View of Julie Ault’s “afterlife,” Galerie Buchholz, New York, 2015.

These texts were originally published in our sister publication, art-agenda. Double Take is a feature of art-agenda in which two authors review the same exhibition. Written separately, the two texts share the same images and are published below.

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled from Ant Series (time/money), 1988.

—By Pedro Neves Marques

Dear Ted Kaczynski,

It will soon be twenty years since you entered prison. I saw that you finally changed your occupation status to “prisoner” in the Harvard alumni magazine, and that you’ve listed your eight life sentences as “awards.” Controversial as always. Twenty years have done a lot to New York… Luddite that you are, you’d hate it right now. Hell, I’m sure you’d be up for bombing the whole place! The thing is, there are so many tech start-ups, services, and businesses nowadays you wouldn’t know where to begin…

Julie Ault has a solo show at Galerie Buchholz’s new space uptown. I didn’t know that you had corresponded before, but in the show she says so, and who am I not to believe her? I’m sure you must have happened to discuss New York at some point. The city has always been a subject for her work—her life downtown in the 1980s, the artist’s collective Group Material. While Ault’s work has become more intimate, quieter, it’s definitely not mute. It’s just a different politics: of friendship, of details, her own affective archive.

Ault’s archive has traveled some: to the Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Basel; Culturgest, Lisbon (both 2013); and the 2014 Whitney Biennial here in New York. I don’t recall you being mentioned there but here, among a galaxy of personal objects, she has hung a text on the wall about you—a correction to an essay she once wrote for James Benning(2). It’s sitting next to an announcement for the US Marshals’ auction of the Unabomber’s—that is, your—personal belongings. I know you believe this violated your freedom of expression… but it’s a tricky business, you have to admit. They raised money to compensate your victims’ families, after all. Anyway, Julie recalls how the recent discovery of a letter of yours pushed her to rewrite her story. You could say the same for most of the other objects on show, some of which are artworks, others not, including firefighter equipment given to Martin Wong by the FDNY, David Wojnarowicz’s personal magic box, and, just next to your auction announcement, a text by Ault recalling her personal and difficult affection for her grandmother.

As I was saying, things have changed out here. Activists are being targeted by the US state under the umbrella of “domestic threat.” And the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act, passed in 2006, now makes it possible to criminalize any protest against the animal and agro business or even any street act or content that may be experienced as incitement to terrorism. They’re making all of us look like you. Don’t get me wrong, we’re not all against technology as you are—but most of us are deeply concerned with the economy behind it, especially here in New York. The city is being transformed into the East Coast’s Palo Alto but with a typical, apparently edgier, NYC attitude.

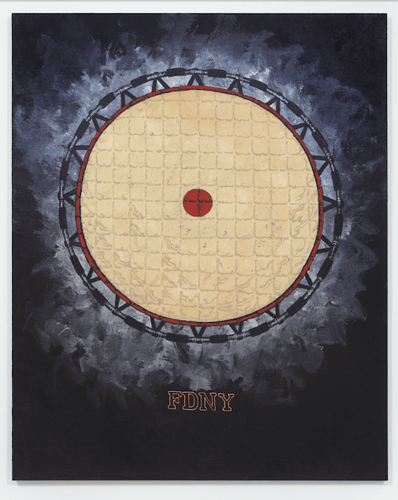

Martin Wong, FDNY, 1998.

What is New York at each moment of Julie’s work? You wouldn’t find an answer in the show, though there are plenty of clues. Wojnarowicz’s late 1980s black-and-white economic photographs with ants marching on loose dollars and clocks (Untitled (Time/Money) from “Ant Series,” 1988) and a buried self-portrait, Untitled (Face in Dirt) (1990). And Wong’s large 1986 painting Untitled (Poetry Storefront), along with his hand-written press release for Semaphore Gallery in 1985, in which he tells this story of this kid Pedro holding a knife to a restaurant owner, failing, and then crying for being a wimp, his bully-friend saying “guess he just doesn’t have the heart for the business,” in a time “when dinner for six was deep fried half & half (gizzards and hearts) Cheetos Ding-Dongs…”. These objects felt to me like specters from a time long gone, New York City ghosts. Well, deep in East Brooklyn and far up in the Bronx where the tech folk don’t reach, pushed farther and farther away from the city center, people are still living the abandoned life described by Wong. The canvas of the old Puerto Rico “storefront” is almost to scale, so that if you dare open the door and enter you can still hear echoes of the “talking coco-nut recite you four-on-the-spot poems for $2”!

Wong’s handwritten press release says much about today’s technological taken-hostage New York you’d hate, Ted. He remembers when, back in 1985, Reverend Roberto Vasquez’s 8th Avenue Pentecostal Church turned into an art bar called “Save the Robots”!(3) A fitting title for the official New York mentality. The bar isn’t there any longer, but if it were, I’d drink a toast to you and Julie. Because save the robots indeed! This city these days will save the algorithm industry, the tech co-working spaces, the up and coming start-ups faster than it would anyone up a 15-story project. Honestly, “robots” in this town are the new white folk. Past segregation does shed light on the future. All of this Julie reminded me of. This city needs people like Julie.

Hoping it’s not too cold in Colorado already. The East Coast has been crazily warm for this time of year—El Niño, apparently.

Martin Wong, Untitled (Poetry Storefront), 1986.

(1) “Unabomber Updates Status in Harvard Alum Magazine,” abc news, 2012. http://abcnews.go.com/US/unabomber-updates-status-harvard-alum-magazine/story?id=16415271

(2) Julie Ault, Two Cabins by James Benning (New York: A.R.T. Press, 2011).

