After a wonderful Sunday of presentations, discussions, and performances at the Walker, covered here, João Enxuto and Erica Love @EnxutoLove will be at it again on this thread for the culminating Monday of Avant Museology.

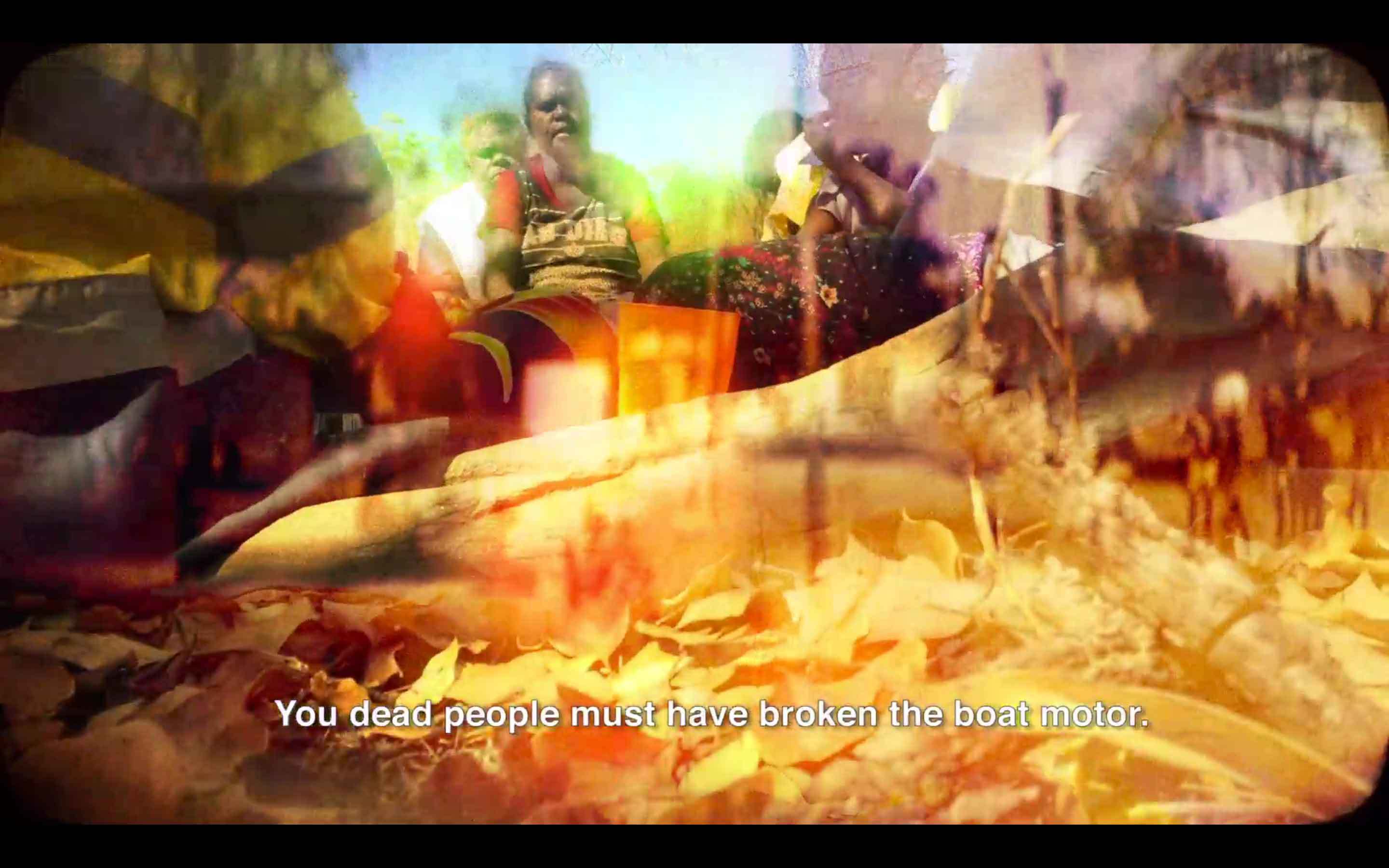

Image: Anton Vidokle, Immortality and Resurrection for All!, 2016. Video, single channel.

