Image: Still from Cuba: An African Odyssey (2007), dir. Jihan El-Tahri. MPLA.

by Skye Arundhati Thomas

Jihan El-Tahri is an Egyptian-born French filmmaker who began her career as a foreign correspondent covering Middle East politics for the Financial Times, Washington Post, and US News & World Reports. El-Tahri has since produced and directed several documentaries, including the trilogy Egypt’s Modern Pharaohs (2016), which follows the lives of three successive presidents of Egypt: Gamal Abdel Nasser, Anwar Al-Sadat, and Hosni Mubarak; The House of Saud (2004), which looks at Saudi–US relations through portraits of the kingdom’s monarchs; and Behind the Rainbow (2008), which was made during the transition period of a newly independent South Africa. She is also a visual artist, where her work revisits moments of Independence, and decolonization.

Skye Arundhati Thomas: I cannot help but think about your work in relation to Édouard Glissant. In The Quarrel with History, he writes that History has failed us, and that the failure is in what has been erased from collective memory. He writes, “History (with a capital H) ends where the histories of those people once reputed to be without history come together.” For Glissant, the rewriting of dominant historical narratives is the ultimate political act, one to be taken up by artists, filmmakers, musicians, and writers. Your attention to oral histories speaks toward this. Is the rewriting of history something that you actively take up with your work?

Jihan El-Tahri: When I start working on a documentary, the first thing I do is put in a request to declassify documents. After thirty years, you have a right under the Freedom of Information Act in America, in England, and in most Western countries to declassify documents. We don’t have many archives in Egypt, but what we can do is see what was hidden from the Western archives to find the missing links. It should come as no surprise that in the contemporary handling of postcolonial histories many things get lost, where important historical narratives are abandoned by the mainstream for being too messy, and difficult to excavate. So, I start looking for moments that are not the ones that everybody speaks about—because that’s the history we know. I am only interested in the history we don’t know.

When I am declassifying documents I don’t know what I’m looking for, or what I’m going to find. I’ll go to an institutional archive, say, the CIA, and ask for exchanges between certain people during a certain period of time. It’s total and complete guesswork. And after hours of monotonous, administrative labor, I stumble onto something completely wild. Let me give you an example: amongst the classified documents that I was looking through while making Cuba: An African Odyssey (2007), there was this one telegram—just four lines—from a wiretap of a conversation between Fidel Castro and Nikita Khrushchev … And they were just slagging each other off! It was dated 1964, and I thought, hold on a minute, in 1964 Che was in the Congo, as what we think of as a proxy for the Soviet Union, but if Castro and Khrushchev were on such bad terms, why would Che be doing that? I needed an answer. No one was answering it, I even went to the KGB. I had to look where no one had looked before. When Che left for the Congo, he went with 123 soldiers, all of them black, but we don’t know their names because they all had noms de guerre; from what I found these noms de guerre were the Swahili words for 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 … It was impossible to find them remotely, so I decided to go to Cuba.

I started by looking in the black areas in Havana with my assistant and said, okay, let’s knock on doors. And of course he thought I was nuts. We were just walking around asking: hello, do you know anyone who went to war in the Congo with Che? No, no, no … But then at one of the doors a lady answered: yeah, this drunk guy at that bar, he spends his life talking about being with Che in the Congo. So we go to the bar and yes he was drunk, and of course nothing he said made much sense, but he gave us three other names … and once I found one guy, I found almost all of them. I could now ask my question: why was the Soviet Union financing the weapons and arms in the Congo? They replied, a little bit surprised by my question: but the Soviet Union didn’t know we were in the Congo …

I said okay stop. I had just spent two years looking at the story from the perspective that you read, which is of course a Western narrative, and it’s all about proxy wars. But then you’re talking to the guys on the ground and they are telling you a completely different story. No one had ever interviewed them before, and here they were, pulling out photos of their time with Che from under their mattresses. I’m standing there faced with two options: take the easy way out and follow all the books and articles that are available, or break my teeth for another three or four years and see where their side of the story takes me. I opted for the second.