(3) All quotes from the original drawing for press release for Semaphore Gallery, 1985, ink on paper, 27.9 x 21.6 cm. Collection Barry Blindermann.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (Face in Dirt), 1990.

—By Stephen Squibb

The organizations that transformed the human immunodeficiency virus from an economy of death into an expanded freedom in how we receive, understand, and practice sexuality did not always set out to do so. Often their goals were more traditional, even cliché: the securing of funding, the recognition of the obvious, or, in the case of Group Material, to restage a perennial opposition between the instrumental representations of commercial circulation and the imminent iconoclasm of direct democracy. It was AIDS that constellated these archetypical collectivities into a revolutionary sequence capable of unwinding the deep and dangerous institutions of heteronormativity. “Greetings Prophet!” Tony Kushner has the angel address a young man dying, alone in his bed, of AIDS-related illnesses, in the climactic scene of the first part of Angels in America (1993). And sure enough, the last three decades have seen the good news spread far and wide, even if it is in the nature of such victories to resist recognizing themselves as such.

Julie Ault, the longest serving and only continuous member of Group Material, grasps this contradiction beautifully in “afterlife,” currently on view at Galerie Buchholz in New York. How can we memorialize prophets like David Wojnarowicz and Martin Wong without re-inscribing a kind of ultra-phallic monumentality or channeling the very patriarchy which placed their deaths outside the scope of public mourning in the first place? This question of the appropriate material form for this particular historical memory grants Ault’s practice as a curating artist a new kind of power: what is expected from a radical collectivity is entirely groundbreaking under the aegis of a “solo show.” The irony of Group Material’s method was always that for all their procedural radicalism the results often looked remarkably similar: eclectic presentations of various media orbiting around a central theme while loudly announcing their own refusal of authorial singularity, lest the commodity-demon sneak in the back door when nobody was looking. (It did anyway, it always does. There will still be commodities after the revolution, it’s just that labor-power won’t be sold like one.) The same is true here, but with the seemingly conservative addition of Ault in the position of the artist/author. The effect, however, is to recover the radicalism of the method in a new and exciting way. Would that all gallery artists possessed the freedom of assembly that the Group Material archive grants Julie Ault! “afterlife” is a subjective approach to the objective history of a revolution in subjectivity. This feels right.

The first work we encounter is Martin Wong’s FDNY (1988), one of a number of works he painted about his beloved firemen. Lots of people love firemen, of course, and New Yorkers in particular, but when Wong painted two of them kissing in Big Heat (1988) he dramatized both the distance and the similarity between the public’s love of fireman and his own. If we all like kissing, and we all like firemen, what’s wrong with two fireman kissing? It’s the kind of playfully powerful juxtaposition that would come to be associated with another Group Material member, Félix González-Torres. FDNY depicts a kind of trampoline that the department used to catch people jumping from a burning building. A life-saving instrument deployed as a public service, the trampoline is the perfect antithesis of the public response to the burning building called HIV, a response that arrived too slow to save any of the 500,000 Americans who would die of AIDS-related illnesses by 2005.

View of Julie Ault’s “afterlife,” Galerie Buchholz, New York, 2015.

Diagonally opposite of Wong, literally and figuratively, is Wojnarowicz’s Untitled (Time/Money) from the “Ant Series” also from 1988, a photograph of ants crawling in the dirt around some coins and a watch face. Like so much of Wojnarowicz’s work, it’s a timeless image that nevertheless manages to capture the righteous anger of the generation that produced it. Ault’s decision to alternate work by Wong and Wojnarowicz with archival artifacts of both—fire gear given to Wong by friends, Wojnarowicz’s calendar and his gift-shop Wunderkammer “Magic Box”—summons the competing historical and aesthetic injunctions of the exhibition format, actively crossing and re-crossing the boundary between memorial and intervention.

Ault is well aware of her own ambiguous position in this process, which she captures nicely by hanging a section from a Janet Malcom essay about the poet Ted Hughes(1) on the wall, which concerns Hughes’ revisions to an introduction he wrote to a book of Sylvia Plath’s, his late wife. In the early version, Hughes uses the first person in relaying his decision to burn Plath’s final notebooks; in the latter, the decision becomes “her husband’s” as though it was somehow other than his own. At some point in the intervening years Hughes stopped being the subject of history and instead became its curator—charged not with shaping history but preserving it—or rather, with shaping it by preserving it.

David Wojnarowicz, Magic Box, undated.

Ault clearly feels herself to be navigating a similar competition between implication and responsibility, which she accompanies by including a number of small works by the poet laureate of material memory, Danh Vo. The most successful is Snowfall, Northern Sierras, 1847 (2014) a picture of the notches cut into a tree by the Donner expedition to record the height of the snowfall which trapped them, leading some members of the party to resort to cannibalism to survive. We only learn that this is what we are looking at, however, by Ault’s further inclusion of Stumps cut by Donner Party in 1846, Summit Valley, a stereograph of the original image by Alfred A. Hart from 1868. The cannibalism involved in the construction of history is not always immediately evident, Ault avers; and it can seem almost peaceful from a distance, like snow falling on mountains.

(1) Janet Malcolm, “The Silent Woman. Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes,” (New York: Vintage, 1995).

Pedro Neves Marques is an artist and writer living in New York.

Stephen Squibb is intimately familiar with the highways linking Brooklyn, New York with Cambridge, Massachusetts.