This piece was first presented on February 2, 2017 at Goldsmiths, University of London, as part of “Informatics of Domination,” the Spring 2017 Public Program of the Department of Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths. The program is organized by Zach Blas. For the full program schedule and an introduction by Zach Blas, visit here.

Heather Dewey-Hagborg

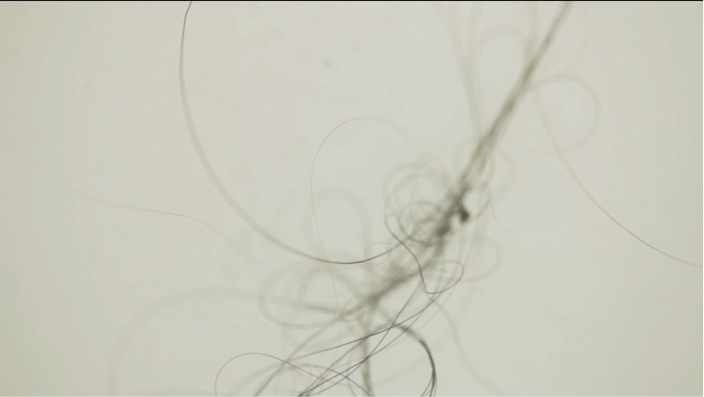

In 2012 I was sitting in therapy and I was staring across the room at this print on the wall, hovering above the therapeutic couch, when I noticed that the glass covering the print was cracked, and there was a hair stuck in the crack. I found myself imagining the patient, who must have had long dark hair, sitting on the couch, leaning back, and getting it caught. It was something I had done countless times myself. I related to this person, this stranger. I wondered who they might be and what they might be like.

When I left I just couldn’t help noticing things all around me, cigarette butts and chewing gum on the sidewalk, hairs on the subway bench, saliva left on the rim of a coffee cup; I started seeing evidence—everywhere. And it occurred to me that the very things that make us human, the messiness of the human body, become a liability as we constantly face the possibility of shedding these traces in public, leaving artifacts which anyone could come along and mine for information.

And so that is exactly what I did.

Stranger Visions

In my project Stranger Visions (2012–13) I obsessively collected those hairs, chewed-up gum, and cigarette butts from the streets, public bathrooms, and waiting rooms of New York City. I extracted DNA from them and I analyzed it to computationally generate life-size, 3-D-printed, full-color portraits representing what those individuals might look like, based on genomic research.

Heather Dewey-Hagborg, Stranger Visions, 2012–13, NYC Sample 6

To do this I looked at traits that are considered fairly well established, like eye color, and I looked at contentious loci correlated with ancestry, where the production of genomic knowledge about populations is highly disputed. I looked at genes that are not often considered controversial but which I think demand further analysis and deconstruction, like sex. And I looked at speculative science, preliminary studies of things like weight, freckling, and facial shape.

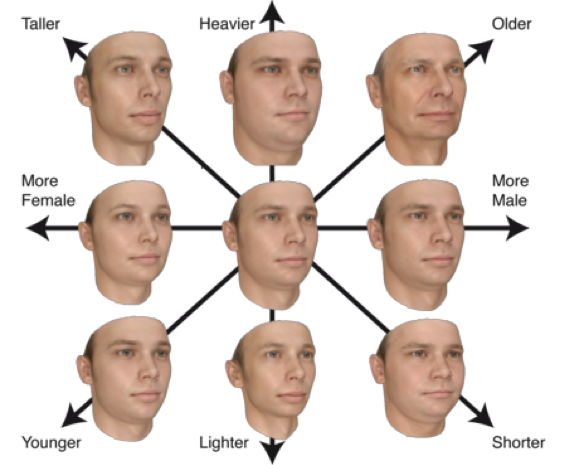

When I started this project I knew next to nothing about genomics or about molecular biology. I had a question—how much can I learn about a stranger from a hair?—but I had no knowledge of how to answer it. I also had almost no money to invest in fancy equipment or lab services. Luckily for me, Genspace, the world’s first community biology lab, had opened two years earlier in downtown Brooklyn. So I brought my samples to Genspace, where I extracted the DNA and sent it for sequencing. Then I analyzed regions that I could extrapolate as correlating with appearance to create a kind of genetic profile, which I used to parameterize a morphable model of a face, extended from an open-source Matlab model, Basel Morphace, which you see below. I appropriated and then retrained and reworked this model, which was normally used for 3-D facial recognition.

