In The Nation Paul Goldberger reviews the book Welcome to Your World: How the Built Environment Shapes Our Lives by Sarah Williams Goldhagen, which turns to science and psychology to help explain why certain buildings are pleasurable to inhabit, and others painful or distressing. As Goldberger writes, the book departs from accepted wisdom by arguing that “conventional” architecture forms—such as straight lines and symmetrical construction—are by no means universally pleasurable, and that radical architectural forms such as jagged angles can be comforting and disorienting in equal measure. Read an excerpt from the review below, or the full piece here.

But if the experience of sensual satisfaction, of comfort, can sometimes come from daring and unusual buildings, do ordinary things at least guarantee us some degree of comfort as well? In other words, is the plain suburban house OK—satisfying, if not great and important? Here again, Goldhagen makes clear that the priority she places on visual and psychological comfort should not be confused with an acceptance of the everyday or banal. She is impatient with developer-built housing for all the obvious reasons: cheap construction, poor and unsustainable materials, bad room arrangements, social isolation.

“No heed is paid to prevailing winds or to the trajectory of the sun’s rays,” she tells us, arguing that the people in such tract-house developments “lose out…on the well–established psychic and social benefits of being enmeshed in closer and looser networks of people.” To Goldhagen, the residents of these suburban communities have only slightly more control over their environment than do people in the slums of India or on the subway platforms of New York—two other kinds of places that Goldhagen asserts leave their occupants miserable.

It is hard to argue with any of this, or with the underlying premises for Goldhagen’s architectural preferences. She believes, first and foremost, that people need some connection to nature, particularly in terms of natural light, but also in terms of greenery and open space. She also believes they need community, a sense of accessibility, and visual variety and stimulation, although not to the point of confusion and chaos. People respond to patterns and to a human scale; soft forms are better than hard ones, refinement better than crudity. Goldhagen dislikes buildings that might be considered arbitrary or aggressive. But none of these are hard-and-fast rules, and creativity always overrides formulas.

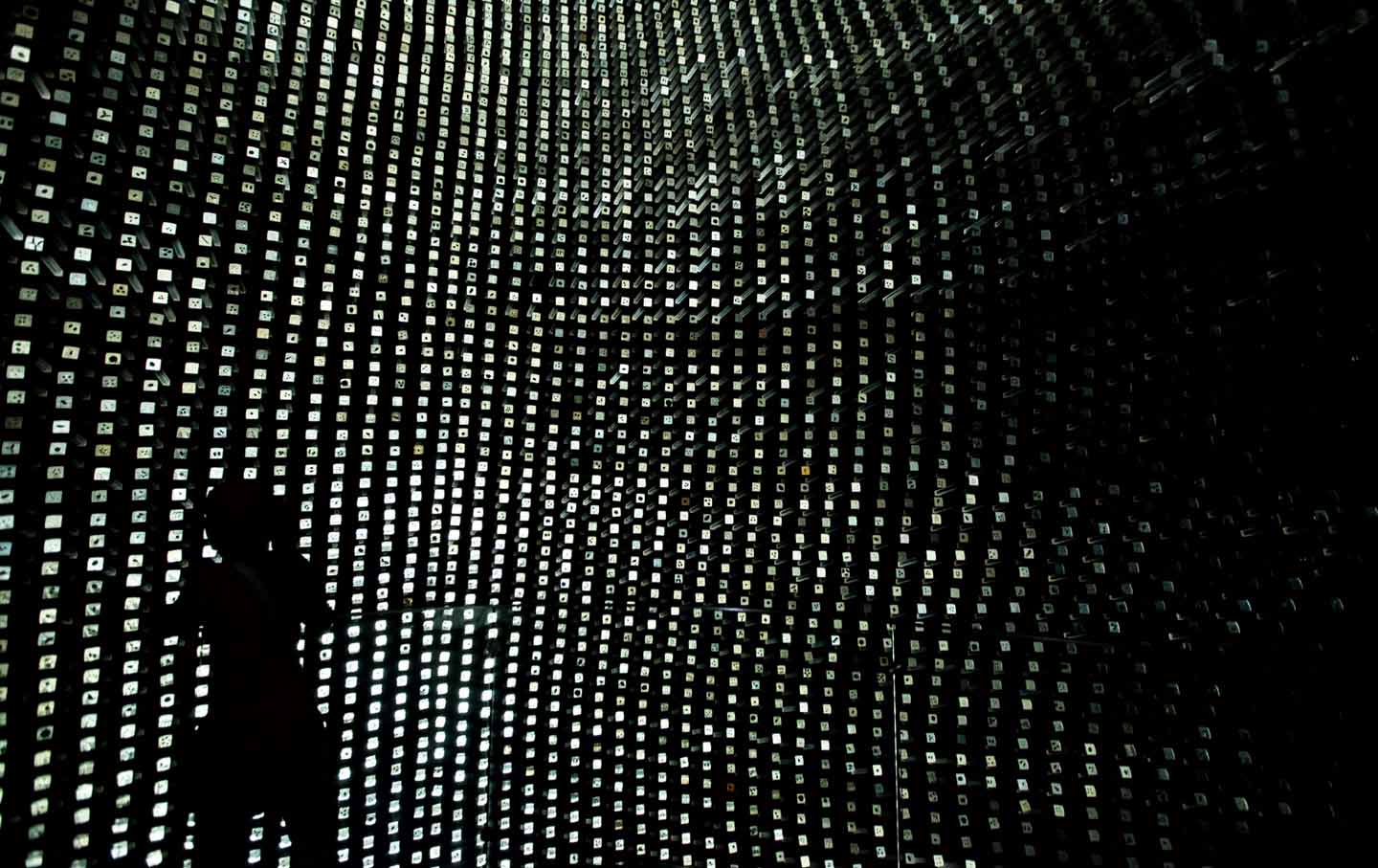

Image via The Nation.