respectful multi-logue.” A strong critique of the GA came out of the Occupy Artists Space action, which Andrea Liu has continued to work on. So, no, you don’t have to go to all those meetings – but you do have to go to your own.

So far as Dan’s reading of “the history of New York Occupy as a formative moment for the emergence of yet another art world” goes – I don’t see that on the ground around the USA, as it were. There are people, and online projects, and scattered pockets in academia. But the kind of networks that existed in the '70s and into the '80s for politicized cultural work I do not see. I have recently seen the melting away of the post-Global Justice movement infrastructure, infoshops and the like, and its replacement by a demographically bounded music culture scene (white punks on dope), and pockets of anarchists.

The academic art world is a place where some politics can live, yes, but under heavy constraint. Academia does not build any networks but its own, and the centripetal force is tremendous. The big job is always to get outside the walls – but, as everyone knows, you might get stuck out there when the drawbridge goes up.

Thanks to Gregory and every poster for this very stimulating discussion.

@chloebass I led a panel at the art Amway convention otherwise known as CAA called “Critiquing Criticality.” That panel specifically addressed many of the points you raise (it will be a book due to be published next year). I have been saying for a decade or so that “art for art’s sake” has been supplanted by “criticality for criticality’s sake” and we are no better off - now essentially trapped in an anti-emotional Napoleon complex called graduate art education. That leads to @gsholette’s questions regarding expert culture and its instituitons…because I am feeling lazy and because I have dealt with this subject matter in detail way too many times, I will let Kurt Spellmeyer answer:[quote=“e_flux, post:1, topic:3560”]

Where has the spirit gone…

[/quote]

Although “the spirit” Greg is asking about is an avant garde intellectual poltergeist and it is scaring us from leaving art’s haunted house once and for all…

Spellmeyer [empahses mine]:

The rarification of the arts – their sequestration from everyday life and their metamorphosis into objects of abstruse expert consumption – typifies the very essence of disenchanted modernity as Weber described it, and this development corresponds quite closely to other forms of political and social disenfranchisement. But the academy’s appropriation of the arts may have social consequences more important in the long run than even the plummeting rate of voter participation or the widespread dissatisfaction with, say, the public school system. Fundamentally, the lesson of all the arts is the same: ways of seeing, ways of thinking, ways of feeling can be changed, and each of us can change them. The arts, we might say, dramatize the human power of “world making,” to take a phrase from Nelson Goodman, and they do so by freeing the artist from the ordinary constraints of practical feasibility, empirical proof, and ethical uprightness. Once the arts have become nothing more, however, than an object of specialist inquiry, they often cease to teach this crucial lesson and teach instead exactly the opposite: ways of seeing, thinking, and feeling might be changed, but only by exceptional people.

…

Once again an insight from the “New Age” may be more truthful than we wish to admit – the insight that the arts share common ground with the kind of experience we think of as religious. It seems to me, in other words, that unless English studies can offer people something like an experience of “unconditional freedom,” we have nothing to offer at all. If a poem or painting is always only a product of social forces, an economy of signs, or some unconscious mechanism, then why not simply study sociology or economics? If all we have to show for our reading and writing lives is a chronicle of ensnarements, enslavements, and defeats, then why should anybody tramp so far afield – through, say, the 600 pages of Moby Dick – when we can learn the same lessons much more easily from People magazine or the movies? In itself, the forms of activity we speak of as “the arts” can be put to countless uses for countless reasons, but we might do well to ask if ideology critique is the best of those uses. Does it seem credible that the millions of years of evolution which have brought forth humankind’s marvelous intelligence have now come to their full flower in our disenchanted age? Was it all for this? Or could it be, instead, that disenchantment, the failure of all our narratives, is now impelling us toward the one encounter we have tried for several centuries to avoid, having failed, perhaps, to get it right the first time around: I mean an encounter with the sacred.

I’d like to add my thanks to Greg for the opportunity to contribute to this fascinating discussion, and to Yates McKee for the book which has prompted these responses.

