Join Erica Love and João Enxuto [@EnxutoLove] on this thread for live responses to Saturday’s presentations during the Avant Museology symposium at the Brooklyn Museum.

Image: Anton Vidokle, Immortality and Resurrection for All!, 2017. HD video. Photo: Ayman Nahle.

Saturday, November 12: 11 am to 8 pm, EST

Live Stream here

11 am – Session introduction

11:05 am—Arseny Zhilyaev

The editor of Avant-Garde Museology reflects upon the main conclusions drawn from his research for the book. Today many contemporary artists uphold the historical avant-garde’s negative attitude toward the museum as an institution for maintaining the class enemy’s order of things. In 1917, with the new social agenda of the Russian Proletarian Revolution, art was transformed from a bourgeois ghetto into a means of production in the service of a new communist society and a new human. Marxist museology appeared to provide a possible solution to the dilemma the historical avant-garde posed for artistic institutions. The display methodology and concept of the post-revolutionary museum drew closer to historical materialist practice, even echoing a number of avant-garde principles. According to Zhilyaev, the final stage in establishing museology as a means of production and a medium for social and human development is best described by the philosophy of Russian Cosmism, which envisioned the museum of art as the ultimate frontier for human expression—based not on social or physical contradictions, but on overcoming any limits imposed by nature or earthbound political or economic orders.

11:45 pm—Molly Nesbit, “Duchamp’s View”

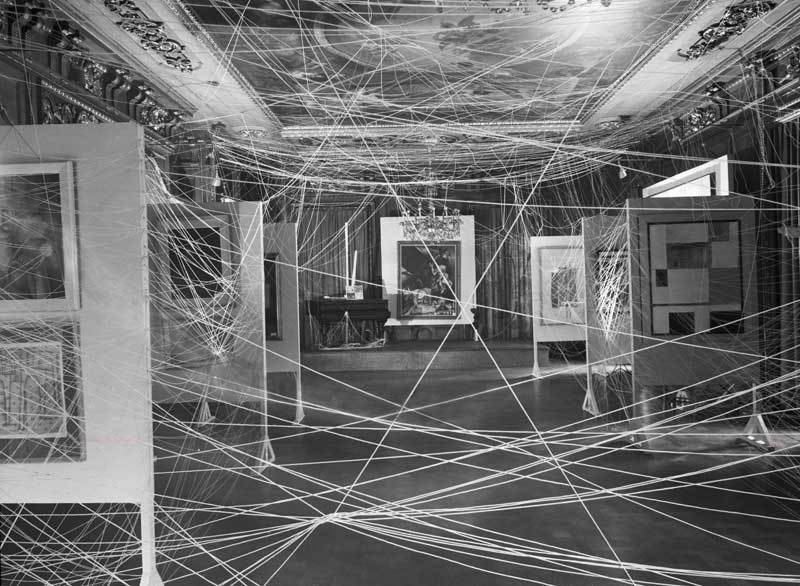

Marcel Duchamp was always considered by his peers to be the outlier, not part of any one avant-garde, and yet setting the benchmarks by which the radicality of their work would be measured. On a few special occasions he designed installations for avant-garde exhibitions, but this was the exception, not the rule. In March 1961, Duchamp told a group of art students at the Philadelphia Museum College of Art that the great artist of tomorrow will go underground. In the draft for this talk, he used the French word maquis. The wider scope of this resistance and Résistance can be seen throughout his work and measured empirically. In his own underground, there was always already a politics casting its shadows over them all.