Basel Morphace, “Directions of Maximal Variance” →

I generated approximately five randomized variations of each sample and chose my favorite, which I then 3-D printed to produce a life-size, full-color model. So what I was doing was drawing on both established and speculative scientific research to forecast where this technology (DNA phenotyping) was going, to call attention to new vulnerabilities of surveillance but also to the impulse towards genetic determinism—the all-too-common tendency to reduce the complexity of the human to the execution of genetic “code,” as if all we need to do is decipher the code and there we will find ourselves, and our futures, written.

The first sculpture I produced was a self-portrait. People always ask about the accuracy of this kind of technology and the truth is it’s very subjective and varies tremendously case by case. How much do I look like a woman of Northern European ancestry with blue eyes, freckles, and less tendency to be overweight? And what is meant by “looking like”? It’s one thing to see similarities and differences in two faces side by side; it’s another to pick someone out of a crowd as a match.

via Wall Street Journal

The project was intentionally very controversial, from all sides. Stranger Visions enacts a problematic practice to make this very practice visible. It was clear to me that DNA phenotyping research was already happening behind closed laboratory doors. By doing it very publicly, I wanted to demonstrate that this future was just around the corner, and that we needed to start debating it now. And that has been the most interesting part of working on this project: that it broke out of the art context, infiltrated mass and social media, and brought me into all kinds of places I never expected, like public policy meetings about genetic privacy.

Counter-Surveillance

So if Stranger Visions aims to expose the fact that we are entering an era with the potential for mass biological surveillance, the obvious question is, what can we do about it? In 2014 I met Allison Burtch, Aurelia Moser, and Adam Harvey at an art-hack day in Brooklyn. We were all working on different projects related to surveillance and we wanted to make something together. In our collaborative work, DNA Spoofing, we took a playful look at the ways in which anonymity can be enabled in the age of genetic surveillance: DIY techniques, and ways friends can help each other out.

While meant to be playful and humorous, it got me doing some serious research. In 1993 Kary Mullis won the Nobel Prize in chemistry for inventing the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), a method for amplifying subsections of DNA which has become one of the most common techniques in molecular biology and forensics. In 1995 he joked about creating a company called “DN-anonymous” that would sell amplified solutions of DNA that individuals could use for masking genetic identity. While he was joking about actually creating this company, he predicted the someone would actually do this within the next ten years.1

In 2014, drawing on published research about DNA mixtures, I worked in the lab to develop a set of sprays that could be used to wipe away and cover up DNA traces. The artwork Invisible is a working genetic privacy product and set of open-source protocols offered by the imaginary biotechnology company BIOGENFUTURES.

That May I was invited to give a keynote at an industry conference, the Bio-IT World Expo, which would be attended by thousands of professionals. I thought this would be the perfect place to announce my new company and launch our premiere product. After describing Stranger Visions, I said: “You wouldn’t leave your medical records on the subway for just anyone to read. It should be a choice. You should be in control of how you share your information and with whom: be it your email, your phone calls, your text messages, and certainly your genes. That’s why I developed the first ever tool kit to protect your genetic privacy—and it’s called Invisible.”

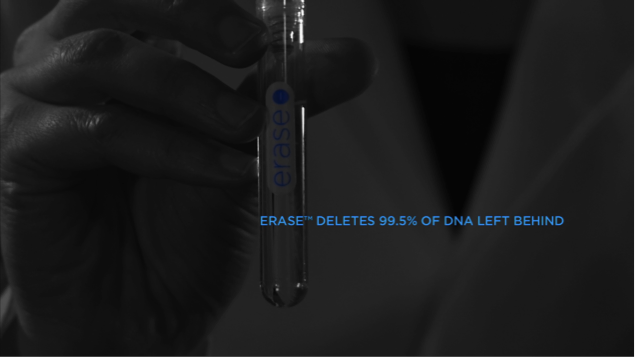

Technically speaking, Invisible is a suite of two complementary products. The Erase spray—bleach and water —wipes away 99.5% of the DNA. But you don’t want to put bleach on everything, so the Replace spray cloaks biological material with DNA noise. Derived from over fifty different DNA sources and utilizing a special preservative to keep DNA stable at room temperature, Replace brings the electronic privacy method of obfuscation to the biological. Erase is good for hard surfaces, while Replace is good for soft or sensitive ones.

Heather Dewey-Hagborg, from Invisible, 2014

On the one hand, Invisible is a functional counter-surveillance product, following in a tradition of such artistic gestures meant to call attention to biosurveillance risks. It is also an exploit insofar as it points out a security vulnerability beyond surveillance in order to interrogate the alleged infallibility of the DNA “gold standard.” It poses the question, could a spray that is easy enough to make in your kitchen at home really help so-called criminals get away with it? Or put another way, if DNA evidence can be hacked, forged, and planted like any other evidence, does it deserve its elevated status?