One of the things that interest me about Greg’s question is its emphasis upon is the relationship between the work (the ‘object / thing / action / practice’) and its analysis or description through criticism. The works that operate in the space which Greg calls ‘bare art’ – a brilliantly succinct way of capturing the conundrum of the art /non-art oscillation of OWS – have a deeply problematic relationship to criticism. If there is a project of ‘exit’, it is criticism that often returns this project to an expanded and newly stabilised concept of art. As Greg has suggested, the project of ‘exit’ dates at least to the 1960s (but emerged then by way of rediscoveries and reinventions of avant-garde exits of the 1920s). I think we might say that there are two forces at work within this history. First, the challenges to the integrity of art by radical artists who try to move beyond the apparently timeless space of the museum. But, in a strange mirroring movement the pressure of capitalism itself has undermined art’s autonomy, pressuring art and recreating it in its own image. In my view this is a sign of capitalism’s weakness rather than its strength ( as suggested in a previous post). Capitalism has pillaged one of its most important forms of legitimation. Art once existed somewhere between Elysium and safety valve, where it was possible to imagine a futurity in which the contradictions of capitalism might be reconciled. Now, contemporary art operates without a significant sense of futurity. But, without it, some of the revolutionary energies that were coralled in art’s enchanted space have reemerged in the strange, impure, ‘bare art’ or prefigurative politics of the global Occupy movement and other such developments. John Roberts calls them ‘revolutionary futures past’ and this seems to capture something of it.

Theory, including art theory which preserves and circulates radical thought of the last century, is woven into the politics of these movements. So, I entirely disagree with the contributions above that want less ‘self-criticism’ and more ‘action’. Self-criticism brings forth effective action, it is not opposed to it. But, at the same time, to frame OWS as an ‘artwork’ seems to risk securing its identity, removing the impurity and ambivalence that was so striking and inspiring in 2011. How does criticism avoid stabilizing ‘bare art’ as ‘mere art’? For me, this is perhaps one of the most important critical challenges of the present. The position that makes most sense to me is to write in such a way that the institutional function of art criticism is decomposed from the inside by the aporetic power of bare art, by its ambivalence, its refusal to be located. Bare art can be written about as an artwork only in so far as it is allowed to corrode conventions through which art is addressed. Ideally, the marks of corrosion should be left on display – to act as testimony to the crisis and to encourage whatever it is that bare art attempts to bring into being.

What you have brought up Greg resonates with me as a percarious artist and arts instructor who instructs others on what it means to make art in a business/capitalist/neoliberal driven artistic economy. My involvement as an artist has primarily been art that expands into the political, or art that expands on notions of collective agency. The dominant main stream contemporary art world is not interested my existence, and I am only half heartedly interested in it’s constructed self image, since this is the dominant commons I am forced to work through in order to survive emotionally and economically. I am more interested in engaging in the artistic “undercommons,” than the art system commons, but not sure sometimes how to survive and negoiate how this complicity eats away daily at my being. All I can do is keep creating relationships/alliances to keep my percaious artistic hybridity moving forward.

And this movement forward I think has to be not anarchocommunism as modeled by OWS, but the reverse: communoanarchism. We need to think of the bigger surroundings of political change (universal everything: healthcare, employment by shorter work days, housing, etc), how this political prefiguration of the undercommunism, allies with the artistic undercommons.

This has always been my notion as an artist, maybe because I am an immigrant from the West Indies, who always feels displaced, colonized and in search of a decolonized existence, in every sense of the word.

My thoughts about this question reinforce my responses to the first two. There is much to gain from the discourses and practices identified under “contemporary art,” where contemporary art is not only a chronological designation but also a self-conscious mode, one that understands and often ironizes its embeddedness within art institutions, etc. Such practices also engage with “contemporary” social and biopolitical theory, thematizing it in these artworks, citing it in curatorial statements, and invoking it on e-flux discussions like this one. I find myself inspired and challenged by such art-making and such discussions.