SAT: What does that feel like? Hearing the story no one’s asked about before?

JET: While you’re doing it, it just feels like, where do I go next? How is this coming together? You’re walking in a minefield, and you’re constantly thinking: I could totally mess this up.

SAT: What does failure look like in a context like this?

JET: Like if I had just been given 450,000 euros from a channel to make a film, and then I don’t have a film, or need a few years longer than anticipated to complete it. But I guess failure is also about where you put your own parameters. With the trilogy Egypt’s Modern Pharaohs (2014), things got totally out of hand—there were three revolutions in Egypt while I was working on the films and I was under huge pressure to finish, and under huge pressure, each time, to shift my narrative. But I am careful about where I received my funding, and rarely work with a single funding body for a single film, because then only one body has the power. I divide up that power, and nobody ever has more than 17–20 percent of one film, so no one can actually decide how it works except me. With Cuba: An African Odyssey, I continued for an extra two years, which meant I had to sell my flat and go back to the studio where I lived when I was twenty-two.

But I have to stay with the story; I cannot sustain what I do unless I become completely obsessed with what has been lost. With the documentary work, I am heavily invested in narrative-making, whereas with my visual art I present pieces of evidence in a nonlinear fashion. I work with different formats to leave the viewer with different things to grapple with.

Still from Cuba: An African Odyssey (2007), dir. Jihan El-Tahri. MPLA.

SAT: With your documentary work, is the narrative-making a formal exercise? When thinking about the aesthetic gestures of political images, I always wonder about form, and whether … form can ever be an end in itself?

JET: I’m a believer that form imposes itself on what you’re doing. I used to work at a French film production company called Capa, where I produced a series called 24 Hours. We would take an event over twenty-four hours and follow seven characters with seven cameras for those twenty-four hours. I did fifty of these. I was churning out fifty-two-minute documentaries every week and I got to a point where you could give me any rushes in the world, and I was able to make a film. I had to ask, what am I actually doing? I wasn’t in it for making money, because we all know that doesn’t happen. I think that was a real shift for me. I wanted to make films that impose their content onto me, not the other way around.

When I was doing the Cuban film, for instance, of course it was a Cold War story. And who is the father of the Cold War? Henry Kissinger. I had already interviewed him twice before for previous films, and when I asked again he said he wanted to be paid for the interview. I don’t pay for interviews, and we had this back and forth for a while. But he had already given me two interviews for free and there was no way he was giving me this third one. I had to decide: I’m doing a film on the Cold War and all I need to do is pay Henry Kissinger for his hour, same as I would pay a lawyer, for example. Do I do it? I decided I’m not going to do it. So I picked up my phone and I told him, “Dr. Kissinger, long after you are dead we are still going to tell the story of the Cold War. So if there’s no way of convincing you to do this as just an interview, then I’m going to have to presume you as dead.” Of course, I had a chip on my shoulder, and one of the main players of the story isn’t in my film, but nobody even realizes he is not in it. Because, of course, he doesn’t have to be in the story.

No one can every stop you from telling history. Do your homework properly and you can tell the same story in ten different ways. That’s content. And that’s form.

SAT: It’s almost as though you are assembling your own archive for each film, and so much is dependent on its framing. It provokes the question: can we trust the archivist?

JAT: What do you mean by “trust”? I don’t want to trust the archive. I never say that I am delivering an objective narrative—because I don’t believe that there are objective narratives, there can’t be. History is subjectivity. I think the demand for objectivity can often present generalizations, and the erasure of complexity. In my films, I choose who speaks, I choose who will be the major player, and I choose who will be funny and who won’t be. I even choose who you will get attached to. Maybe what most people want us to do with the archive is to put it in context, but I always ask, whose context is that? The context of the people in the archive? Or the context of the country where these images were being taken, or the context of the cameraperson while they were doing it, or the context of how that history was being translated? I think the archive has a moment in time that you must not betray. And ethics are important here; if you don’t have the ethics or the responsibility of what you’re taking on, you shouldn’t be doing it.