Speculative Future to Problematic Present

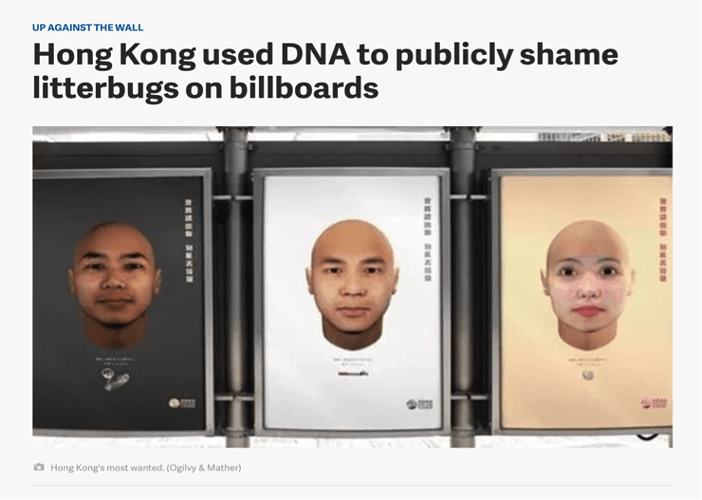

So it’s 2015 and I am working away on my DNA counter-surveillance projects when this happens:

No, I had nothing to do with it. HK Cleanup Challenge, an NGO, partnered with an advertising agency on an ad campaign to call attention to Hong Kong’s littering problem. But in enacting this campaign they hired a real company, Parabon Nanolabs, that had just launched a new service called DNA Snapshot. According to the website of Parabon Nanolabs, DNA Snapshot “is a revolutionary new forensic DNA analysis service that accurately predicts the physical appearance and ancestry of an unknown person from DNA.” Marketed to police departments around the US, Snapshot promises to “produce a detailed Snapshot report and composite profile that includes eye color, skin color, hair color, face morphology, and detailed biogeographic ancestry. Armed with this scientifically objective description, you can conduct your investigation more efficiently and close cases more quickly.”

I expected this in five years, but this was too soon. I knew the science wasn’t ready. After all, I had just been generating handfuls of different possible faces based on DNA and choosing the ones I found artistically appealing. What would Parabon’s criteria be?

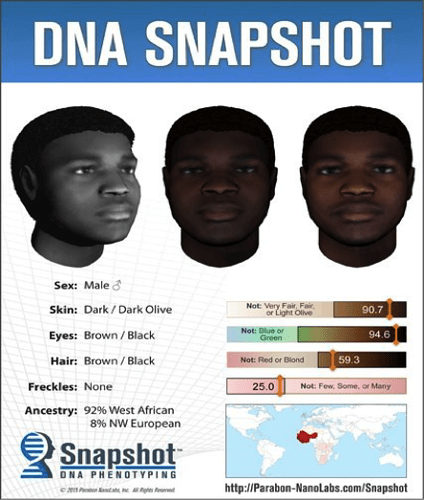

Look closely at this profile they are offering (at great expense) to police departments around the US. What do you see?:

This is not a detailed list of facial features, but rather a portrait of what Parabon considers to be a generic black man. This is a stereotype. The very pressing and very real risk here is that identity categories like race become reduced to data which can be “read” from the body, using black-box algorithms, and that these tools, in the hands of the police, become a new form of racial profiling, propped up by the apparent authority of DNA, of science. If things keep moving in this direction it is entirely likely that in the next five years phenotypic predictions will include an even broader swath of dubiously scientific traits like sexual orientation, intelligence, criminality, and maybe even surname.

So while Stranger Visions began for me as a project to make an invisible risk of surveillance visible, it took me in a new direction as well, to attempt to excavate these kinds of hidden stereotypes that are built into the structure of so many of the tools we use everyday as black-box algorithms. (If you want to read more about this, see my piece “Sci-Fi Crime Drama with a Strong Black Lead” in The New Inquiry.)

Radical Love

In her “Cyborg Manifesto,” Donna Haraway argues that “bodies … are not born; they are made … The various contending biological bodies emerge at the intersection of biological research, writing, and publishing; medical and other business practices; cultural productions of all kinds, including available metaphors and narratives; and technology.” Today, in the wake of Trump and Brexit, when identity has so visibly become a battleground, it is more important than ever that we realize the construction that goes into identity categories like race and sex. We mustn’t allow them to be recast as “nature”—as something written in the “code” of our being, of our bodies. We need to be especially vigilant that biology does not become used as a way to segment people into groups which are subject to differential treatment—to harassment or special forms of attention.

