In the current issue of the London Review of Books, Donald MacKenzie reflects on the advent and evolution of Wall Street’s “fear gauge”: the VIX, or Volatility Index, which is supposed to measure the day-to-day volatility of stock markets and therefore warn against financial catastrophes. But as MacKenzie observes, since its inception the VIX has come to be used by investors as a sort of investment vehicle itself, severely undermining its predictive power. According to MacKenzie, “The time for the rest of us to get scared is precisely when market participants aren’t.” Here’s an excerpt from his piece:

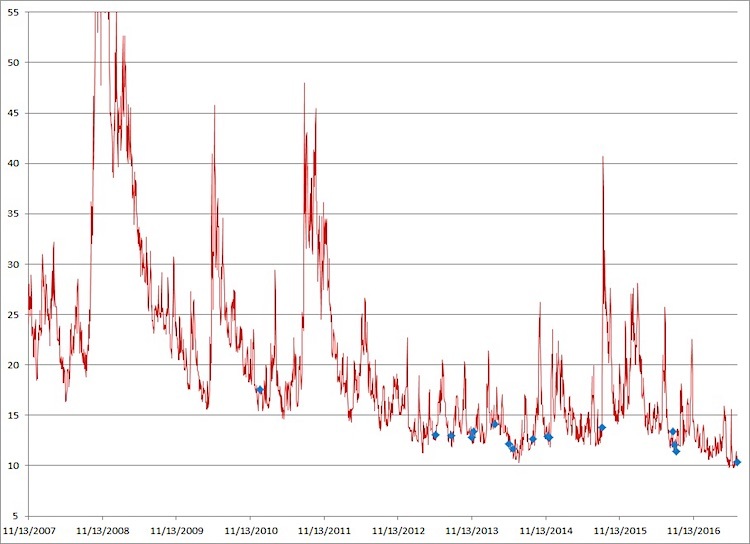

The US economy has gradually recovered from the banking crisis, and the newly legislated tax cuts will further boost corporate profitability. These effects, though, are now ‘priced in’: share prices have already risen to reflect them. Tax cuts aside, the political system remains largely paralysed. The Federal Reserve seems likely to continue raising interest rates, which usually isn’t good news for the price of shares, and is beginning the process of weaning markets off the flood of cheap money that has helped inflate share prices. The tax cuts will most likely increase the Federal deficit. Add in a president who is the very opposite of calm (and who is under FBI investigation), and you might expect the VIX to be approaching the sweaty-palmed 30s. It isn’t. As this issue of the LRB went to press, the VIX was 9.8. It has been low for many months, and shows no clear sign of increasing.

Donald Trump would no doubt attribute the low readings to investors’ confidence in his leadership. But I have my doubts. There is an alternative explanation. Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle is often taken to mean that whenever you measure something, you alter it. In the everyday world, you can usually set this aside: I don’t worry about the effect of the speedometer on how fast my car’s wheels turn or on how its engine runs. You can’t ignore it, though, in economic life. As Charles Goodhart argues, if a measurement device is widely used, it stops being a simple economic speedometer. In the financial markets, it becomes part of how traders think, and can then begin to affect how they act.

Image: VIX Volatility Index, 2007–17. Via seeitmarket.com.