I often use fiction films as archival material. Because in many overtly “political” archives, we are given single frames, or a contact sheet that has no voice, or newsreels of moments of high politics and high political gestures. But if you go to fiction—take the feature films from Egypt in the 1950s for example—you get texture. You get the flavor, the dress code, you get the language. So I don’t want to talk about the 1970s of Anwar Sadat and treat it from the perspective of what Egypt is like in 2015, because it wasn’t the same. In the ’70s people were wearing bell-bottoms and tight pink leather trousers. People had Afros in the street. It’s all about texture and flavor, and the real tensions of historical moments come from the people who lived in it. And so I spend a huge amount of time tracking people down. I’ve done crazy things like find people that everyone thought were dead in the middle of nowhere.

I want to tell stories form a South-South perspective, and I do a lot of legwork to find archives in the south. Obviously I have to use the multinationals too, like AP and Getty, primarily because they have bought most of our archives, but also because often enough the foreign press is the only press with access. But I use such material with caution because the gaze of the camera is a very important perspective to hold to account. When a foreigner comes to my country, what fascinates them is the donkey and the garbage truck, but right next to the donkey and the garbage truck there is a whole other more interesting history.

How do we break orientalist frameworks? Sometimes I am in the middle of my research and I realize that everything that I am going to find is going to be from a Western perspective, and I don’t do it anymore. And yes, I’ve wasted five or six months following those leads but voilà—it’s about choices, and it’s about obsessions.

SAT: Bringing back people from the dead! Such high drama. I would love an example of that.

JET: There was this quite insane moment when I was working on the film The Fifty Years War: Israel and the Arabs (1998). In 1967 the big defeat was in the Egyptian Defense Ministry, and the guy held solely responsible was the Minister of Defense, Shams Badran, who disappeared from public view and was presumed dead. It was the early ’90s, and I was looking for what happened to him, but there was no obituary and all I got were ambiguous answers. I called the Ministry of Defense and asked—they said he must have died, but nobody was giving me a date as to when this guy died. I read somewhere that in around 1974 someone saw him in a queue in a cinema in England. I started looking in England, and I gave myself this chore: every morning I would arrive at my studio and look in the yellow pages at the district directories, and ask, Hello, do you have a Mr. Shams Badran in your district? I got into a habit of doing that and after maybe four or five months, when I reached “P” section, the operator said, Yes, Mr. Shams Badran, I have two numbers for him here. He was in a town near Plymouth, and she gave me a number and an address and I thought well, this is crazy. It felt absurd to just pick up the phone and call him, so I decided to visit him. I travelled with a cameraperson and friend and there we were, standing outside a hardware store in a little town near Plymouth, and there was Shams Badran standing in one of the aisles. The minute I spoke to him he freaked out, he freaked out that I had found him, and it wasn’t plausible to him that I found him in the directory enquiries. But he gave us an interview. And yes—who would have thought he was still alive?

So—never give up. I guess I could have left him out of the story, but I craft my narratives with precision, and often stay with a single link. With the Cuban film for instance, once I found the soldiers, and the research that followed, I knew I couldn’t stray too far from it, and so I opted out of the nonalignment narrative, and I opted out of the Pan-African movement. I couldn’t do the same here—he was crucial.

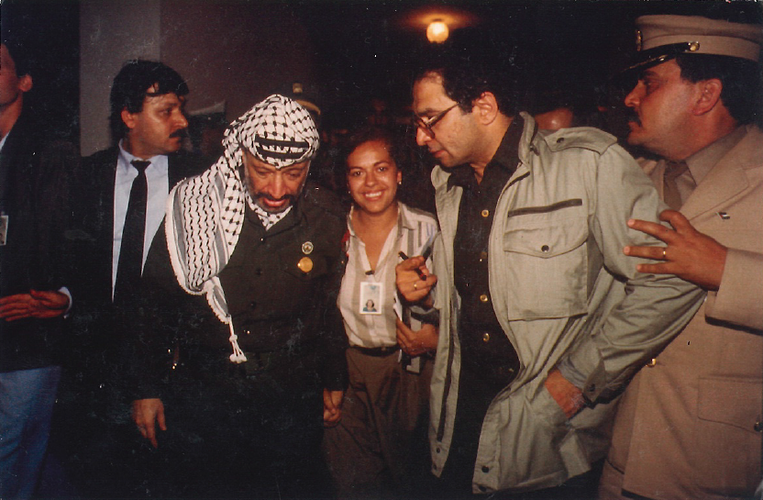

Jihan El-Tahri with Yasser Arafat and Mahmoud Abbas. Magnum Photos.