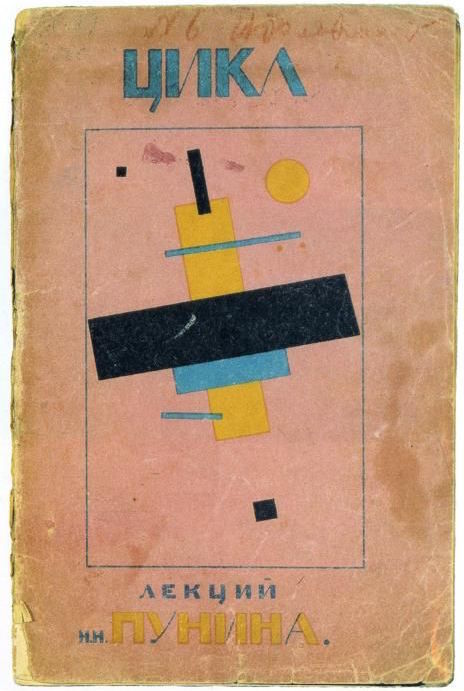

12:25 pm—Nikolay Punin, “The Dead-end of Bourgeois Art”

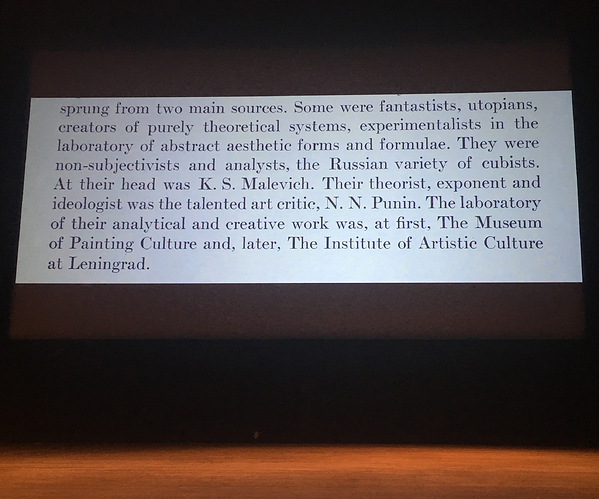

A few years after the Soviet Revolution, some museologists began thinking about the role of art and the art museum in the new socialist society. If socialism is the most advanced society, then its art should be the best, while the art of previous epochs must be considered inferior and presented accordingly. Thus, in the early 1930s, Aleksei Fedorov-Davydov organized several “Marxist exhibitions” in which pre-Revolutionary modern art was labeled “bourgeois” and “formalistic.” Soon after, works by Malevich, Tatlin, and Rodchenko were removed from museum walls and gradually erased from collective memory. Meanwhile, primarily thanks to Alfred Barr, the Russian/Soviet avant-garde was promoted and exhibited in the West and became an important part of the modern canon. However, in Russia today there seems to be a rising question of how to reclaim and reinterpret this avant-garde heritage using a different narrative, which looks for its origins perhaps not so much in Cubism and Futurism, but rather in Fedorov and Cosmism.

1:05 pm – Lunch break (1.5 hours)

2:35 pm—Session introduction

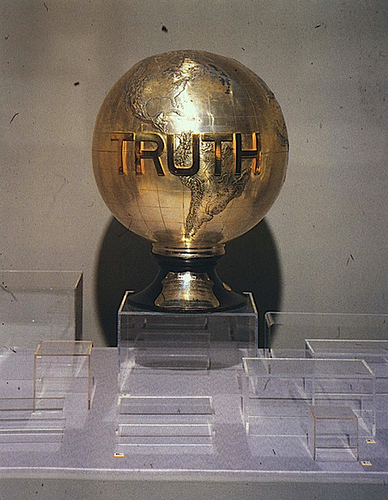

2:40 pm—Fred Wilson

Fred Wilson speaks about Mining the Museum and other museum projects that he has created over the past twenty-five years, particularly focusing on the aspects of his installations that question the orthodoxy of meaning, subvert the systems of display, and/or reveal denial within the museum. All of Wilson’s projects are inspired by observation, not premeditated intention. Projects may include ones the artist created at the Hood Museum of Art, Seattle Art Museum, Whitney Museum of American Art, Old Salem Museum, Allen Memorial Museum of Art at Oberlin College, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, and The Ian Potter Museum of Art (Melbourne), among others.