But Greg’s question is also a reminder that this network of activity around contemporary art is a social formation, an “expert culture” that has its own habits and blindspots. As I noted earlier, differently positioned artists and organizers might see very little need to give “contemporary art” such analytic importance in the elaboration of a socially progressive politics, even and especially those whose primary pursuit is an equitable and ‘general’ creativity. Some artists and organizers have not felt compelled to enter a contemporary art world, and hence felt no compulsion to stage an ‘exit,’ especially when the declarations and documentations of that ‘exit’ are so easily bought and sold. From another angle, some artist-organizers might also become impatient with a mode of institutional critique that is so busy ‘exiting,’ that it does not, as Caroline W suggests, “build and support institutions that are as radical as the artworks we create.” That kind of commitment might require skills other than those traditionally taught in art school. It might require a different reading list. Having just finished up a pre-Open Engagement conference on cross-sector collaboration today (http://arts.berkeley.edu/cross-sector-conference/), I also think it might mean finding compatriots in sectors your avant-garde training taught you to resist, to disdain, or to disrupt. When I started exploring the idea of an “infrastructural aesthetics” for Social Works several years ago, this is the kind of institutional reimagining I had in mind. It is a value that I hear in Dan Wang’s articulation of OWS and in his relief that a “another avant-garde legacy failed to return” that is, the idiom of “transgressive aesthetic disruption.” Instead, of “trashing the plaza,” Wang recalls how “folks in Zuccotti managed trash removal, and then put together a library.” The distinction between institutional disruption and infrastructural repair is one whose politics we endure daily in the Silicon Valley, where the older avant-garde idiom is easily appropriated to celebrate the neoliberal and libertarian effects of “disruptive” technologies.

The distinction also recalls one that played out during the UC budget crisis when students and faculty began to realize that the anti-Machine discourse of the Free Speech Movement was not fully adequate to the task of saving the system—the Machine?—of public higher education in 2009-2010. I was glad to see Yates McKee placing UC activism on a pre-OWS genealogy. When students “camped” in Wheeler Hall in 2009, they were in fact re-figuring a prior pre-figuring. FSM students had camped in Sproul Hall nearly 50 years earlier. But the location and the symbolic effects were, to my mind, quite different. In 1964-1965, students camped in an administrative building; in 2009, they camped in the English department, the seat of liberal arts education. Whereas one era targeted university governance, a later era seemed to be refusing the threat of educational eviction.

In our current moment, I find myself most in need of artistic practices that model new forms of institutional care rather than old idioms of institutional disruption, art that focuses us – not on the ‘exit’—but on the long, hard practice of sticking around. I wager that therein lies our best hope for a general creativity.

Question 3: On the Ethos of Radical Scholarship

Here are three points on the ethos of radical scholarship.

- PARTICIPATION The radical intentions of Left scholarship are undermined by the material conditions which permit this scholarship to exist, in whatever form – from the classroom to the publicly available text. Radical scholarship is produced in conditions of adversity: it is made real under the overarching reality of the wage, if you are lucky. If you are not lucky, you are producing such scholarship as free, unremunerated labour, as what Hito Steyerl has called an ‘occupation’, or as your ‘non-job’, glamorised as textual activism. For anyone who is locked into wage slavery can imagine what the conditions of academic wage slavery are: suppressed wages for decades (nowadays cuts are announced through a simple email sent by Human Resources); ‘old school’ feminisation of labour in terms of the core values that reproduce the academia (docility, submissiveness, acceptance of ever-new top-down demands); a promotion system where you can only expect a better title (unless you convert yourself into a ‘top manager’ and give up producing radical scholarship); subjugation to endless metrics (increasingly pretending to assess the social impact of such radical scholarship); atomisation of performance (serial appraisals where you are classified as over- or under-performing as a productive radical scholar); the existential decision to have children or not (use contraception, it’s hard to deliver radical scholarship when exhausted after care labour); working into the night, swallowing the occasional or regular amphetamine to stay awake and alert to radicalness (thought of upgrading to cocaine but your salary is prohibitive?); labour mobility to enter the optimal environment for the circulation of your radical scholarship, as a result of which you give up full citizenship (see EU system of the circulation of academics who cannot vote in the national elections of their ‘host’ country); increased surveillance (did you meet any ‘illegal immigrants’ for the purposes of delivering radical scholarship?); a full-on attack on the humanities (no funding); providing free labour to academic publishers for the privilege of seeing your radical scholarship printed (there are penalties if you don’t); disseminating your and others’ radical scholarship to customers (formerly ‘students’); immersion in fierce competition for the distinction of being a radical scholar (are you proud to be ‘better’ than others, to beat your opponents to that job, to have your paper ‘accepted’?). And these are just some of the defining features of the sector where ‘radical scholarship’ is authored, debated and taught. Indeed, Yates McKee is right to argue that the arts and the academia are close. The premise of this closeness is the willful yet coerced participation in reproducing the commons of oppression. The premise of closeness is a closure. It is the closure brought upon us by the fact that we do not own the means of our reproduction even if we are deluded to think that we own the means of our production – our ‘intellect’ and ‘skills’ - even framed as ‘deskilling’. We could begin spitting on radical scholarship’s grave, Carla Lonzi, except radical scholarship can make us pass for ‘human capital’.