So I was thinking about all these things and then in July 2015 Paper magazine contacted me to ask if I would create a DNA portrait of the American whistleblower Chelsea Manning. Chelsea is currently incarcerated for information she made public that exposed, among many other things, the scale and prevalence of torture and civilian deaths in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Chelsea has been completely isolated from public view since her sentencing hearing in 2013, and due to the military’s harsh policy regarding visitors, virtually no one has actually seen Chelsea Manning since she transitioned from male to female while at the prison. I realized that by using her DNA to give her a public face, I could also give her back some of the visibility that she has been stripped of for years. And I was thrilled at the prospect of working with her.

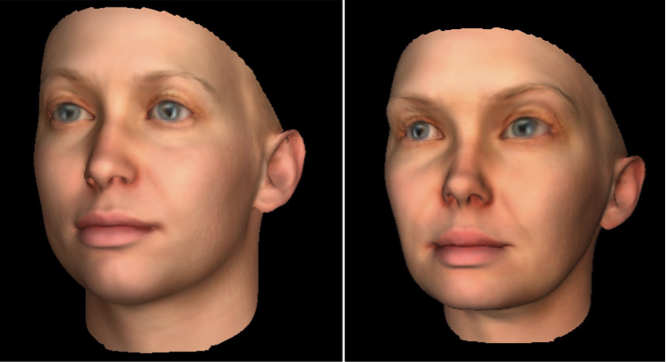

So, the next time Chelsea was getting a haircut she snatched up some hair clippings. Then she swabbed the inside of her cheeks with a Q-Tip and mailed these items out of the prison. I extracted the DNA and sent it for sequencing, and I analyzed it just like in Stranger Visions, but with one crucial difference: I decided not to profile Chelsea’s genetic sex. She was worried about appearing too masculine and I thought her portrait provided a perfect way to call attention to the shortcomings of DNA phenotyping, which relies on stereotyped ideas of what different kinds of faces are supposed to look like—including sex.

The technique that I use allows me to generate lots of different possible versions of a person’s face and then to choose the one I find the most compelling. I generated probably fourteen different Chelseas before settling on the one that spoke to me, and then I generated two variations to represent her: gender neutral, and female (how she self-identifies). These virtual portraits were printed in Paper magazine to accompany the interview with her. The 3-D-printed versions premiered at the World Economic Forum in January of 2016, giving Chelsea Manning a presence at one of the most elite and inaccessible events of the year.

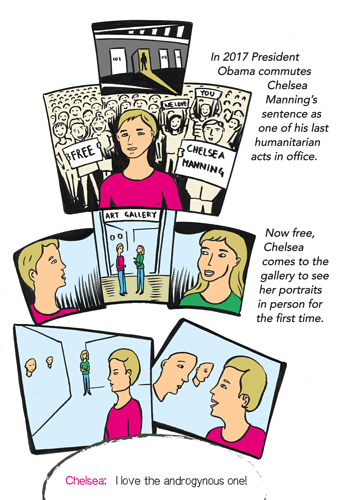

The portraits continue to travel the world, but of course Chelsea still hasn’t seen them in person. I wanted to mail her high-quality 2-D prints of the portraits so she could see them, but I was worried about getting her in trouble. I wasn’t sure what she might or might not be allowed to have. So, I wrote to her first to ask if it was okay. I couldn’t believe her bravery and incredible resilience when she wrote back (almost immediately): “When they chill your speech then they’ve won—so never shut up!  Send me whatever—let the lawyers work the free speech angle if there is a problem! (ACLU rocks!)” So of course I sent her the pictures (and she responded that she really likes the androgynous one).

Send me whatever—let the lawyers work the free speech angle if there is a problem! (ACLU rocks!)” So of course I sent her the pictures (and she responded that she really likes the androgynous one).

Heather Dewey-Hagborg, Radical Love: Chelsea Manning, 2015

The title of the work, Radical Love, attempts to embody some of Chelsea’s spirit, which I have found so inspiring. In her Paper interview she said: “I don’t consider myself a ‘radical.’ Is it radical to seek justice? Is it radical to be rescued by love? It is subversive to be sweet? Instead of trying to be ‘radical,’ I just try to be true to myself! Is it radical to be true to yourself?” Chelsea resists the idea that her or her ideas are “radical,” a term that can be polarizing and alienating. Instead, she points to how incredibly common it is to love and to simply want to be oneself. For me, Radical Love points to a hope of moving past divisive political boundaries, to building community and new forms of knowledge and policy guided by compassion and empathy—a position which is profound in its simplicity.

