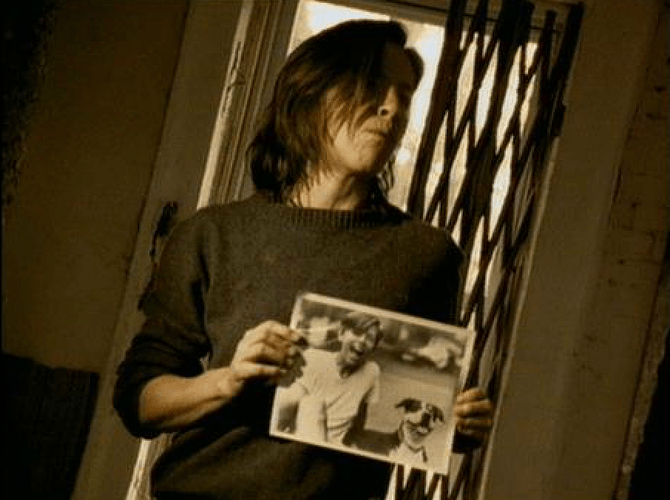

We conclude the evening with a screening of Anton Vidokle’s forthcoming film, Immortality and Resurrection for All!, which draws influence from an essay in Avant-Garde Museology: “The Museum, Its Meaning and Mission” (c. 1880) by Nikolai Fedorov. Federov’s long text is far too hydra-headed to summarize, but one quote is particularly relevant to Vidokle’s film:

“The silence of the grave, the stillness of a cemetery, is the main feature of the present day museum, which is the total opposite of the lively, production trade city, where it is generally located […] here we see a kind of protest against death, a struggle against destructive forces, and as long as museums exist, the victory of death is not yet fully decided. That’s why a museum is not just a cemetery, because it holds not only decayed bodies, but also souls” (132).

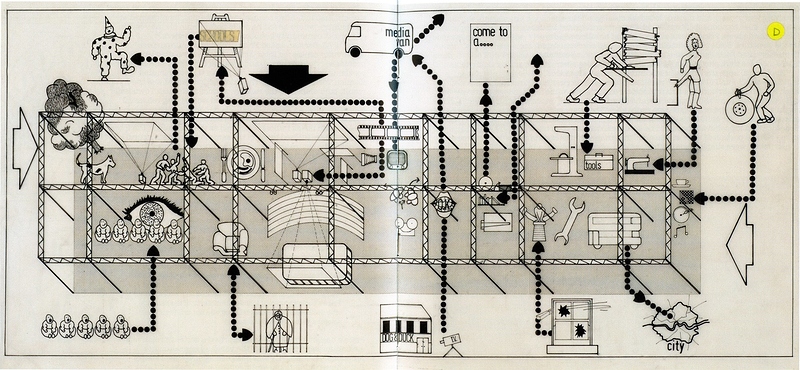

In a conversation with Zhilyaev, published in e-flux journal #71 (March 2016), Vidokle notes that “[f]or Fedorov, the museum is a key institution in society, unique insofar as it’s the only place that does not produce progress (which for him implies an erasure of the past), but rather cares for the past. He felt that museums needed to be radicalized such that they would not merely collect and preserve artifacts and images, but also preserve and recover life itself—resurrect the past. In this sense, museums should become factories of resurrection.”

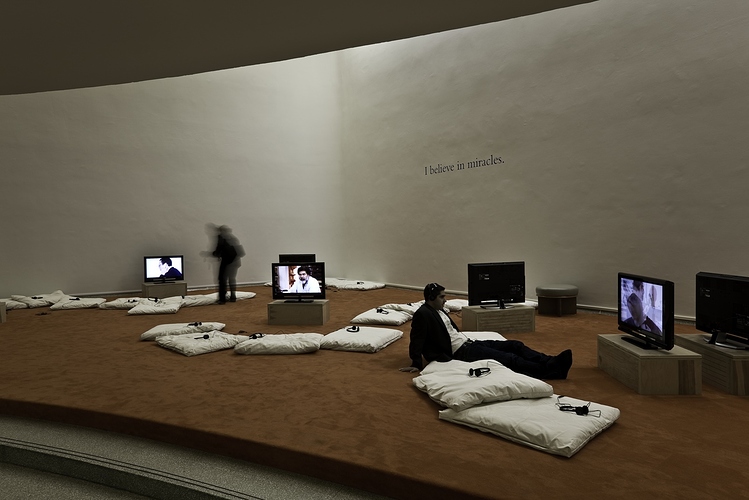

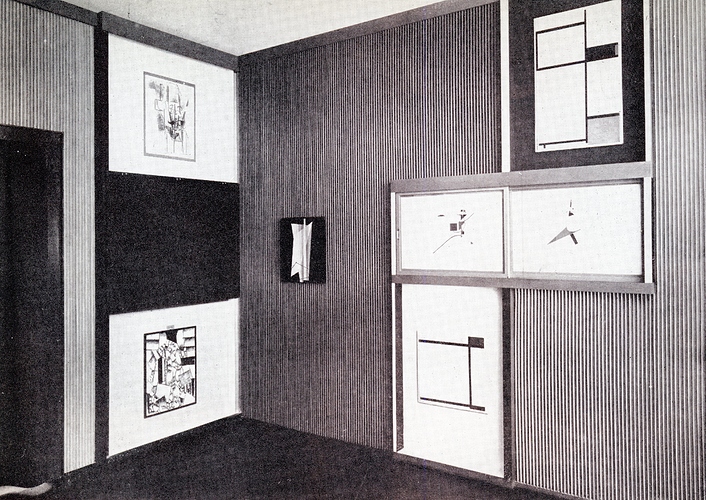

Vidokle’s film unfolds across several institutions in Russia—the State Tretyakov Gallery, the Moscow Zoological Museum, the Lenin Library, and the Museum of Revolution—and features Zhilyaev, members of the present-day Fedorov Library in Moscow, and others. As a voiceover offers abstract reflections on the museum—many resonating with Fedorov’s essay—the camera moves through these institutions, capturing visitors and staff in suspended contemplation (or outright mummification); doing bibliographic and museological work; and speaking in the manner of the voiceover. However one interprets this mesmerizing film, it offers a response both to Groys and Fedorov: depicting institutions as preservationist sites for unknown futures, and imagining the museum as “a soul depository” (133).

That’s a good stopping point for a stimulating first night of Avant Museology. My buddies Erica and João will pick things up tomorrow.

Over and out,

Tyler