- DENIAL Following from this brief account of the material conditions where radical scholarship is made, Point 2 cannot but be as follows: the Left has the theory, the Right has the practice. Or as put by a precarious colleague, the Left has the struggle, the Right does the winning. There is no doubt that the Left is in denial about the fact that it produces mountains of radical scholarship, endlessly refining the details of its revolutionary programs. It keeps doing it. We can hardly catch up with what is out there. The blogosphere has expanded the Kingdom of Radical Scholarship immensely. In the meantime, the Right is winning elections, occasionally camouflaged as the Left – need I say how everything turns into social democracy at best? In its slow (or, at times, fashionably accelerated) slide to defeat throughout the 20th century, the Left thought it was a radical idea to invest more in bypassing the state, in ignoring the enemy and in building democracy from below. Yet what we have seen up to now is that this DIY democracy tends to remain below – below and far away from the ‘table of negotiations’ where decisions affecting billions, divided into admin-friendly millions, are made. The voters of Europe have sent to the negotiation table the Right to protect borders: the UK borders from Polish workers, the Polish borders from non-European workers (refugees will need jobs). Is radical scholarship preventing the election of a new generation of fascists in Europe? As for America, does not the post-Occupy condition also include Donald Trump? Surely, I am being reductive. Yet I am not bitter and disappointed: the struggle goes on. Indeed. But it goes on, whether we like it or not, as the outcome of real antagonisms. And why, as the struggle goes on, the Left continues losing? In the best case scenario, the radical Left (and its scholarship, which is not one) is outsmarted by the radical ‘Centre’ – which sends good President Obama, and will he be missed, to argue against Brexit on the grounds that the TTIP is good for the people of Europe. There’s some economic surrealism of consequence! What is the power of radical scholarship against this? Across disciplines, radical scholarship has provided all the data of injustice and dispossession. But so has The World Bank – just download for free its gender & work files, the piles of data, available to the collective intellect. Art has also produced social knowledge – and it is certainly embodying the very knowledge of precarity in its armies of surplus labour that is not even always acknowledged as proper labour or proper surplus. Yet The World Bank and the European think tanks do not just produce radical scholarship (or at least data), they also have the means and power to implement. Though local examples may vary, radical scholarship on the whole lacks the means to implement on the basis of its radical findings. And so does art, often however self-entertaining (and entertaining us with) the illusion that because it is executed at the site of ‘real’ social relations (unlike novels, we have to go to the streets or galleries to experience ‘art’), it also has the power to implement. This is wrong. At best, art, like radical scholarship, has the power to challenge, expose and disaffirm. It is not the same as the power of implementing.

