Dear friend,

This is the first note I’ve written for the Letters against Separation project. Usually I start with my name: it’s Furqat. In this case, my name is actually quite relevant, as Furqat means separation in Arabic. Nice to meet you.

I was named after the prominent Uzbek poet Zakirjan Furqat. Furqat was not even his real name, it was his pseudonym. He is one of the last poets to write in old Uzbek, also called the Chigatay language. Most of his poems are incomprehensible to me, although he died only a century ago. He witnessed and, in a sense, provoked the creation of the modern Uzbek language especially through his contributions to newspapers and literary magazines. He was a vocal advocate of modernisation and saw the Russian language as one of its entry points for his compatriots. He thought that through colonial institutions like schools and libraries Uzbeks could gain access to modern science and culture. I’m still not sure why he chose such a sad pseudonym, but maybe it was a premonition; his name defined his entire life.

In 1891 Furqat left Tashkent and set off on a journey from which he never returned. Samarkand – Ashgabat – Baku – Batumi – Istanbul – Mecca – Jeddah – Medina – Bombey – Srinagar – Lhasa – Yarkand. I’m still searching for the full list of places he visited, but the fact is he ended up in the Xinjiang province of China, mostly inhabited by Uygurs who share the same linguistic roots as my people. Furqat kept on sending letters to his homeland with his new poems and articles. They say that he had reevaluated his attitude towards the colonial rule of the Russian empire and that’s why the authorities never wanted him to come back. When Furqat initially chose his pseudonym it was meant to mean separation from a person, or being lovesick but the name actualized itself into a new meaning, that of separation from home, or being homesick. Furqat stayed in Yarkand until his death in 1909.

Poster for a soviet film Furqat (1959)

I’m in Tashkent now. Local authorities have imposed strict self-isolation rules. Public and private transport is not allowed. You can only go out of your home if you need to go to the grocery store or a pharmacy. This situation has me thinking about my home all the time. I’m at my parents house and I feel alienated in this place. They built it when I was already living in Moscow. Now I’m stuck here for almost 40 days and thinking about my ethical position towards my home. What should I do to stop feeling alienated here? This is the only place I can call home, isn’t it?

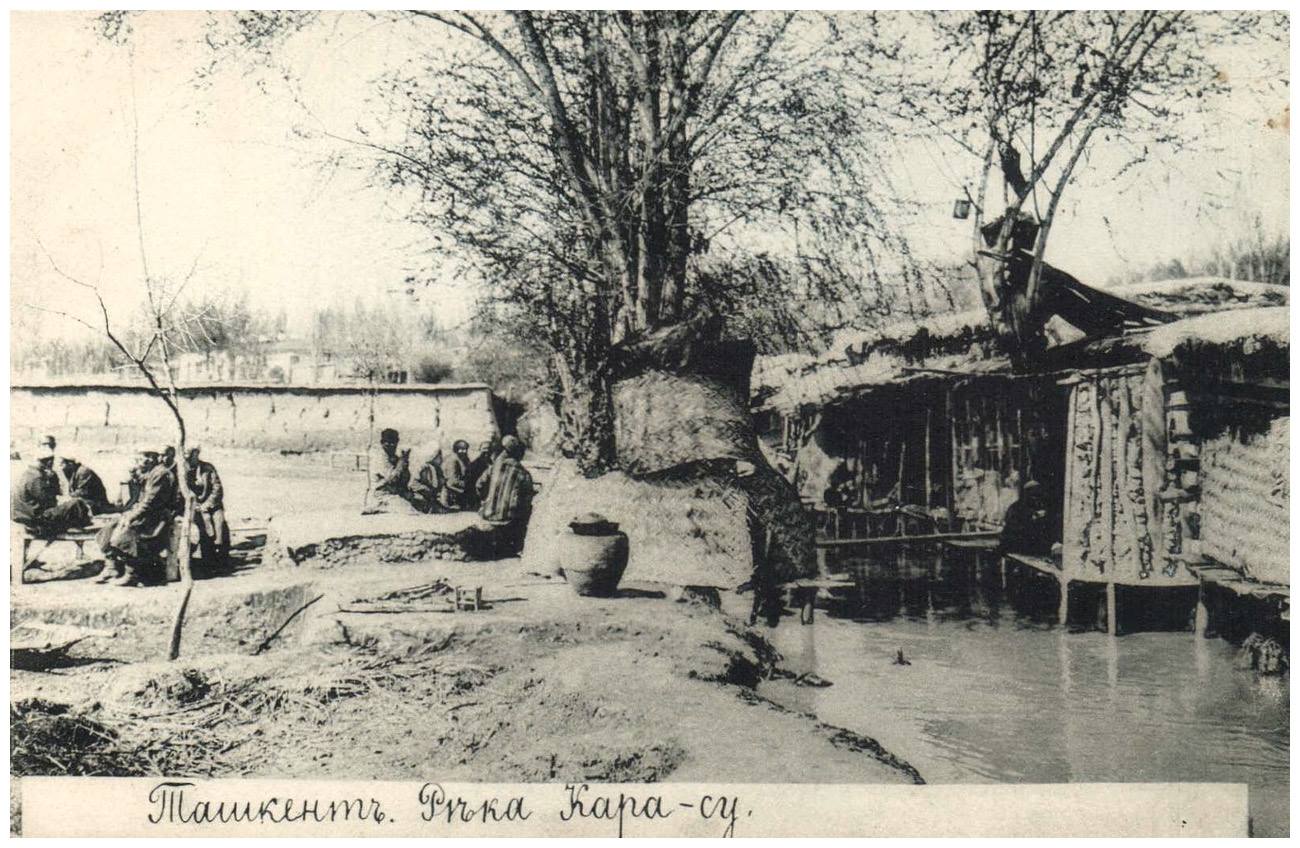

Dear friend, I hope you don’t mind that I’ll be using this situation and task in a practical way. I promise to send 10 letters to you but in those letters I will be researching my home, or at least, I will start my research. What is a Yevrodom, or the arrangement of a traditional Uzbek house? What can I say about the Karasu canal situated near my home, or why the history of Tashkent is the history of water? Maybe I’ll send a daily gastronomic routine in Uzbekistan and talk about how I cooked my first plov with my mom, or detail some of the other (mis)adventures of Furqat in his home. Sounds a bit too ambitious, but I’ll do my best to stick to that plan.

Yours,

Furqat

Tashkent, Uzbekistan. 26 April, 2020