On the occasion of the Renaissance Society’s 100th birthday, e-flux conversations will provide live coverage of the Ren’s In. Practice symposium taking place 20-22 November, 2015. Caroline Picard and e-flux conversations Editor Karen Archey will take the live blogging helm. Check out the symposium press release and schedule below.

Download the symposium program booklet here

Download the symposium program booklet here

Download a map of Hyde Park here

Download a map of Hyde Park here

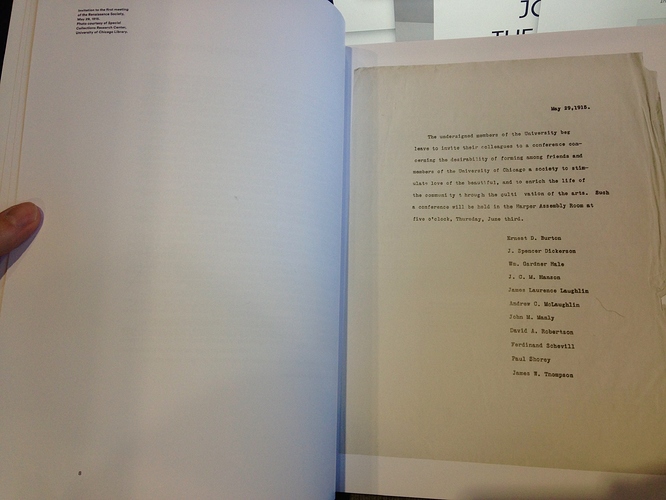

As the Renaissance Society enters our second century, we continue to grapple with a number of questions concerning the past, present, and future of the contemporary art institution. “In. Practice”—a gathering organized on the occasion of the Renaissance Society’s Centennial—offers a series of inquiries anchored in concerns relevant to practitioners from a variety of international contexts and scales.

The “In.” of the title refers not just to institution, but also nods to words like independence, in-betweenness, interaction, intention, and invention, concepts fundamental to these discussions. The event approaches “practice” in both senses of the word: as a way of working developed over a long period, but also as a perpetual experiment into the boundaries of exhibition-making and identity-building.

While registration is now closed, we anticipate that there will be additional seating available on a first-come, first-served basis for each session.

While registration is now closed, we anticipate that there will be additional seating available on a first-come, first-served basis for each session.

SCHEDULE

SCHEDULE

Friday November 20, 5–9pm

Friday night offers early symposium registration, extended hours viewing of Paul McCarthy, Drawings, and the opening reception for Let Us Celebrate While Youth Lingers and Ideas Flow: Archives 1915–2015 at the Gray Center Lab.

Saturday November 21, 10am–5pm

Models and Conditions

The Saturday program addresses global conditions that exert influence over institutions and the production of new works, knowledge, and identity; a number of institutional case studies in functional and theoretical terms; institutional and artistic needs; and the power of the image.

Key questions include: What are the financial, emotional, physical, political, infrastructural, and formal terms that govern the health and survival of artistic practice within an institution? How can institution-building function as a curatorial practice? How do we define the condition of “in-betweenness” and how might that affect the trafficking and understanding of images?

Solveig Øvstebø introduction

Nina Möntmann on the evolving role of art institutions in response to recent global, social, and economic shifts

Sarah Rifky on Beirut (2012–15), an art space in Cairo, Egypt investigating politics, economy, education, ecology, and the arts

Aaron Flint Jamison and Robert Snowden of Yale Union on Yale Union, an art institution in Portland, Oregon founded by artists Jamison and Curtis Knapp in 2011

Park McArthur on needs (What do artists need from institutions, and the inherent difference of the inverse question: What do institutions need from artists?)

Irena Haiduk and Kerry James Marshall in conversation with W.J.T. Mitchell on inclusion, exclusion, and the making of the art historical image canon

Saturday November 21, 8pm

Centennial: A History of the Renaissance Society, 1915–2015 book launch at the Logan Center

Sunday November 22, 10am–3:30pm

Time and Materials

Sunday investigates materiality, both in and out of the artist’s studio; institution as material; the relationship between the origins of conceptualism and ever-evolving modes of production and dissemination; and the manifestation of archival tendencies in artistic research and practice.

Key questions include: How do languages of immateriality and dispersion nest within the institution of tomorrow? What is a non-collecting institution’s relationship to the past and why are archival practices an increasingly compelling subject to artists and curators alike? How do institutions and individuals collaborate to construct a coherent past?

Jordan Stein introduction

William Pope.L in conversation with Anthony Huberman on temporality, power, and institutionalism

Anne Rorimer and Karen Archey in conversation with Hamza Walker on how conceptualism, immateriality, and dispersion exist within the contemporary art institution

Ranjit Hoskote on retaining a critical relationship to narrative, the archive, and the phantom of the art historical

Alberta Mayo on custody, caretaking, and the individual as institution and anomaly

Ranjit Hoskote and Alberta Mayo in conversation with Blake Stimson

“In. Practice” is part of the Renaissance Society’s Centennial program.