- SURVIVAL Radical scholarship and art are joined by their efforts to survive. They have therefore pledged to usefulness. They have extremely sophisticated tactics. But still, they are both pulled in the direction of ‘general creativity’, a pool of ‘innovative doing’ typically dominated by capital’s production needs that regulate and define ever-new fields of specialised practice. It may be true, as Susan Buck-Morss said years back, that art as known through the years of rule of the bourgeoisie is dead, kept artificially alive through the institution. The ‘institution’ is a many-headed monster – one of its heads being ‘us’. But just one. ‘We are the institution’, said Andrea Fraser, but it is not entirely true. In most cases, we are not the institution. We are not the Eurogroup or the ECB or Sotheby’s or the University management or the law firms that secure the wealth of the 1%. We are not the lobbyists or the mafia capitalists. We are not the banks. We exist in a struggle against these and many other institutions. Has the post-Occupy condition generated institutions that can lead this struggle? Can there be institutions that lead this struggle but which do not disperse into a cluster of new separatisms that will, one day, be studied by customers in classrooms as the utopian canon of the early 21st century or, worse, not be studied at all? If so, how will these institutions perform a mass exodus from the dominant conditions of production? For we know that if we stay, we (art and radical scholarship) will not survive. We know that capital commands huge power of biopolitical experimentation on whether we can survive. “How much can we cut wages and pensions? Who else can be drawn into the identity of the unemployed worker? How much pepper spray can we use without everyone revolting? Lets see!”, says capital. We know we are dragged into real subsumption, and that this will mean a transition from total to totalitarian production. Please read Hans Fallada’s novel Alone in Berlin (1947) about the Berlin workers under Hitler and tell me what this intense-production regime, under constant threat and fear, reminds you of. There can be no part-time exodus. I am sorry to say, contra Gramsci, there is no passive revolution. If there had been, we wouldn’t be under the hegemony and domination of capital. The Black Panthers would not have been defeated while New Age environmental radicalism was being promoted as an acceptable ‘alternative’. Communisation theory can only exist as theory, at least on the grounds of empirical evidence so far. The revolution may be a matter of simultaneity but one necessarily executed in material space. It does not need the state-form, it needs the geography of a state. Better if such geography would be the size of a continent. The revolution can’t claim this geography for now, and this is because the state commands the power of violence that dissolved Occupy and anything like Occupy – to paraphrase Greg Sholette (who only said this about Occupy). So, when McKee talks about the ‘strike’ and its ‘heterodox’ variations, things get interesting. Is it then the case that you can’t strike because you are unemployed but you can enter Human Strike or take the streets in support of a General Strike? As regards the latter, we have seen so many General Strikes in Greece but we are still left with the defeat of Left practice (rather than theory, which is doing very well, thank you). One reason was that Europe did not support Greece with a durational transnational General Strike. Neither did North America. As regards Human Strike, I am yet to understand the paradigm as praxis. I understand the concept but not its material realisation. On the contrary, I understand why women have been unable to strike in their care/reproductive labour, even if as a feminist I see this strike as the only possibility for transforming (not reforming) the real base of whatever superstructure. So, to close, can we have a human strike that does not hurt those, rather than what, we love? Can we have our cake and eat it? Can we go to our nuclear nest after Occupy and be in post-Occupy condition? Yes, if we belong to those who got enlightened through and because of Occupy. Welcome to the struggle, comrades. No, if we already knew how capitalism has been winning and therefore see Occupy as an instance in a long, long, long continuum of struggle that is marked by discontinuity. Yet the issue is not for every anti-capitalist generation to re-invent the wheel but to push the wheel forward. The struggle is linear but linearity is not equivalent to ‘progress’. It is linear because we die and others must continue and modes of production exceed our life span. The poorer we are, the sooner we die, the more they exceed it. Which is why we are responsible for turning radical scholarship into the mass radicalisation of everyday opposition for days we will never live. We have a long way to go, and post-Occupy will have taken us further by generating the next Occupy. Preferably, tomorrow morning.