But the story doesn’t end there. In November of 2016, with Obama’s exit from the White House looming, I wanted to work on something to assist with Chelsea’s campaign for clemency. I was doing a residency at a company called ThoughtWorks and I was approached by an illustrator who worked for them in India named Shoili Kanungo, who saw my artist talk online and wanted to help. Together with Chelsea we worked against all odds—Shoili in India, me in New York, Chelsea in prison—to create a graphic short story in less than two months documenting our collaboration on Radical Love. The story is called Suppressed Images. Everyone said we were crazy, it was pointless, it would never happen. But we did it anyway.

The comic goes over the whole story I’ve been telling here, in abbreviated form. Written as a dialogue between Chelsea and I, drawing on our actual letters and communications, it narrates our process of working together. But it ends with a speculative twist on the last page: Chelsea’s sentence is commuted by President Obama, and she is released and comes to visit an exhibition of her portraits in person. We published the comic in the early morning of Tuesday, January 17. And then that afternoon, it happened: Obama commuted her sentence. (Clearly, Obama likes comics.)

Needless to say, after working with Chelsea for 1.5 years, I was overjoyed and so proud to have been a very small part of the amazing team that fought so hard for her release.

The takeaway: listen to your gut. People always say things are impossible, but every once in a while really positive things do result from a struggle for justice. And we should never stop envisioning and incanting the future we want to see, because those visions have real power.

Biopolitical Art

Radical Love is a work about forced invisibility. In describing our collaboration, Chelsea said: “Our society’s dependence on imagery says a lot about our values. Unfortunately, prisons try very hard to make us inhuman and unreal by denying our image, and thus our existence, to the rest of the world. Imagery has become a kind of proof of existence. Just consider the online refrain ‘pics or it didn’t happen.’” Visibility is an assumption. It comes with certain privileges and power. To be invisible is in a sense to cease to exist. Radical Love attempts to give Chelsea Manning back some of this visibility that has been taken from her.

But visibility can also be perilous. Millions of people in government-operated “criminal” DNA databases around the world are already subject to an especially dangerous form of bio-surveillance, which disproportionately targets minority populations, reflecting the racial disparities which permeate the entire “criminal justice system.”

Because people who are biologically related tend to have more similar DNA profiles, partial DNA database matches widen this discriminatory net to encompass entire families. This means that not only is a person who has been arrested or incarcerated subject to bio-surveillance, but their parents, children, siblings, and possibly even more distant relatives are additionally surveilled by extension. This matters because it turns these people into statistical suspects; their presence in the database, or their connection to someone who is, brands them as suspicious. The aim of these kinds of DNA databases, and their measure of success, is always to re-incarcerate. So from these projects, a complex relationship begins to emerge around visibility and vulnerability, and the ways in which today’s technologies demand visibility as, in Chelsea’s words, “a proof of existence.” Yet that very same proof can be exactly what puts you at risk.

People with records in DNA databases or samples in biobanks are obvious examples of genomically visible populations today. This includes customers of direct-to-consumer genetic tests, research subjects, hospital patients, newborns, arrested or incarcerated individuals, and many others. Further, as I show in Stranger Visions, we are all potentially visible and can be made knowable in this way by anyone who is determined enough. This situation in which visibility is compulsory, in which it can even seem desirable (where we want to make ourselves visible and knowable to power), is described by Foucault and others as biopolitical. It describes the way in which power and knowledge entwine to control and shape us, often in almost imperceptible ways.

What I think we need then is a form of biopolitical art which utilizes visuality to expose and undermine the paradox of visibility—a form of art which operates in seemingly contradictory ways, to make the disappeared visible and the apparatus of visibility problematic. It critiques its own form, and it engages biopolitics at the level of materiality, using the medium itself as a site of artistic research to understand and question its dominant position. If art as institutional critique strives to problematize the institutionalization of art—to make visible the political economy and social relations underpinning the field of art, ranging from galleries and museums to curators, trustees, and sponsors—art as biopolitical critique problematizes the biopolitical apparatus in which it is produced, making visible or experiential the power/knowledge relationship that it relies on. It makes power visible in knowledge—in the sense that it creates objects or experiences of knowledge that question dominant power structures, or it reveals the way in which power is enacted. It opens new ways of thinking and experiencing dynamics of the biopolitical, and hopefully, in doing so, it shows a path not only of resistance, but of something other. It isn’t only about critiquing or deconstructing; it’s also about illuminating alternate visions and parallel knowledges, which opens science, and culture more generally, to a possible future which is truly egalitarian.

×

NOTES

1 William C. Thompson, “Forensic DNA Evidence: The Myth of Infallibility,” in Genetic Explanations: Sense and Nonsense (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013), 252–53.