Join them for in-sights on the following presentations:

11:00 am | Anton Vidokle

Anton Vidokle will present part of a new film based on Russian Cosmist philosopher Nikolai Fedorov’s 1880 essay “The Museum, Its Meaning and Mission,” included in Avant–Garde Museology. Starring members of the present–day Fedorov Library in Moscow as well as Arseny Zhilyaev, the film was shot last winter at the State Tretyakov Gallery, the Moscow Zoological Museum, the Lenin Library, and the Museum of Revolution. Titled Immortality and Resurrection for All, the film is an artistic interpretation of Fedorov’s universal museum, where immortality and resurrection will be actualized.

11:45 pm | Sohrab Mohebbi

Sohrab Mohebbi’s presentation explores the possibilities of theory as an art form. Proposing a quasi–history, it investigates how artists, and by extension art spaces, contribute to theoretical debates. Drawing upon a number of works, the presentation asks not what theory does for art but what art does for theory, in the lure of what Chris Kraus calls an “atmosphere of meaning.”

1:45 pm | Ane Hjort Guttu and Nisa Mackie

It is an open question as to whether the museum provides the best context for artistic expression, social analysis, and political change. If the prevailing aim is to subvert an existing socioeconomic order, in the “BIG” museum there is risk of subsumption by the dominant hegemony—or worse, a forced double life. Ane Hjort Guttu and Nisa Mackie will engage with this question by interrogating how artists might navigate the super structures that govern the production, circulation, and reception of their work. The dialogue presents the possibility of temporal utopia that often precedes the nexus of personal and political crises. This might take the form of speculation and fantasy, play, abstraction, or true praxis— all of which point to forms of the possible.

2:30 pm | Elizabeth Povinelli

Filmmaking as Perpetual Motion Museum

In 2012, under the auspices of the Karrabing Film Collective, Elizabeth Povinelli and her Indigenous colleagues began making short films as a method of self– organization, social analysis, and alternative imaginaries. The films were residual artifacts of this practice of a living analytics. They were like Hitchcock’s MacGuffin, a plot device that can organize a pursuit whose actual aim is survivance. As objects, however, the films provide storage of an alternative history of the present that can in turn be stored in a future alternative museum. But they threaten to provide a site of social fetishization, as if the central value lay in the aesthetics of the objects rather than the survivance of worlds. How might an avant–garde museum be not a storage bin for anesthetized objects but rather a space for the perpetual exfoliations of alternative worlds?

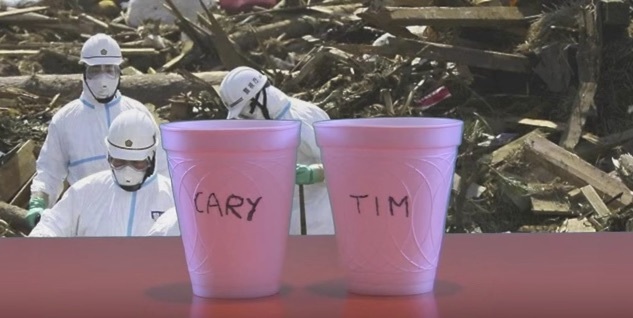

3:45 pm | Cary Wolfe and Timothy Morton

Avant What?

In this freewheeling conversation, Timothy Morton and Cary Wolfe will explore the idea of the “avant” and the various ways in which “avantness” has historically been incarnated in art, literature, music, and culture. Both authors will discuss the relationship of the idea of the avant to their own work and the extent to which it is or isn’t a useful way to think about ideas of time and temporality, newness and oldness, chronology and succession, beforeness and afterness, and the layered, textured, multi–species spaces in which culture (and not just human culture) happens: Morton in relation to his writings on literature, art, music, and ecology in landmark texts such as Ecology Without Nature, The Ecological Thought, Hyperobjects, and Dark Ecology; and Wolfe in relation to his work as both author (Critical Environments, Animal Rites, and What Is Posthumanism?) and founding editor of the Posthumanities series at the University of Minnesota Press.

More on the symposium here.

Immense gratitude to Erica and João, The Walker Art Center, The University of Minnesota Press, and all of the brilliant presenters that made up the two weekends of Avant Museology.

Stay tuned in the near future for the continued life of the talks and ideas presented in the symposium …