“Radical scholarship” in art history or contemporary art is an oxymoron, from where I sit. I learned a long time ago from Malathi de Althwis, a Sri Lankan feminist activist, trained as an anthropologist at an elite American institution, that there was a world of difference between transformative political action, and academic advancement. She made a choice to go home and work everyday alongside the women whose daily struggle could never be adequately addressed, nor encompassed within academic conversations like this, led by people who could not fathom these women’s real lives. There was nothing radical about her choice to leave American or European academia. It was simply what made sense for her real practice, and her real life.

That said: Look at the means by which this scholarship is all produced and validated. In what way is the system of granting degrees in higher education, which supposedly qualifies people “to speak” actually radical? In what way is the process of getting a book reviewed and published by Verso, Routledge, etc., actually radical? In what way is getting selected for an exhibition, or studied by a PhD student starting her career inherently radical? Who was taking care of the kids while all that writing was getting done? If we can’t honestly ask and answer these sorts of practical questions in every case, then I can’t see how we can talk about whether or not some scholarship is “radical.”

Maybe “radical” is like “the Left” and “avant-garde” to me: something people label themselves after the fact, after the dust settles (and most of the books are written), and someone else is left to sweep up the fallen placards, and other remnants of the encampments. What interests me is how it is always the same people sweeping up, and the same people writing the books. We are NOT all equal on the protest ground. Some of us (insist) on “occupying” more space than others, and some of us have to clean up.

In giving background to this, his third question, Greg mentions me in a parenthetical aside: “(and yes Adeola, sadly [the scholarly books are] mostly written by men who are ‘white’)” Well to me, that fact a big deal, not a mere aside. This unfortunate result has a lot to do with the answers to the questions I posed earlier about “radical” scholarship. If we can’t explain exactly how it keeps happening this way, that the same sorts of people keep their hands firmly on the power to speak, to be heard, well, then I’m not interested in any conversation about how this is “radical” scholarship. Looks like plain old regular scholarship to me: people well-trained in creating truth effects, writing in the language of global power, and in being listened to in specialist circles, steadily citing each other and going about their regular business. @AngelaDimitrakaki and others have pointed out how Leftist “radical” scholarship is powerless compared to Rightist politics. But I can tell you first hand, that Leftist radicalism has many mechanisms to exclude, just as handily as the Right.

And this very system that produces all these “white” “male” “radical” authors is not just capitalist/classist. It’s also racist and sexist to boot, amirite?

It is also because of this racism, sexism and classism, which are all deeply embedded in the processes by which radical art and radical scholarship about radical art are made, that this “radical” branch of the art world, Leftist or not, socially-engaged or not, pro-labor rights in the Gulf or not, remains an often stressful and inhospitable place for me and others like me. As such, I find kinship with the cleaning crew: I didn’t make this mess. I’m just here to sweep up. Sometimes I take a closer look at some of the fallen placards. But this is not my home, and I’m just passing through.

Unlike my teacher, Malathi de Alwis, leaving and “going home” is not an obvious choice for me. Where would I go? It is a much more complicated question for me. I keep traveling, along TransAtlantic routes that my ancestors have been taking for generations. I work outside of this time alone. Like @AngelaDimitrakaki, I work for futures I will not see, but I work simultaneously for pasts that are not even past. My very existence along these routes, in these different times, in these inhospitable spaces, is a revelation, a miracle, actually. Therefore, “radical” is neither here nor there for me. That I can open doors, and speak my truths clearly, and in several languages, of both the powerful and the powerless, despite who is listening: These are victories for myself, and for all the ladies of this brutal TransAtlantic lineage.

Yes, this is mostly correct. While I appreciate the claim for suffering as a badge of honor, assuming that such an identity politics (“outofworkerism” we might call it) is itself a means for change is naive. When it comes to successfully getting those who extracted the wealth, health and opportunity from us and generations to come to give it back, political change requires concrete power much more than symbolic gestures that aim at public shaming. Shutting down factories and ports is powerful, camping in the park is not.