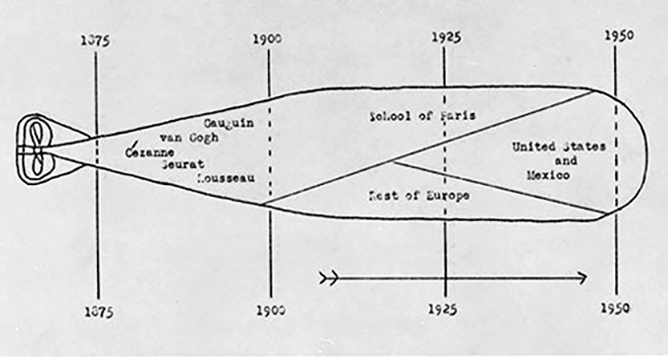

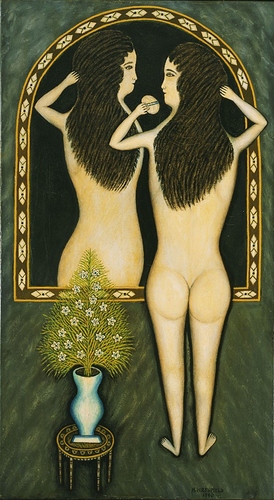

3:20 pm—Lynne Cooke

What defines whose work is shown and collected in museums of modern and contemporary art today? In the 1930s, Alfred Barr argued that the work of self-taught artists, beginning with Henri Rousseau (who had no formal academic training), constituted a tributary or division within the narratives of modern art that he was then constructing at MoMA. Recently, a number of institutions, spurred on by the example and advocacy of well-established artists, are beginning to revisit this notion—albeit in substantially revised terms.

4 pm—Kimberly Drew, “CTRL + F ‘Black’ ”

Kimberly Drew, a.k.a. @museummammy, will talk about her blog Black Contemporary Art, diversity in museums, and the role of the digital institution in 2016.

4:40 pm – Short break (30 minutes)

5:10 pm – Session introduction

5:15 pm—Irene V. Small, “Notes on the Lives of Art”

Avant-garde practices have frequently asked how art might become life. What if instead we questioned the life of art itself? This presentation considers the work of Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica, whose wearable Parangolés have long embodied a paradigm of art’s exit from the museum. Yet principles of another museum—a natural history museum where Oiticica worked while he conceived of the Parangolés—complexly condition both his own participatory proposition and the afterlives of his works. Excavating these principles suggests an alternate model of a museum: one that does not stand polemically between art and anti-art (or more crudely art and life), but functions as a space for the investigation of living things.

5:55 pm—Fionn Meade, "Objects of Prohibition"

Whether it’s Trostky’s bullet-riddled villa in Coyoacán, Mexico, Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s retreat house in Sussex, or the Nietzsche House in Sils-Maria, Switzerland, a trip to the preserved and thereby altered sites of truly significant creative production falls somewhere between the tourist cliché of encountering a time capsule and courting the uncanny. Both embarrassing and comforting to the visitor, equal parts homage and opportunism, the space of the house museum provides an uneasy model for considering the critical stagecraft of museology. By considering such examples as the Avant-Garde Institute in Warsaw (home and studio to the artists Henryk Stażewski and Edward Krasiński) and the late Decors of poet and artist Marcel Broodthaers, alongside additional contemporary artistic examples, Fionn Meade looks to the paradoxical testament of “avant house museology” for its capacity to question and disrupt the retrospective gaze.

6:35 pm—Bruce Altshuler

The e-flux publication of Soviet writings on museums reveals a largely unknown history, one in which such familiar themes as the museum-as-mausoleum and the socio-political use of institutions are presented within the framework of Marxism-Leninism. Focusing on a variety of exhibition strategies—from early twentieth-century displays in Germany, the US, and Russia, through changing postwar conceptions of the museum mission, to innovative exhibition-making in the 1990s—this talk investigates how particular museological ideas have been deployed for instrumental use in very different ideological contexts.

7:05 pm—Juliana Huxtable

Closing presentation

The event is currently at capacity; for those unable to join in person, the day’s presentations will be streaming live here

For more information on the Avant Museology symposia at the Brooklyn Museum and Walker Art Center: visit this page