SAT: I wonder if you could speak more about nonalignment actually. There seems to be a developing interest in the nonalignment movement today, as was the focus of your most recent solo show, “Forward then to … ?” at Clark House Initiative in Mumbai. Is there a particular reason why the current political moment is so ripe for a discussion of the nonaligned period?

JET: I think the interest in nonalignment started much earlier: in 2013 I was in a show at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin curated by Anselm Franke called “After Year Zero,” which tried to bring together stories from African decolonization movements, and the political realignments that happened after the Cold War. This was right after the Arab Spring and it felt like we were at a crossroads for a new world order. I think we are still in that moment in many ways. Since 2011, we seem to be returning to the question—especially in decolonized nation-states—are we really independent? I think to answer this question it is useful to go back to the nonaligned period. For some, it was a moment of great vision, and a moment of hope. For others, it was all bullshit, a moment where celebrity leaders were playing to the cameras, which is not entirely untrue. For me, looking into nonalignment is just one element of looking at what happens during and after decolonization, and at different moments of independence. I think I continue to ask: why didn’t they get it right?

SAT: Perhaps nonalignment provides a moment for the contemporary imagination to locate a certain type of leftist politics, a certain vision for the future, and also failure, in a history that has rarely been revisited. This is also at a time when we are actively discussing the failure of modernism (especially here, in the Indian subcontinent). Perhaps the arrival of modernism in a newly decolonized state and nonalignment are not so separate.

JET: I can’t discuss the failure of modernism when we haven’t defined what modernism really means, particularly for the decolonized state. And yes you’re very right to talk about leftist politics, but I will disagree with the label “leftist politics” because where is the reference for this leftist politics coming from? It’s primarily from a Western perspective. The leaders of the nonaligned countries were manipulating any straight notions of socialism. If you read Khrushchev’s memoirs, for instance, there’s a very interesting bit where he’s on his first trip to Egypt to meet Nasser, but he doesn’t know what to do with Nasser—I mean, Nasser was driving everybody nuts. Khrushchev knew that Nasser was a very important trump card in the Eastern bloc deck, and there he was calling himself a socialist, but what he was doing was not their idea of socialism. He was locking up all the communists, for one. Yet, he was the flag bearer for what many referred to as the “left.”

SAT: Why do you keep returning to the moment of independence?

JET: Well, at the moment of independence, it is as though anything is possible—but it is exactly in the moment of transition, in the transfer of power, that everything falls apart. I had the chance to be able to go to South Africa and live this moment of transition while making the film Behind the Rainbow (2009). I couldn’t help but see the similarities: what happened in South Africa was similar to what happened in Ghana in 1966, and what happened in Egypt in 1954. And just recently Zuma had to resign and the country is in free fall like every other African country. So do you stay with that dream or do you go for the reality of politics? For me this always goes back to the failure of the postcolonial state.

The world has these massive divisions that are being talked about as though they are obvious—but they are not. I am currently thinking a lot about this division between the North of Africa and the South, which to me is completely bewildering because I come from a space that is a space of Pan-Africanism. When did the Sahara become a strip of nothingess? On the contrary, it was where cultures intermingled, where people traded. Timbuktu was a space of cultural interaction. And if you look at all of my films, and all of my work—be it in visual art, film, or radio—I always go back the same questions: how did we mess it up? I can’t let it go. I think also that we are at a historical moment where no one should be replacing us—as postcolonial, subaltern subjects—in telling our stories. Our voices need to reform “the” narrative of History.

×

Skye Arundhati Thomas is a writer and editor based in Mumbai.

All images courtesy of Jihan El-Tahri.