At Public Books, Christina Lupton reviews three books that take different perspectives on the “freedom from work” debate: Rest: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less by Alex Soojung-Kim Pang, Freedom from Work: Embracing Financial Self Help in the United States and Argentina by Daniel Fridman, and No More Work: Why Full Employment Is a Bad Idea James Livingston. In her review, Lupton suggests that discussions around Universal Basic Income and related ideas need to go beyond the work/nonwork dichotomy to ask more nuanced questions about how we would desire to spend our time if work took up a smaller portion of our day. Read an excerpt from the piece below, or the full text here.

Put these three strands of argument together, and it becomes unclear who actually thinks full-time work is a good idea. Is it all of us (on the left, and the right; the prostitutes, the tradesmen, and the professionals), as Livingston believes? Where would this leave Fridman’s subjects, with their longing to be free of work? And what about those really good professionals, who, according to Pang, long ago cracked the trick of napping and taking sabbaticals? Where do female professors at research universities come in here? (Rest does not mention them, but it draws liberally on their cognitive studies.)

Perhaps what we want doesn’t matter if, as Livingston suggests, most sectors seem likely to shrink workloads soon anyway. One technology pundit recently claimed that the unemployment rate will reach 24 percent by 2025. On this basis, No More Work calls the principle of productivity “outmoded, even ridiculous”: “There’s not enough work to go around. We can produce more every year, every month, with less and less labor time. We lost our race with the machine, and we know the robots are coming to take our jobs and steal our emotions.” Livingston is at his most persuasive as a historian, taking us back to forgotten junctures where we knew this better than we do now. In North America in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, he reminds us, advisors and politicians on both sides of the political divide saw this end of work coming.

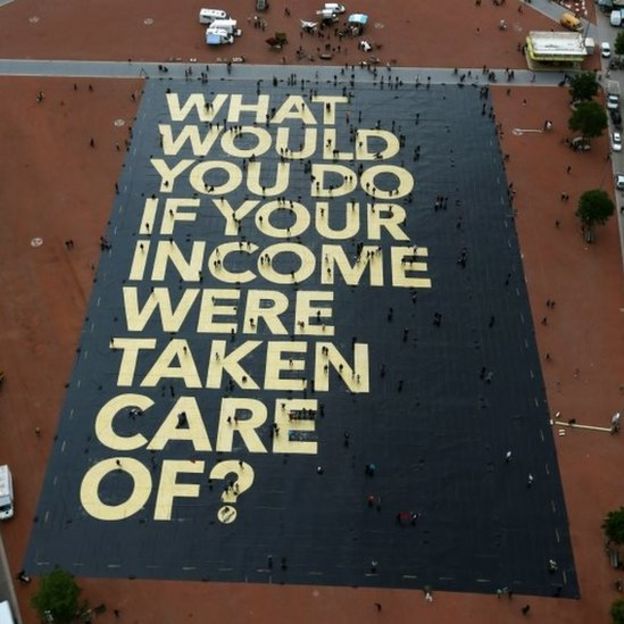

No More Work is more controversially hitched, however, to the movement for a universal basic income (UBI). This movement has gathered steam significantly in Europe since the 1970s. In Switzerland, the proposal to pay everyone a state salary of over 2,000 US dollars a month was recently put to the national vote, and a quarter of the population were in favor. In the Netherlands and in Finland, similar proposals are currently afloat.

Livingston ignores the likelihood that UBI will be granted first in small countries where ethnic nationalism is growing, and that a state where everyone is financially supported is likely to be a very exclusive one. Countries now offering strong support not to work (in the form of paid studentships, parental leave, state pensions, generous sick leave, etc.) are already even more unwelcoming to newcomers than is the US.

Image via BBC.