The part that is incorrect is saying that the Aufhebung of the bourgeoisie that Marx labeled “dictatorship of the proletariat” is “simply remaining bourgeois.” It is bourgeois in the sense that it occupies the existing democratic institutions; it is more-than-bourgeois in that it extends the one-person-one-vote principle from the political to the economic sphere much further than it has been heretofore. I would say that the pop-ups referred to are venerable forms of the “new left” not the “modernist left” but with that qualification would agree. The question is really whether the venerable forms of the old left–the party, say, or revolution in the sense of occupying the state–should be considered anew.

maybe this is a little off topic, but I do think it touches on some of the issues in this thread. esp what concerns social-work as art-work as politics as activism etc. the quote, I believe, also touches on the movement in france, and how we, in other cities can organize ourselves & our local communities.

“If [the trade-union movement] cannot reach workers at their workplace, then it must reach them elsewhere. Let the unions open up buildings in the towns and local neighborhoods which people will wish to frequent because they find things they need there, things that interest them, that meet their need for solidarity, for mutual consultation, exchange, personal fulfillment and cultural creation. The trade unions will no longer be able to confine themselves to having forbidding offices sited in cities or big companies and open only at fixed times. They will need to create ‘open centres’ which people can go to late into the night, offering a meeting place, acting as an exchange for services and products, providing courses, conferences, film clubs, repair shops and the like, both for workers and the unemployed - and their families - for people taking time off work, for pensioners, adolescents and young parents, after the fashion of the ‘popular universities’, Britain’s ‘community centers’ or Denmark’s ‘production schools.’ They will have to oppose in a practical fashion the idea that outside paid work there can be only inactivity and boredom; and they will have to offer a positive alternative to the consumption of commercial culture and entertainment. In short, they will have to get back to the traditions of the cooperatives and the associations and circles of working-class culture from which they originally emerged and become a forum where citizens can debate and decide the self-organized activities, the co-operative services and the work projects of common interest which are to be carried out by and for themselves.”

- Andre Gorz, Critique of Economic Reason

As this article on Hip Hop also mentions: “The politics of “having fun” are overlooked by those who imagine early HipHop to have been “apolitical.” While graffiti writing was always fun and only rarely contained explicitly political critiques, it was akin to guerilla warfare in many respects. Originally called “bombing” trains, graffiti writing consisted of the clandestine and “illegal” high-jacking of trains and other public spaces to generate visibility for the invisible.”(https://decolonization.wordpress.com/2015/04/02/hiphops-origins-as-organic-decolonization/#more-744)

we need FUN, communities need something else than (only) struggle, communities in less wealthy neighbourhoods also need to make art, need to express themselves and so on. that is empowering! It remains a mystery to me why art has to be something only the more affluent can afford. radical politics does not come from the bourgeois!!! celebrity anarchism is also a bit boring. Politics is not about who, but about what!

Blake Stimson wrote: “The question is really whether the venerable forms of the old left–the party, say, or revolution in the sense of occupying the state–should be considered anew.”

Here I completely agree with Blake: the question today, again, is not only how to organize resistance into broader coalitions, certainly this is essential, but also what is the relationship between resistance to capital and existing structures of power. Gulf Labor and G.U.L.F. have generated one possible model linking different levels of activism whereby organized oppositional pressure, interventionist tactics, and direct negotiations with institutional power support one another. This is not the same thing of course as building a movement with the aim of gaining power. So the big question remains. As Blake puts it what would a “Left party” look like today and how would it accommodate the strong feelings of decentralization and horizontality that operate across all current forms of political resistance? Perhaps this is a question for some new conversation in the near future? gs

(Afterthought: does a party of pirates and fragmented dark matter actually make a party?)

Following Shannon Jackson’s call for “artistic practices that model new forms of institutional care,” I want to add a few comments about post-Occupy initiatives that are based on building infrastructure for self-organization and mutual aid.

One of the major lessons of Occupy was the importance of physical space for the social reproduction of a movement: space to organize, collaborate, cook, share, sleep, eat.

