At Real Life, Phoebe Boatwright compares the image-saturated culture of the US and other developed countries to image culture in Cuba, where access to the internet—and thus to an ocean of social-media-driven images—is restricted. What she finds is that the comparative scarcity of image culture in Cuba creates a richer relationship to those images that can be obtained. Check out an excerpt from the piece below, or read the full text here.

By stepping away from the countries saturated with images, a different sort of potential collectivity through images — one less caught up with consumerism, profit-seeking platforms, and their incentives — can perhaps be perceived more clearly. In Cuba, social media and image proliferation have been suppressed and the media industry is still almost entirely state-controlled or state-sponsored. Economic isolation and Communist Party ideology has militated against the development of individualistic image culture. Fidel Castro had long insisted that all forms of expression be tied to a collective view of the self in relation to society: “The revolutionary puts something above even his aim to be creative spirit. He puts the Revolution above everything else, and the most revolutionary artist will be that one who is prepared to sacrifice even his own artistic vocation for the Revolution” …

In the U.S., the relative absence of censorship and strength of free-speech norms has the paradoxical effect of making the origins of images more obscure: The profusion of images diminishes the comprehensibility of any particular one. All images exist in an increasingly crowded, provisional realm where one can easily be distracted and where an emotional or aesthetic experience can be fleeting. With information proliferating from so many different and often unidentified sources, shaped for so many different purposes — from the official channels of advertising and entertainment, news, and politics to the individually driven channels of social media — meaning becomes more opaque and more elusive. Rather than poor images, we have poor content. The efficacy of fake news stems from this degradation. Image proliferation encourages both uncritical consumption and total skepticism. What is true? Not only are emotional and aesthetic experiences blunted, but any sense of truth is also lost in the din.

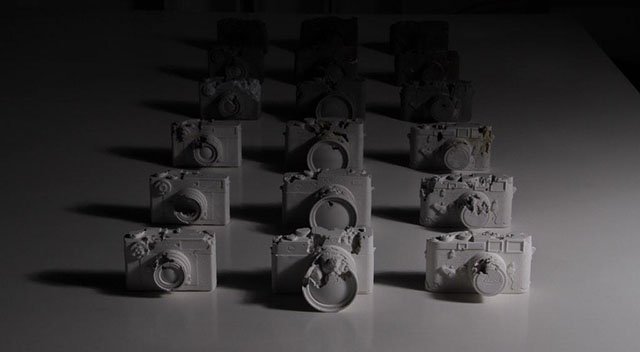

Image: Future Relic by Daniel Arsham. Via Real Life.