SUPERCONVERSATIONS DAY 87: ROBERT LINSLEY RESPONDS TO RAQS MEDIA COLLECTIVE, “A KNOT UNTIED IN TWO PARTS”

#The Cooperative and the Small Proprietor

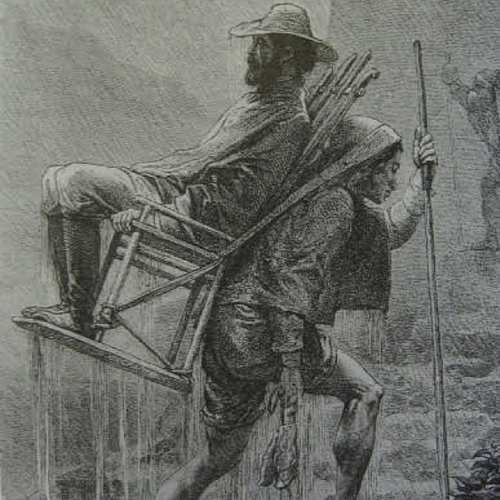

Andean “sillitero” carrying a European across the mountains on his back. If not for the rain, the passenger would probably be reading a book. An image of the artist as manager of their own labour.

Ram Sagar isn’t exactly correct when he says there are no owners. The bank accounts that grow with the profits from his labour belong to particular people, people who know how to hide. From where Ram Sager is standing it may not be possible to see their faces, but critics need to take care not to fall into the familiar Baudrillardian-Foucauldian ecstasy of the social sublime—awe in front of the massive machine of capital that apparently just drives itself and carries us all with it. That’s not a Marxist perspective. Marx believed that humanity controlled its own evolution, even as it mystified that fact to itself. So the dialectic of the joint stock company and the co-operative as two forms of organization of social capital has to do with organicism and control, topics that are also pretty relevant to art.

The question is how can a group of individuals with private motivations and needs act collectively and spontaneously in their own interest? How can they take a direction, together, responding to ever changing conditions, without constant intervention from a leader? How can the interests of the individual and the interests of the collective be identified in a way that does no violence to the individual? Marx didn’t have an answer, but the believers in “free” markets think they have it figured.

The difference between the co-operative and the joint stock company is that in the former the owners are also the workers; that’s very clear and simple. What’s less clear to the co-owners but very clear to capital is that it’s impossible to draw boundaries around any enterprise—the whole human world is a giant co-operative, or joint stock company if you prefer. The different spheres of public and private life haven’t been shattered and sent swirling into the market, they were illusions to begin with. The systems approach, like Marxism, sees the world as it actually is—a totality, a single system of many parts—and also recognizes the utter arbitrariness of any subdivisions within it. Another word for that arbitrariness might be the freedom to create contingent human worlds, and so again art has something to say.

With all that in mind I find that I’m sensitive to the skepticism that Raqs express toward the sole proprietor, or small business owner, or artist as such. Without coming right out and saying it, Raqs seem to hold the standard contemporary view that the artist/individual, or solitary genius, is an outmoded form. This is such an uncritical view that it demands one take a distance.

Today all work is done by teams. Maybe it’s hard for artists who have never done any other kind of work—never worked in a factory, never worked in a technology start-up or in a big office or on a sales team—to have a perspective on this. To critique the artist as a small producer who owns their own tools, sells their goods when and to who they want, works on their own schedule, sets their own goals and strives for a unity of labour and pleasure, of sex and work, as a relic of the 19th Century strikes me as completely blind. The world around us has accomplished that critique more thoroughly than any artist collective ever could. The current trend for artist groups, collectives and teams is in no way a critique of anything, it’s just a surrender to the status quo. If we look at the landscape of work today the artist as individual, heroic or not, is the critical position.

Raqs’s view is a nuanced one, so I’m not taking issue with them, but the thoughts of a collective, like those of an individual, always have some quota of the conventional. And, as it happens, non-conventional thoughts only appear in individual minds. The individual as the generator of differences has not disappeared, but the trend to collective actions accompanies a general flattening or weakening of the power to differentiate. There is even data that tracks a decline in productivity as science has moved away from research by individuals to the team model, and that’s a good parallel with art, closer than manufacturing for example. It seems that today a group is needed to do things once done efficiently by individuals. Human capacities are being lost, so I can’t celebrate the “molecular,” small temporary acts of association—a kind of practice most astutely discussed by Lane Relyea in his recent book Your Everyday Art World. Artist collectives are symptoms of a decline in the critical faculty, in fact they are ideology through and through.

Crudely, in art, as in all labour, there are two positions, the manager or owner and the poor devil who does the work, as Ram Sagar would confirm. Instead of negating this opposition, most artists just internalize the two positions and take them up in turn. An artist comes up with an idea, presumably after market research, and then proceeds to carry it out like any flunky. To give orders to oneself and then diligently carry them out—I don’t know whether such behavior is more painful or ridiculous. The co-operative — meaning the organic, self-motivating, self-controlling social unit, in which the owners are the workers — must be established in the studio and in fact inside the individual artist. All power to the soviets and the worker’s councils! A revolution on the shop floor means liberty for art, if not for the artist. The relation between artist/manager and artist/worker cannot be resolved into something less agonistic, or less costly, without the third term, the artwork itself.

Robert Linsley is an artist who writes from time to time. His work can be seen at http://robertlinsley.com, and his blog is here: http://newabstraction.net His book, with the working title The Future of a Negation: Abstract Art in the Era of Global Conceptualism, will be published by Reaktion in 2016.