In the wake of the evictions of Occupy encampments across the country in 2011, many artists and organizers began searching for new spaces to support the activities that had been displaced by the police. As Yates describes in the book, 16 Beaver in Lower Manhattan played an important role before, during, and after OWS, but a single space has limited capacity and a decentralized movement needs a network of spaces. A few examples of spaces that emerged in the post-Occupy context in NYC include: The Base and Mayday Space in Bushwick, Woodbine in Ridgewood, and Interference Archive in Gowanus. All of these new institutions responded in some way to the need for stable spaces for radical culture, education and organizing following OWS.

Where I live in Baltimore, Red Emma’s (a worker-run cooperative radical bookstore and coffeehouse founded in 2004) moved into an expanded space on North Avenue in 2014. In addition to selling books and affordable vegetarian food, locally roasted coffee (as well as beer and wine!), Emma’s hosts educational and cultural events almost every night of the week, runs a free school, and provides a non-exclusive social space for anyone who needs to rest, drink water, use the bathroom, charge their phone, or hang out, regardless of whether you buy something or not. In many ways, Red Emma’s resembles the kind of intensely heterogenous social space that many experienced during Occupy – a convivial and politicized atmosphere of togetherness and conflict.

Red Emma’s co-founder Kate Khatib has referred to the project as a form of “infrastructural activism,” which I understand as akin to the idea of “prefigurative politics” discussed earlier in this conversation. Infrastructural activism is both pragmatic and utopian: constantly negotiating between the administrative concerns of funding, self-management, logistics, and liability; and the desire to enact the more equal and democratic world we dream of in the present. In this way, such work operates a lot like artistic production by first imagining something and then materializing it through a creative process.

In moments of rupture, institutions like Red Emma’s provide infrastructure (space, tools, skills, and relationships based on trust and cooperation) that can be mobilized rapidly, as we have seen during Occupy Sandy and in the days following the Baltimore Uprising, when Red Emma’s served free lunch and functioned as a meeting space for many activists in the city.

On April 12, to mark the one-year anniversary of Freddie Gray’s arrest, a coalition of groups including Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle (LBS) and Friend of a Friend (a prison mentoring program co-founded by former Baltimore Black Panther leader and political prisoner Eddie Conway), occupied a vacant rowhouse in the Sandtown neighborhood of West Baltimore (across the street from the site where Gray was arrested). In a public statement the coalition declared that the reclaimed space, named the Tubman House, has been converted into a community center for meetings, cookouts, clothing giveaways, art workshops and a garden. Fifty years later, the Black Panther Party’s Community Survival Programs remain one of the most relevant and inspiring examples for grassroots organizing today.

The Tubman House presents one model that could be propagated in neighborhoods across the country. In this post-Occupy period of increasing social, economic and ecological crisis, we need to create durable institutions that can sustain the slow work of social movement building over the coming decades and function as spaces of self-organization and mutual aid in moments of rupture.

Such valuable contributions… I find myself agreeing with @shjacks that “sticking around” and developing new (experimentally) institutional practices seems called for - when one has the opportunity to do so. Alan W. Moore @awm13579 also rightly stresses the importance of education and “real” scholarship working to preserve and extend into the present and future past (artistic) acts of critique, solidarity and vision / action.

That to me would imply - in more direct answer to Greg’s question - that our (artists’, curators’, scholars’) realms intersect. Artists (as in this blog) write and museum/uni institutional projects respond to but also add to art, broadly understood (if you allow me a shameless plug, my previous thoughts on this are here: http://www.oratiereeks.nl/upload/pdf/PDF-6174DEF_Oratie_Lerm_WEB.pdf). T.J.Clark kindly responded (in ways echoing Yates McKee’s “end”-game) that this was “a real contribution to the rethinking of art history’s ‘place’ and practice – one that seems so clearly necessary in these strange ‘end times’ we are living through”. So, while I see what @Adeola means, maybe even art history isn’t just one thing (any more? - since Warburg?) either.

Calibrating our joint and cascading discourse (Foucault) and practices to current situations can possibly let art and (its) analysis be part of what makes this collective work live in the world. At the next turn, of course, this can become sterile and commodified.

We need to try to keep caring - and we’re not going to run out of work any time soon…